Uncovering a Paleontologist and Philosopher in Langsam Library

By Kevin Grace, University Archivist and Head of the Archives and Rare Books Library

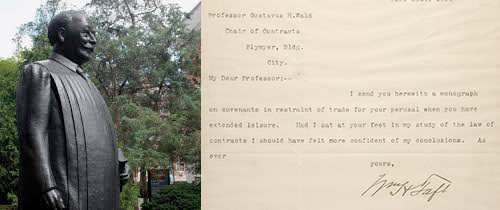

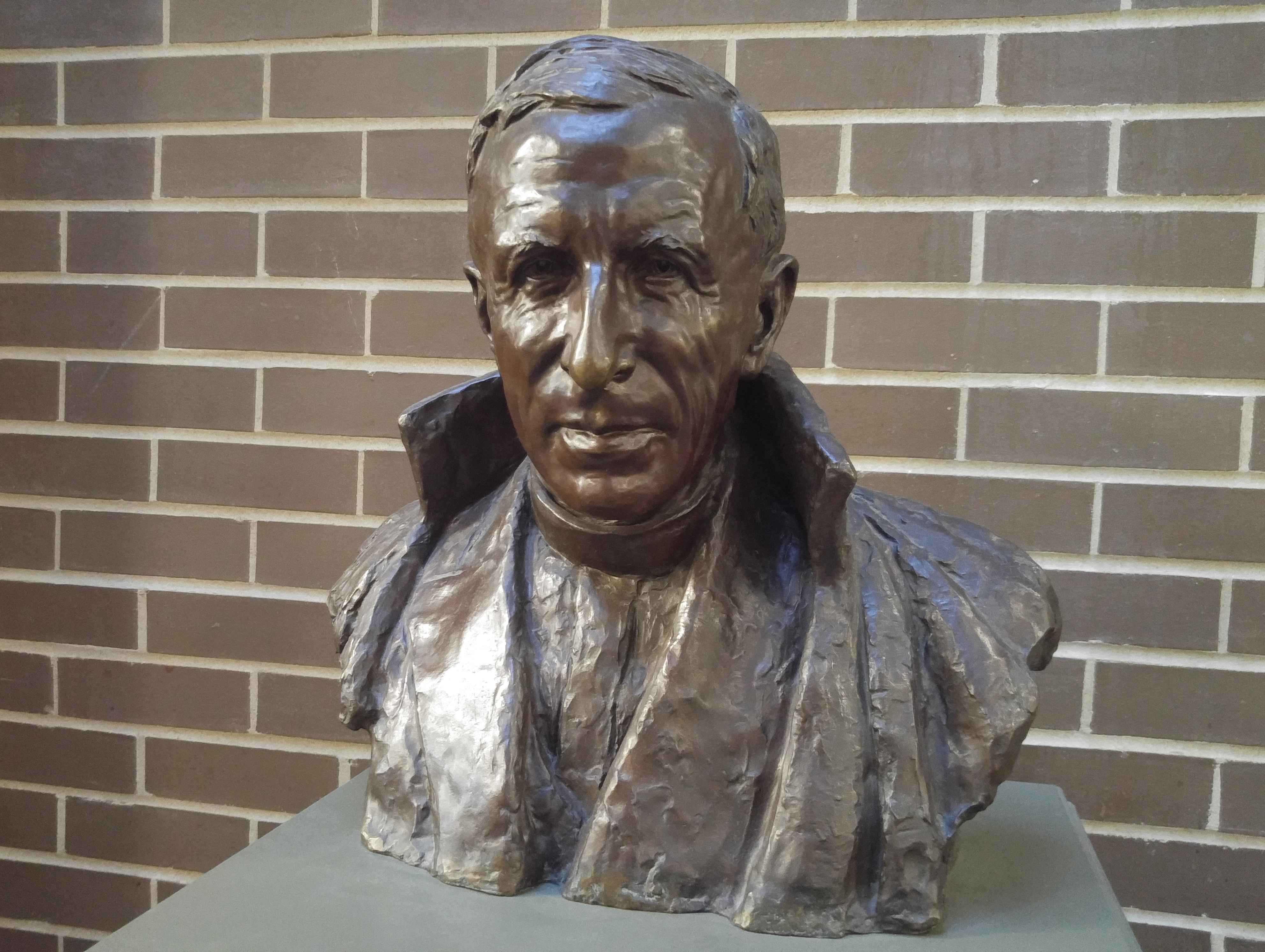

He has wandered the stacks and niches of the libraries for decades, placed here and then there by librarians and deans, wherever there was a shelf sturdy enough to hold him. In the previous Main Library (now Blegen), he took up residence in a reference room and then near the circulation desk. When the new Central Library (now called Langsam) was constructed on the north end of campus in 1978, the movers crated him up and delivered him to a new shelf on the fourth floor. And now, he is on the fifth floor in the north corridor in the space housing the Cohen Enrichment Collection. But for everyone who spots him, he is just a face. He’s been forgotten.

