In August 2011, I attended the Society of American Archivists annual meeting in Chicago, Illinois. While there, I attended a session called “Exploring the Evolution of Access: Classified, Privacy, and Proprietary Restrictions.” As I sat in the room listening to the speakers, I started to think how to apply these concepts to the Sabin digitization project.

For several weeks after the meeting, my colleagues and I had lively debates about how these concepts, as well as the recent SAA endorsed “Well-intentioned Practice for Putting Digitized Collections of Unpublished Materials Online” document, would affect the display of the Sabin materials online. On one hand, we recognize that Mrs. Sabin left Dr. Sabin’s important collection in our hands to ensure that this material is accessible to researchers around the world. On the other hand, we also recognized the need to do two things: 1.) protect the health information of those mentioned in the collection that participated in Dr. Sabin’s research, and 2.) make sure we don’t leak any classified government information online. Even though much of Dr. Sabin’s materials related to his research and his work with the military are considered “old” by some standards, it is still necessary to do our due diligence to protect information as needed.

In order to do this, we are in the process of examining letters, beginning with the Military Service series, for information that may need to be redacted. While doing this analysis, I have learned many interesting things about Dr. Sabin and his military service. I want to share some letters that I have come across during this process.

One of the diseases Dr. Sabin did considerable research on while serving his country is dengue. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, dengue is a viral disease that is transmitted by mosquitoes, including the Aedes aegypti. It causes high fever, severe headache, severe pain behind the eyes, joint pain, muscle and bone pain, rash, and mild bleeding. It also can cause death in some cases. Outbreaks of dengue typically occur in tropical urban areas around the world. In the 1940’s, dengue was seen as a military problem because of the increased amount of soldiers traveling to tropical areas. Dr. Sabin and his colleagues on the Commission on Neurotropic Virus Diseases worked to try to develop a vaccine for dengue.

