By: Sydney Vollmer

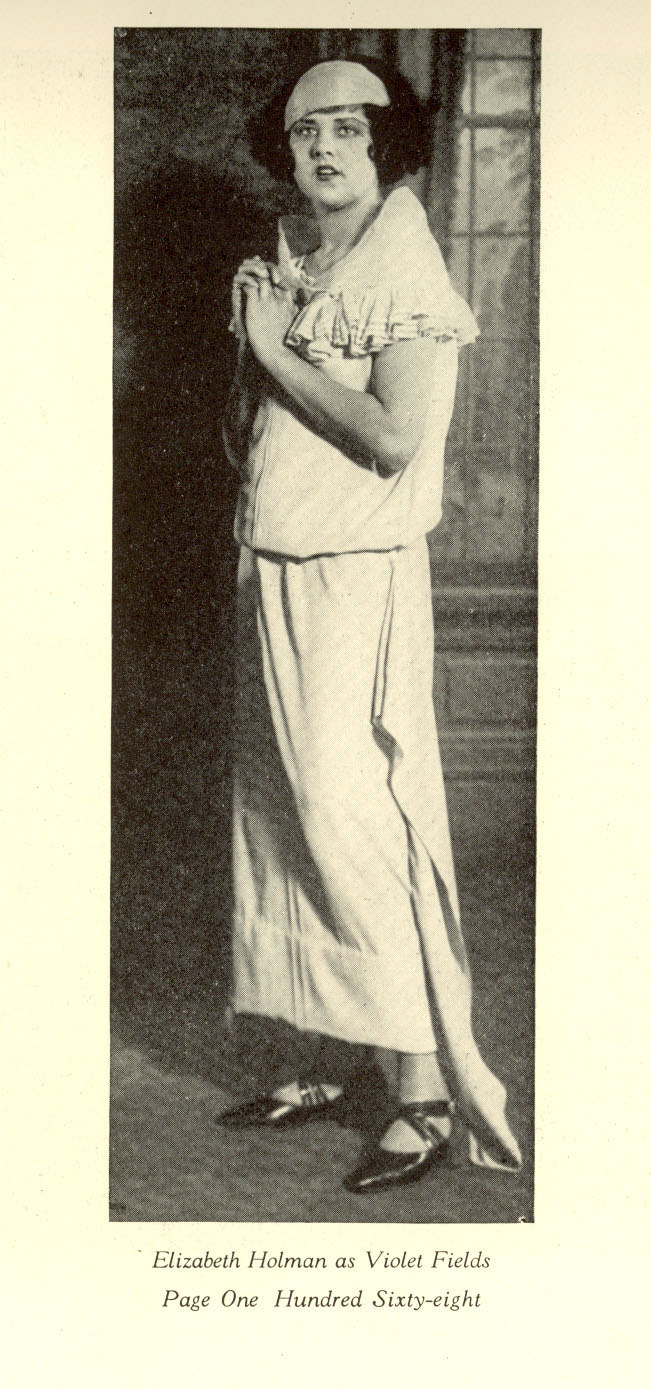

The Fresh Painters Club was considered controversial due to the type of plays it put on—nothing was off-limits. Perhaps the nature of the club was influenced by the free spirits who participated. One such spirit was Libby Holman. Nineteen Twenty-three, the year the club was founded, she played the role of Violet Fields in “Fresh Paint.” Having dreams and talent too big for her hometown, she left for New York in 1924.

The Fresh Painters Club was considered controversial due to the type of plays it put on—nothing was off-limits. Perhaps the nature of the club was influenced by the free spirits who participated. One such spirit was Libby Holman. Nineteen Twenty-three, the year the club was founded, she played the role of Violet Fields in “Fresh Paint.” Having dreams and talent too big for her hometown, she left for New York in 1924.

Born Elizabeth Holzman, her last name was changed sometime after her uncle, Ross, embezzled $1 million dollars from the stockbrokerage he owned with Libby’s father. Mr. Holzman changed the family’s name not only because of the anti-German attitudes in America at the time, but because he most likely wanted to save his kin from being attached to such an outrageous scandal, and because he needed to detach himself from the Holzman name so he could find work. This was only the first of many scandals with which Libby would be associated.

