By: Kevin Grace

Last week we had the pleasure of hosting an English Department lecture by visiting University of Texas professor John Rumrich on John Milton’s poetry, who spoke on the sometimes very literal connection between a physical book and an author. In the case of Milton, Professor Rumrich related the poet’s work to the curious custom that developed in the 18th century of binding books in human skin. And, in preparation for his remarks, Rumrich examined the Archives & Rare Books Library’s anthropodermic binding.

Last week we had the pleasure of hosting an English Department lecture by visiting University of Texas professor John Rumrich on John Milton’s poetry, who spoke on the sometimes very literal connection between a physical book and an author. In the case of Milton, Professor Rumrich related the poet’s work to the curious custom that developed in the 18th century of binding books in human skin. And, in preparation for his remarks, Rumrich examined the Archives & Rare Books Library’s anthropodermic binding.

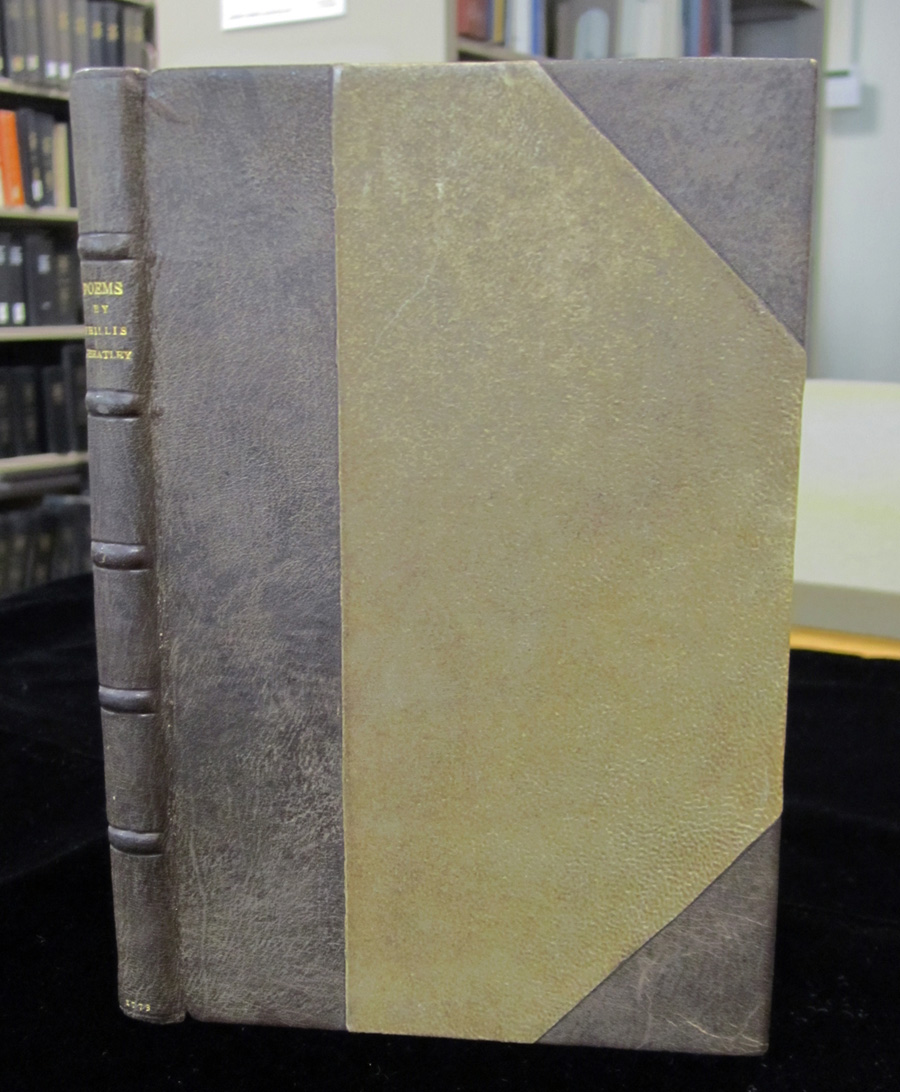

An odd volume in our holdings for over half a century, this binding encloses the poetry of Phillis Wheatley, an 18th century African American poet. Though there is no indication at all that the binding has a connection to the poet in any way, and really is an altogether other topic for discussion, it did call our attention to the Wheatley body of work, appropriate enough for a month devoted to poetry.