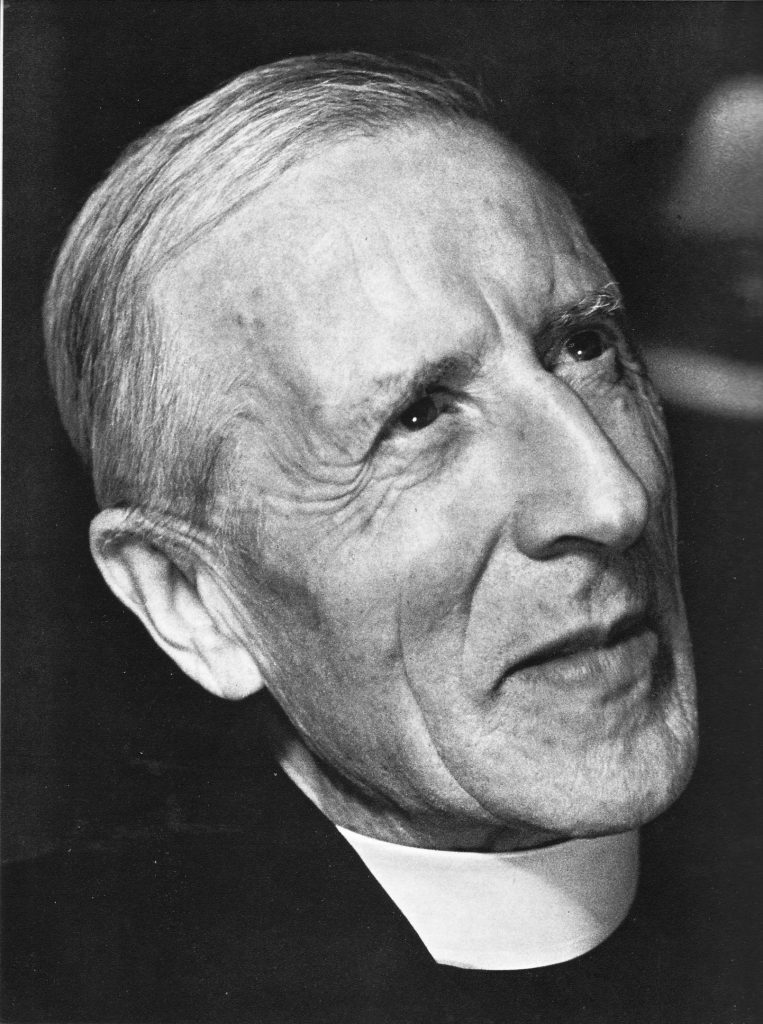

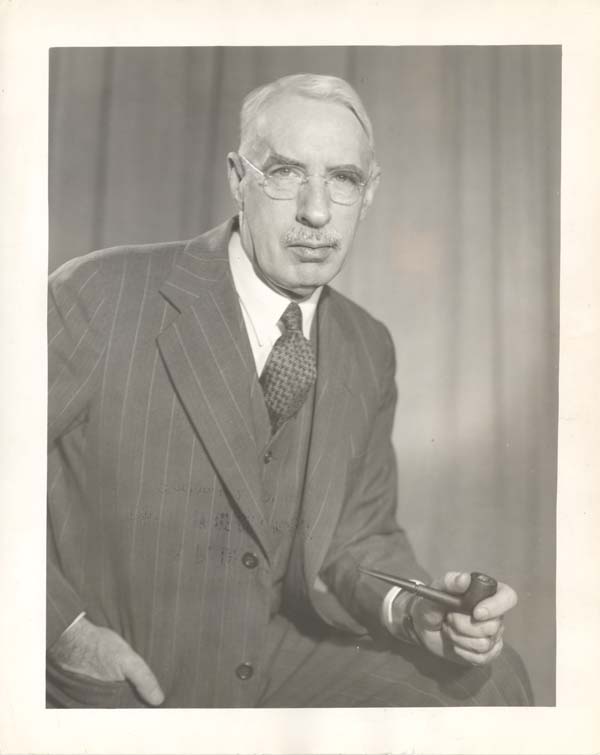

And he ought not be. “He” is a bust of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, one of the most famous paleontologists and philosophers of the 20th century. How the bust came to the University of Cincinnati is just the end of a remarkable exploration to discover the early origins of mankind. Teilhard (1881-1955) was a Jesuit priest who, in his philosophy, maintained a position on the concept of original sin that differed from that espoused by the Roman Catholic Church. After World War I, he began his geological research in Asia, and taught and lectured on spirituality and the physical reality of evolution. Because of his writings and lectures, he was censored by the Church and eventually forced to resign his teaching posts. But his work in paleontology continued, and with a team of scientists excavating sites of early human habitation in China, Teilhard determined that the discovered “Peking Man” was an early hominid, a key link in human evolution and subsequently named Homo erectus pekinensis.

One of his closest colleagues was George B. Barbour (1890-1977), a Scots geologist who served as an ambulance driver in World War I and then worked as a missionary and scientist in China where he met Teilhard. Together, the friends researched the Peking Man sites, as well as early human fossil sites in Africa, relying on each other for philosophical insights and scientific debates. Barbour was first drawn to the University of Cincinnati for a brief stay in 1932 and then after a sojourn in London, he returned to Cincinnati for good in 1937 as an associate professor. In 1938, he was named dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, a