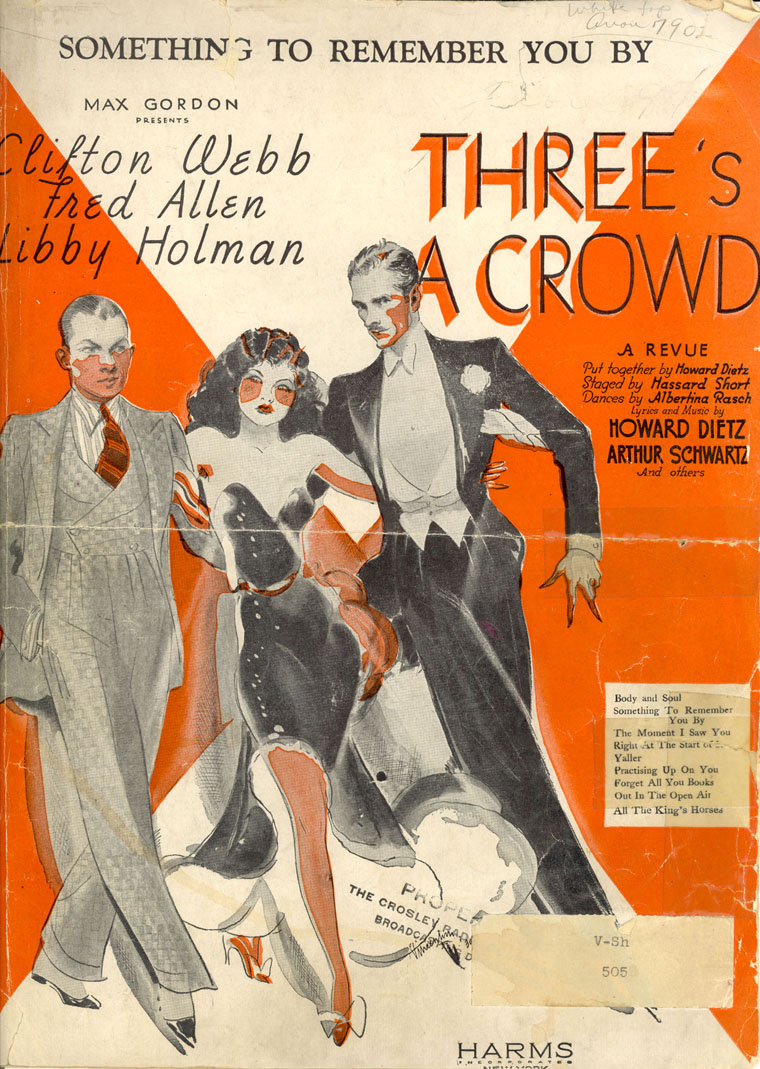

Libby attended UC from the years 1920-1923 where she studied French. Finishing her program in three years, Libby was the youngest woman of her time to graduate UC at the age of 19. Some say her dreams were to go on to law school. However, she was too young at the end of her undergraduate career. She was told her talents lay in musical theater, and was urged to move to New York. The Sapphire Ring, Libby’s first Broadway show in 1925, was a flop which only ran for thirteen shows. It wasn’t until 1929 that Libby received overwhelming accolades for a performance. During her run in The Little Show, where she appeared with Clifton Webb and Fred Allen, she sang what became her signature song, “Moanin Low.” That was her immortalizing performance, but she had other Broadway appearances as well. They included: Three’s a Crowd (1930), The Garrick Gaieties (1925), Merry-Go-Round (1927), Rainbow (1928), Ned Wayburn’s Gambols (1929), Revenge with Music (1934), and You Never Know (1938, score by Cole Porter).

Somewhere in those years an audience member fell in love with her. Zachary Smith Reynolds (who went by Smith) was the heir to the R. J. Reynolds tobacco company. For a year, he followed Holman around the world in his private plane. Apparently, stalking is endearing to some because the two were married by November 29, 1931. Unfortunately, the relationship was never a healthy one. Reynolds tried to convince Libby to leave acting all at once. Performing being her one true love, she absolutely refused. Eventually, they settled on her taking a one-year sabbatical. During that time, Libby became pregnant. She told Smith at a party at the Reynolds’ family property in July of 1932. Both were drunk and belligerent. They had an argument that led to a gunshot and Smith dying in the hospital the next day due to severe head trauma.

No one was sure exactly what had happened, but the evidence against Libby and Ab Walker (Libby’s supposed lover and Smith’s close friend) was enough that both were indicted for murder. Eventually, the Reynolds family, who had never cared for Libby or her liberal lifestyle, convinced the police to drop charges. Not wanting to be associated with a scandal, the family also persuaded the powers that be to rule the death a suicide. Unfortunately, a change in charges did nothing to quell the family’s worries about Libby raising the company’s next heir. However, Libby and her newborn son, Christopher Smith “Topper” Reynolds, benefitted greatly from the incident. Libby received a sizable settlement and Topper’s trust fund would never let him want for anything.

No one was sure exactly what had happened, but the evidence against Libby and Ab Walker (Libby’s supposed lover and Smith’s close friend) was enough that both were indicted for murder. Eventually, the Reynolds family, who had never cared for Libby or her liberal lifestyle, convinced the police to drop charges. Not wanting to be associated with a scandal, the family also persuaded the powers that be to rule the death a suicide. Unfortunately, a change in charges did nothing to quell the family’s worries about Libby raising the company’s next heir. However, Libby and her newborn son, Christopher Smith “Topper” Reynolds, benefitted greatly from the incident. Libby received a sizable settlement and Topper’s trust fund would never let him want for anything.