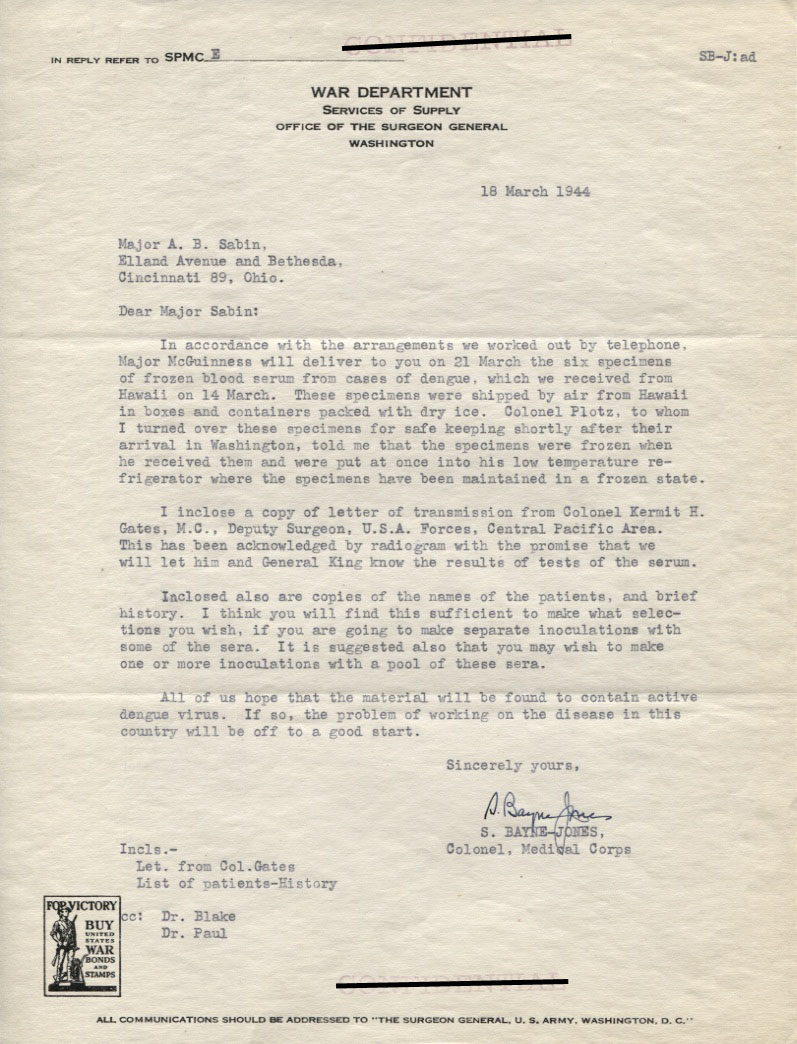

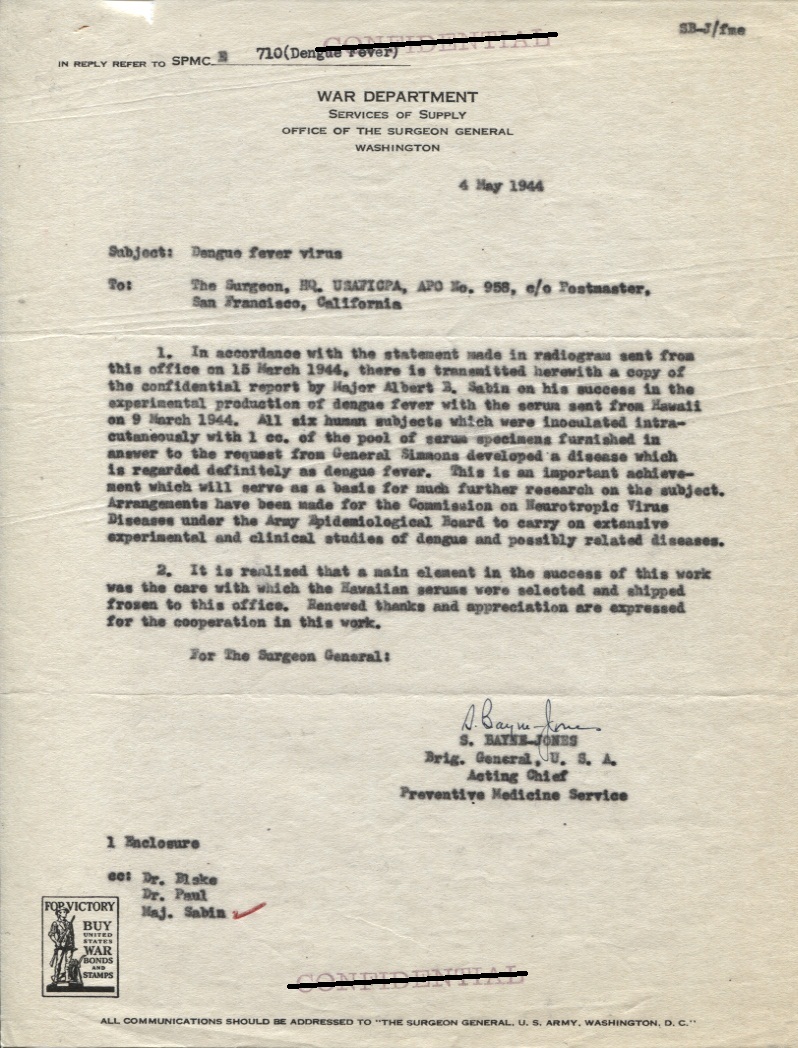

The first letter (seen above) is a letter from Colonel Stanhope Bayne-Jones to Dr. Sabin. They discuss sending frozen blood serum from several dengue cases in Hawaii. (It amazes me how they could send this type of material through the mail back then!) Colonel Bayne-Jones wrote, “All of us hope that the material will be found to contain active dengue virus. If so, the problem of working on the disease in this country will be off to a good start.” The next document (seen to the right) was sent just a few months later. This is a memo regarding Dr. Sabin’s successful production of dengue fever with a serum sent from Hawaii. Bayne-Jones, who was promoted to Brigadier General, wrote that the production of dengue fever through Dr. Sabin’s research was “an important achievement which will serve as a basis for much further research on the subject.”*

At the time, these letters were marked “Confidential” by the War Department. Our collection holds several letters with this classification stamped on it, as well as the classification “Restricted.” After attending the SAA session, I learned that we couldn’t just assume that because a document was almost 70 years old that it wasn’t still considered classified. By contacting the National Archives and Records Administration’s Information Security Oversight Office, I learned that the “Restricted” classification is no longer used and therefore not considered classified. The “Confidential” letters are a little more tricky and require more investigation. A 2010 document on classification from the NARA says, “’Confidential’ shall be applied to information, the unauthorized disclosure of which reasonably could be expected to cause damage to the national security that the original classification authority is able to identify or describe.” Do the Sabin letters seen here fall into that category that they still should be classified?

After communicating with the ISOO, it was determined that information contained in these letters, and others from the World War II era related to Army epidemiology and related research, is not considered classified. We will indicate that the document is no longer classified by striking through the classification stamp (as seen here with “Confidential”) and adding a note in the metadata that says the ISOO considers this information declassified. When we come across more information marked as “Restricted” or “Confidential,” we will follow the same procedure that we have established here, in order to ensure the material we have is not classified.

With regard to dengue, over 60 years after Dr. Sabin was able to produce dengue fever through his research, there is still not a vaccine for the prevention of the disease. According to the Sabin Vaccine Institute, there are almost 50 million annual cases of dengue today. Hopefully experimental vaccines, which are currently in clinical trials stages, will be available soon to stop the spread of this disease.

*These letters can be found in Series #5 – Military Service, Sub-Series Dengue, Box #12, Folder #7 – Hawaiian Serum Specimens, 1944-1950.

In 2010, the University of Cincinnati Libraries received a $314,258 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to digitize the correspondence and photographs of Dr. Albert B. Sabin. This digitization project has been designated a NEH “We the People” project, an initiative to encourage and strengthen the teaching, study, and understanding of American history and culture through the support of projects that explore significant events and themes in our nation’s history and culture and that advance knowledge of the principles that define America. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this blog do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.