position he held until 1958 when he resumed teaching. Barbour earned an international reputation for his scientific research and his excellence as a teacher is still recognized through the annual George Barbour Award for Good Faculty-Student Relations, bestowed upon an outstanding UC faculty member.

Barbour was acutely aware of his place in global geological research, carefully documenting his career in his extensive correspondence, papers and books. He determined that his papers should be in more than one institution and a great many were donated to the Archives and Rare Books Library where they have been studied by scholars from around the world, particularly in the past few years when scholars from China have consulted them in constructing a history of geological research in their country.

And Teilhard’s bust? It is famous in its own right. Created by the eminent sculptor Malvina Hoffman (1885-1966). Hoffman had a high sense of the physical diversity of humans and often sculpted works that portrayed races and ethnicities throughout the world. She became friends with Teilhard in the 1940s, and on a commission from the French government, Hoffman created a clay model and a plaster bust of him in 1948 when she lived in Paris, delivering them to the French in 1950. Subsequently, a few bronze copies were cast, one as recently as 1963. As a close associate of Teilhard and acquainted with Hoffman, George Barbour had his own copy of the bust.

So, deep within Langsam Library there is a representation of a man who questioned the nature of heaven and earth and arrived at his own reasoning on how human beings can be an integral part of both. Along the way, he met a Scotsman, who along his own way enriched the University of Cincinnati.