In 1939, Libby married an even younger man than Reynolds. Smith had been seven years her junior, but Ralph “Rafe” Holmes was twelve years younger than she. Rafe was an occasional actor and became a member of the Canadian Air Force during their marriage. Upon returning from war, the couple separated and Rafe was found dead in his New York home only a few months later. This time, suicide was a definitive ruling of the death.

With one son nearly grown, and no husband to answer to, Libby adopted two baby boys between the years 1945 and 1947 (Tim and Tony, respectively). Three years later in 1950, her biological son, Topper, died during a rock climbing trip he took with his friend on Mount Whitney. Libby never forgave herself for letting him go. She stated many times that she wouldn’t have given him permission if she had known the boys were ill-prepared for the trip. Fortunately, she took her grief and turned it into something beneficial. Libby used Topper’s death as motivation to create a memorial fund which promoted equal rights and understanding between races.

Aside from acting, civil rights was her true calling, perhaps because she was often mistaken for a mulatto woman due to her dark looks and gruff voice. She often performed with an African-American friend, folk musician Josh White. Many nightclubs had policies against letting African-Americans in through the front, let alone perform. Time and time again, Libby would put up such a stink about these policies that she refused to get on stage, convincing at least one club to change their door policy. Libby was also known for being a huge supporter of Martin Luther King Jr. (both financially and morally). After his death, she spiraled into an unmanageable depression that eventually led to suicide.

Before her untimely demise, Libby married once more. This time, she went for an older gentleman by the name of Louis Schanker. The two met while she was studying Zen Buddhism. A mutual friend introduced her to the art teacher and sculptor. He was not her type in the slightest, and her friends believed she married him solely because she wanted a companion over whom she could have power. Not very skilled or worldly, Louis never posed much of a threat to her wild personality or lifestyle—with the exception of forbidding her to see her openly gay friends, but all of her husbands had done this.

Libby was never bothered by the gay lifestyle; in fact, she embraced it. Although married three times, those were relationships of convenience—not love. Libby only had three relationships that were about love and passion, and all three were with openly gay people; two were with lesbians and one was with prominent actor, Montgomery Clift. Each of these relationships proved to be on-again, off-again. The first of these relationships was with Louisa Carpenter, a member of the wealthy DuPont family. She and Libby had a long-term relationship, but it was Louisa who eventually convinced Libby to marry Smith Reynolds. As fate would have it, Louisa was also the person to whom she turned after Smith’s death. Carpenter paid Holman’s bail and the two went into hiding together. Louisa passed away in an airplane crash in 1976 at the age of 68. Libby’s second female lover was Jane Auer Bowles who was married to openly gay author, Paul Bowles. So, when Jane and Libby met with a fiery, mutual attraction, there was no issue. The two of them lived together for years raising their children. Jane’s eventual stroke, combined with the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., led Libby into alcoholism and her eventual death.

Libby was never bothered by the gay lifestyle; in fact, she embraced it. Although married three times, those were relationships of convenience—not love. Libby only had three relationships that were about love and passion, and all three were with openly gay people; two were with lesbians and one was with prominent actor, Montgomery Clift. Each of these relationships proved to be on-again, off-again. The first of these relationships was with Louisa Carpenter, a member of the wealthy DuPont family. She and Libby had a long-term relationship, but it was Louisa who eventually convinced Libby to marry Smith Reynolds. As fate would have it, Louisa was also the person to whom she turned after Smith’s death. Carpenter paid Holman’s bail and the two went into hiding together. Louisa passed away in an airplane crash in 1976 at the age of 68. Libby’s second female lover was Jane Auer Bowles who was married to openly gay author, Paul Bowles. So, when Jane and Libby met with a fiery, mutual attraction, there was no issue. The two of them lived together for years raising their children. Jane’s eventual stroke, combined with the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., led Libby into alcoholism and her eventual death.

In 1971, Libby was found dead in her Rolls-Royce. The cause was carbon-monoxide poisoning, but a long, winding road full of turmoil, adventure, and tragedy led her there. Her two adopted sons, Tim and Tony, survived her and received $1 million each from her estate. Most of her belongings and wealth were eventually turned over to the foundation she had created in her first son’s name, the Christopher Reynolds Foundation.

To discover and use the wonderful collections in the Archives & Rare Books Library, please call us at 513.556.1959, email us at archives@ucmail.uc.edu, stop in and see us on the 8th floor of Blegen Library between 8:00 and 5:00, Monday through Friday, find us on the web at www.libraries.uc.edu/arb.html or follow us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/ArchivesRareBooksLibraryUniversityOfCincinnati/.

Sources:

http://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/holman-libby

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm2071916/bio