This two-part exhibition commemorates the 145th anniversary of the invention of the telephone (1876) that took place in 2021; COVID-19 slightly delayed the celebration. Displayed on the 4th floor lobby of the Walter C. Langsam Library are reproductions of 68 vibrant, chromolithographic covers of illustrated sheet music dating from 1877 to 1939.

The display outside and inside the Robert A. Deshon and Karl J. Schlachter Library for Design, Architecture, Art & Planning (DAAP) features two dozen original pieces of sheet music, along with ten vintage telephones. The name of the device, from the Greek, means “far speaking” a way of increasing human earshot. With it, people can make themselves heard and understood around the world with a whisper.

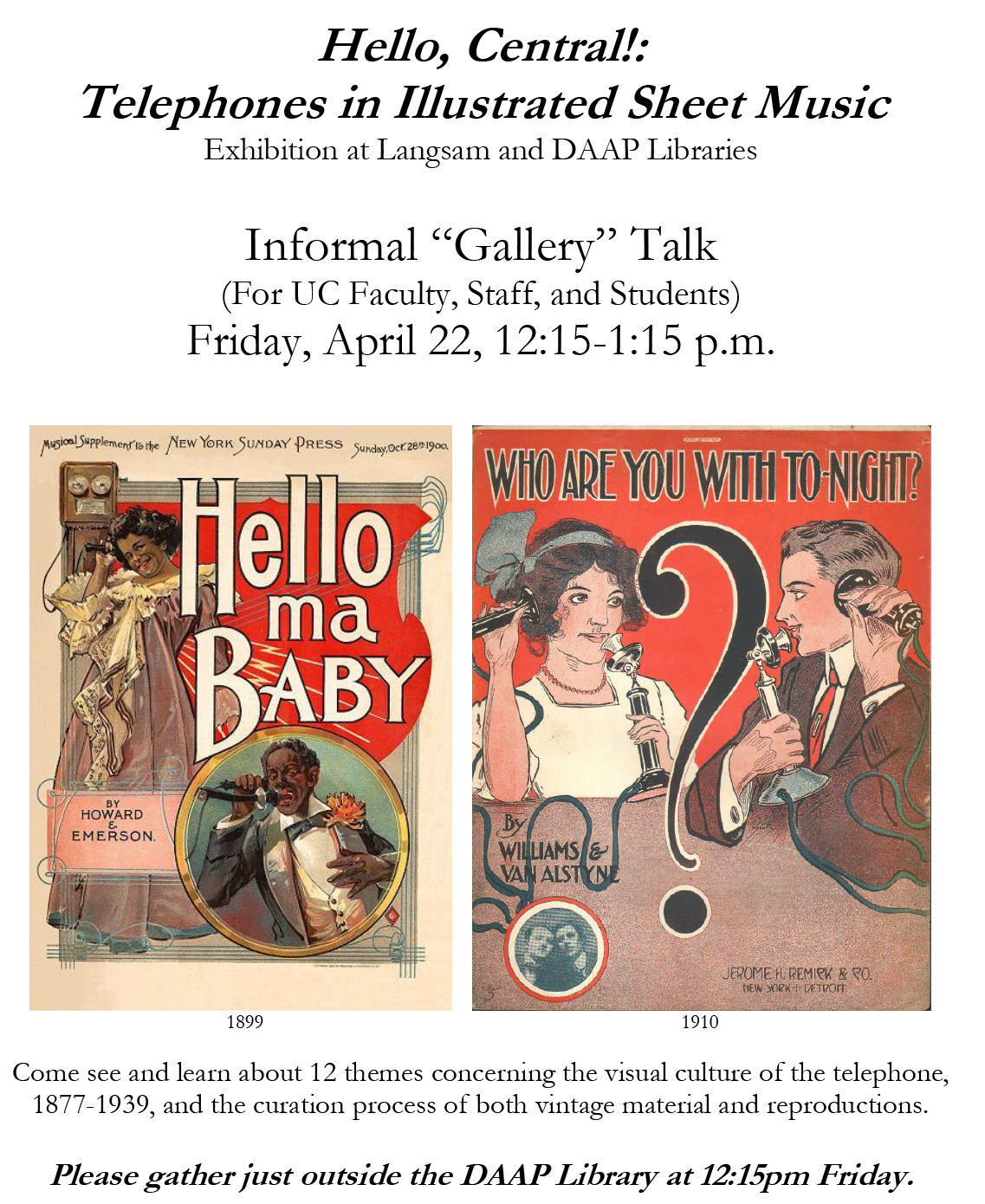

So wondrous was the new technology of Alexander Graham Bell’s invention (thought to be the most valuable patent ever issued) that it inspired over 650 songs about the telephone before 1937, and it was equally popular in plays and prose. The workings of a clock, bicycle, or train were visible and relatively easy to understand. However, it seemed incredible to contact somebody miles away almost instantaneously via a completely invisible force.

