The Race to Develop a Vaccine

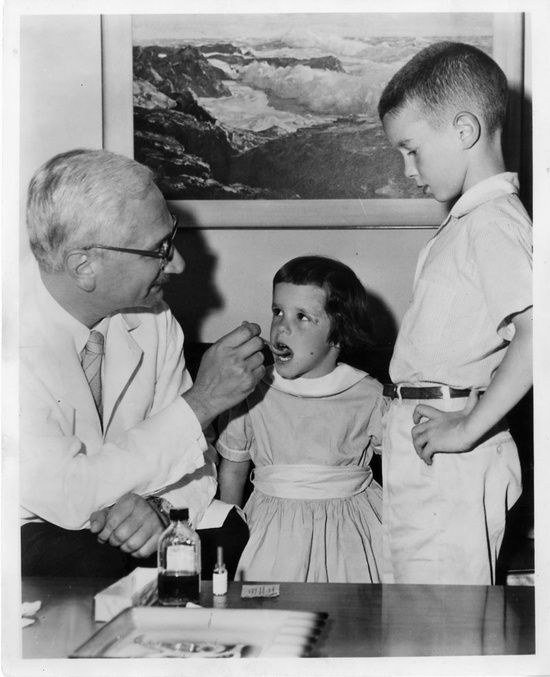

Summer was once a time of fear for many. In the 1940s and 50s, parents would keep their children inside, public pools and movie theaters would close and travelers would avoid certain areas of the United States. What brought on this panic? The threat the public feared was a virus, poliomyelitis (polio), that increased in occurrence during warmer months and would strike suddenly and within days could result in paralysis or death. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), between 1950 and 1953 there were approximately 119,000 cases of paralytic polio in the U.S. and 6,600 deaths. Even those who recovered from the initial illness often dealt with mobility and other health issues for the rest of their lives. Notably was the case of President Franklin D. Roosevelt who had difficulty walking or standing for any length of time after battling polio in 1921.

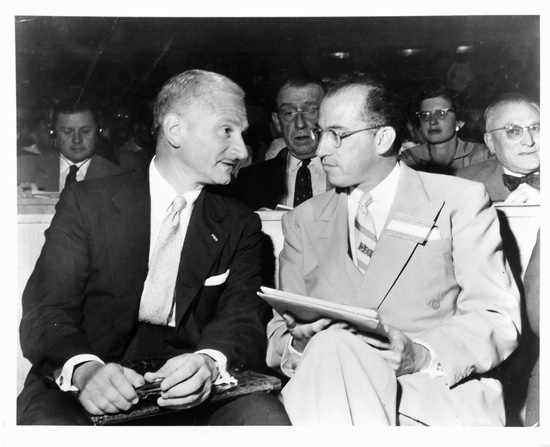

In an effort to stop the spread and devastation of this disease, scientists from all over the world worked tirelessly to study the virus in efforts to develop a vaccine. First to achieve success was Dr. Jonas Salk, whose injected vaccine composed of “killed” polio virus was made available in 1955.

Dr. Albert B. Sabin, distinguished service professor of research pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and fellow of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation, would soon follow in the early 1960s with the world’s first oral live-virus vaccine to be used in the battle against poliomyelitis. Much more effective and economical to produce, and easier to administer on a sugar cube, the “Sabin Vaccine” soon became the world’s weapon against polio and played a key role in eliminating the virus from most of the world.

Upon Dr. Sabin’s death in 1993, his wife Heloisa donated to the University of Cincinnati 400 feet of Dr. Sabin’s correspondence, laboratory materials, manuscripts, awards, medals and numerous other documents pertaining to his career and medical research. His papers record both the development and testing of the oral polio vaccine, and the growth of virology as a discipline.

In 1995, the John Hauck Foundation helped the Cincinnati Medical Heritage Center (now the Henry R. Winkler Center for the History of the Health Professions) establish the Hauck Center for the Albert B. Sabin Archives. An initial gift provided funds for an archivist to organize and preserve Dr. Sabin’s collection. Later, the Hauck Foundation provided the Winkler Center with two additional donations that helped with the construction of the Winkler Center’s new home and the building of the John Hauck Foundation Gallery in the space.

In 2019, selections of the Albert B. Sabin Papers Laboratory Notebooks were digitized with another gift from the John Hauck Foundation. The digitized materials were added to UC’s online repository, Scholar@UC (search “Sabin Notebooks”). The physical collection of laboratory notebooks holds the entirety of Sabin’s laboratory work during his time at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation and the University of Cincinnati (1935 to 1969), including his service during World War II.

The Winkler Center created an online exhibit for those who want to learn more about the work and impact of Albert Sabin. Included on the site are a biography and timeline, a rich archive of Sabin’s professional papers that include correspondence, military service documents, books, photographs, research slides and notebooks on poliomyelitis and other diseases. Also included are awards Sabin received, information about his academic history and published works, and much more.

Researching this collection one is struck by the parallels between the work done to rid the world of a dangerous virus both then and now. Gino Pasi, archivist and curator of the Sabin Papers, noted that Sabin’s collection has always been “heavily used and researched by scholars from across the world, but over the last year, the number of requests for this collection has skyrocketed, especially as it relates not only to the development of vaccines, but also to the logistical details of mass vaccinations.”