Phillis Wheatley was born in Africa in 1753 and sold into bondage when she was seven years old, being carried to America on the slaver, The Phillis, hence her given name. In the Boston home of the Wheatley family, she was taught to read and write and was schooled in the classics. The poetry she wrote as an adult would reflect in style and subject matter the books she was exposed to in the family library, such as the works of Milton, of Alexander Pope, of John Dryden, Virgil and Homer.

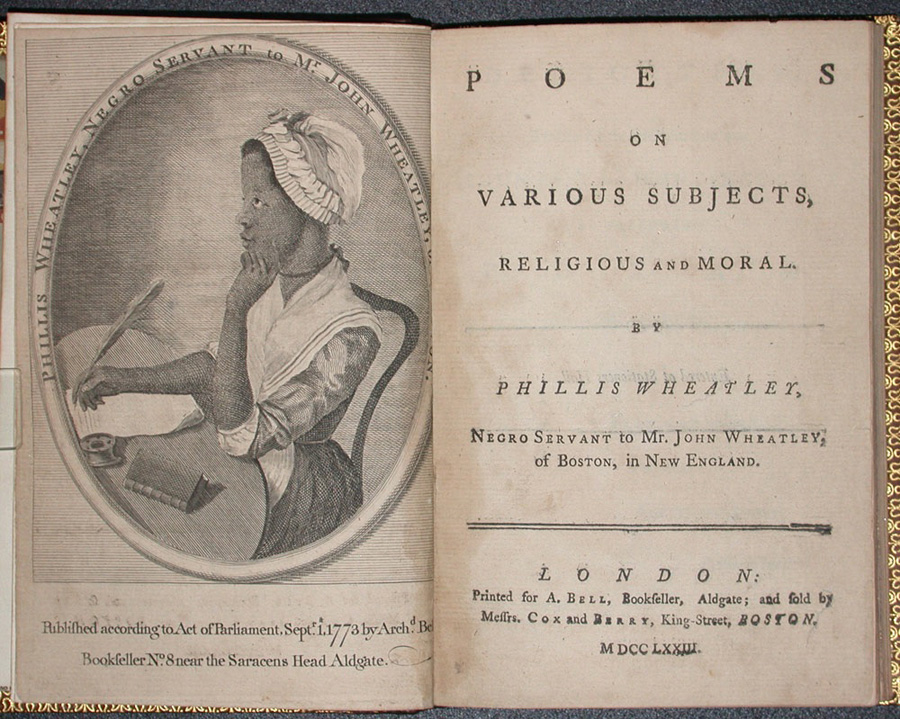

In 1773, at the age of 20, Wheatley published Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral but this appeared only after a 1772 defense in court of her earlier poems because it was speculated by many critics that a slave could not have written such elegant verse. A group consisting of John Hancock, Governor Thomas Hutchinson, Reverend Charles Chauncey, among others interviewed her at length, examined her work, and concluded that Wheatley was indeed a legitimate poet. After the publication of her volume, Wheatley achieved fame both in America and in England. The copy held by ARB was published in London and contains the famous frontispiece engraving by Scipio Moorhead. The American agents for the volume were the booksellers Cox and Berry of King Street in Boston.

Wheatley rarely wrote poetry about her own life, but in one instance, perhaps reflecting that she was still a slave in a Christian household and subject to the overwhelming influence of her master, she wrote “On being brought from Africa to America”:

‘Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

Many of her poems are elegies, written to comfort people of her acquaintance or of the Wheatley family, and others play upon themes in classical mythology. However, another touched on the African American heritage of Boston in “To S.M., a young African painter, on seeing his works”:

…For nobler themes demand a nobler strain,

And purer language on th’ ethereal plain.

Cease, gentle muse! The solemn gloom of night

Now seals the fair creation from my sight.

In 1778, with the death of John Wheatley, Phillis Wheatley was freed from slavery and shortly thereafter she married a free black man, John Peters. Peters was a grocer but as he fell into serious debt, the family was marred with tragedy through the death of two of their infant children. After Peters was sent to debtor’s prison in 1784, Phillis Wheatley worked as a maid in a boarding house. But caring for a third child who was chronically ill while at the same time doing the hard manual labor that had never been required of her in the Wheatley household, sapped her strength. She died in 1784, only 31 years old, and her son died just a few hours after her.

Though Wheatley wrote many poems after the publication of her book, they seldom saw print and then only in newspapers and pamphlets. She never published another volume of her work. In the centuries since, Phillis Wheatley has been accorded the honor of being one of our earliest African American authors, and today there is a statue representing her at the Boston Women’s Memorial.