Modern inventions of space-transcending technologies—such as the telegraph, telephone, bicycle, and automobile before World War I—liberated and empowered average Americans, creating an extended present of simultaneity. As an essentially democratic device, the telephone carried everyone’s voices (children included) with equal speed and directness. Although there was a wide range of reactions to early telephony, from wonder to distaste, most people embraced it as a technical and social tool that they used in daily life.

The first phones in 19th-century towns appeared at the railroad station, the druggist, a major landowner’s home, or the sawmill, and were connected by copper wire to a central switchboard in a larger town. Perhaps surprisingly, farmers had more telephones than urban people before the mid-1920s because the tool was useful for emergencies (e.g., accidents, tornadoes, floods) and helped reduced loneliness and insecurity in rural areas. However, after 1920, higher rates, disinterest from commercial companies, and tough economic times led to a decline in rural telephone use in favor of automobile purchases. Nevertheless, national use expanded rapidly. By 1950, 62% of American homes had telephones. Today, cell phones are ubiquitous–5.13 billion people (66.5% of the world’s population) own mobile devices.

Before the widespread use of phonographs (beginning in the late 1890s) and radio (the first broadcast radio news program was in 1920), music performance at home and at social functions was a major form of social popular culture. Publishers made enormous profits selling tens and hundreds of thousands of single compositions. Between 1900 and 1910, over 100 songs sold more than a million copies. “Let Me Call You Sweetheart” (1910) sold eight million. The U.S. population was just over ninety-two million that year. That means that almost every twelfth person owned a copy of this piece of ephemera. Such ubiquity underscores the tremendous impact of sheet on United States society historically, and a good number of early compositions are still familiar and sung today.

Middle-class patrons avidly purchased sheet music to sing songs and play compositions on home pianos as a widespread form of entertainment, and they displayed the large compositions (with a standardized size of 14” x 11” before World War I and 12” x 9” afterward) in parlors. They savored sentimental ballads and jaunty tunes (early ragtime, jazz, and Tin Pan Alley melodies) with eye-catching covers commissioned specifically for the music, most of it from freelance artists, some of whose names are lost. Today, collectors avidly seek the work of such talented sheet music illustrators as Albert Wilfred Barbelle, John Frew, Edgar Keller, Frederick Manning, Irving Politzer, John V. Ranck, Morris Rosenbaum, Frederick and William Starmer, André De Takacs, Solomon Wohlman, and Helen Van Doorn Morgan.

All of these compositions underscore the pivotal roles that telephones play in human relationships, with an emphasis on romance. In Understanding Media (1964), Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan wrote, “the telephone demands complete participation,,,[it] demands a partner, with all the intensity of electric polarity.”

Curated by Theresa Leininger-Miller, professor, Art History, School of Art/College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning

Acknowledgments for Hello, Central! Telephones in Illustrated Sheet Music

This exhibition would not have been possible without assistance from the following people (in alphabetical order by last name):

Stephanie Bandel, David Butler, “Perfessor Bill” William G. Edwards, Vince Giordano, Alex Hassan, Lucille Jordan, Carrie P. Mastley, Elizabeth Meyer, Brian Miller, Melissa Cox Norris, Terry Parrish, Christopher Platts, Natalie Rogers, and Monica Williams-Mitchell.

With special thanks to Lucille Jordan who provided research assistance and transcribed dozens of song lyrics in the summer of 2020 through UC’s Honors Discover Program and to Elizabeth Meyer, Monica William-Mitchell, and Daniel Vogt, D.D.S. who generously lent vintage telephones from their private collections.

And join us Friday, April 22, 12:15pm outside the DAAP Library for an informal gallery talk…