William A. Procter and the Gift of Libraries

By Kevin Grace, Head of the Archives and Rare Books Library

As the University of Cincinnati heads into the final months of celebrating its bicentennial in 2019, there are a few significant aspects of this 200th birthday that are hereby decided. For example, the 1819 founding of the Cincinnati College versus the 1870 establishment of UC is officially settled: “The University of Cincinnati, est. 1819” is carved on our intellectual cornerstone. Bicentennial publications say so, decades of Bearcat administrators claiming it back it up, and that early date looked great on birthday cupcakes. Another affirmation of the university’s 200-year heritage is that we learn both by new endeavors and by past experiences. The fresh innovations can be exhilarating and the history can be painful but by taking them together, the path forward should be well-illuminated.

And while pushing ourselves to a strong global engagement, we remembered that we began on the streets and hillsides of Cincinnati. We are a university of the world with a base in the local community. That, in fact, is how our libraries began at the University of Cincinnati. In the days of the Cincinnati College, students provided their own books (with occasional inspections of living quarters by faculty to make sure the students weren’t tucking away any unseemly literature) or they used the public library.

Founded in 1828, the Ohio Mechanics Institute, which by its evolutionary direction is now part of the College of Engineering and Applied Science, established a library built primarily on the gifts from Cincinnati industrialists who toured Europe and donated the books they purchased. OMI’s students also used the public library. But when the University of Cincinnati was firmly established in 1870, there was no general campus library established with it. Even after the first university building was constructed in 1875 on the old McMicken property along lower Clifton Avenue, academic departments held a shelf or two particular to their disciplines but student access to books was mixed at best.

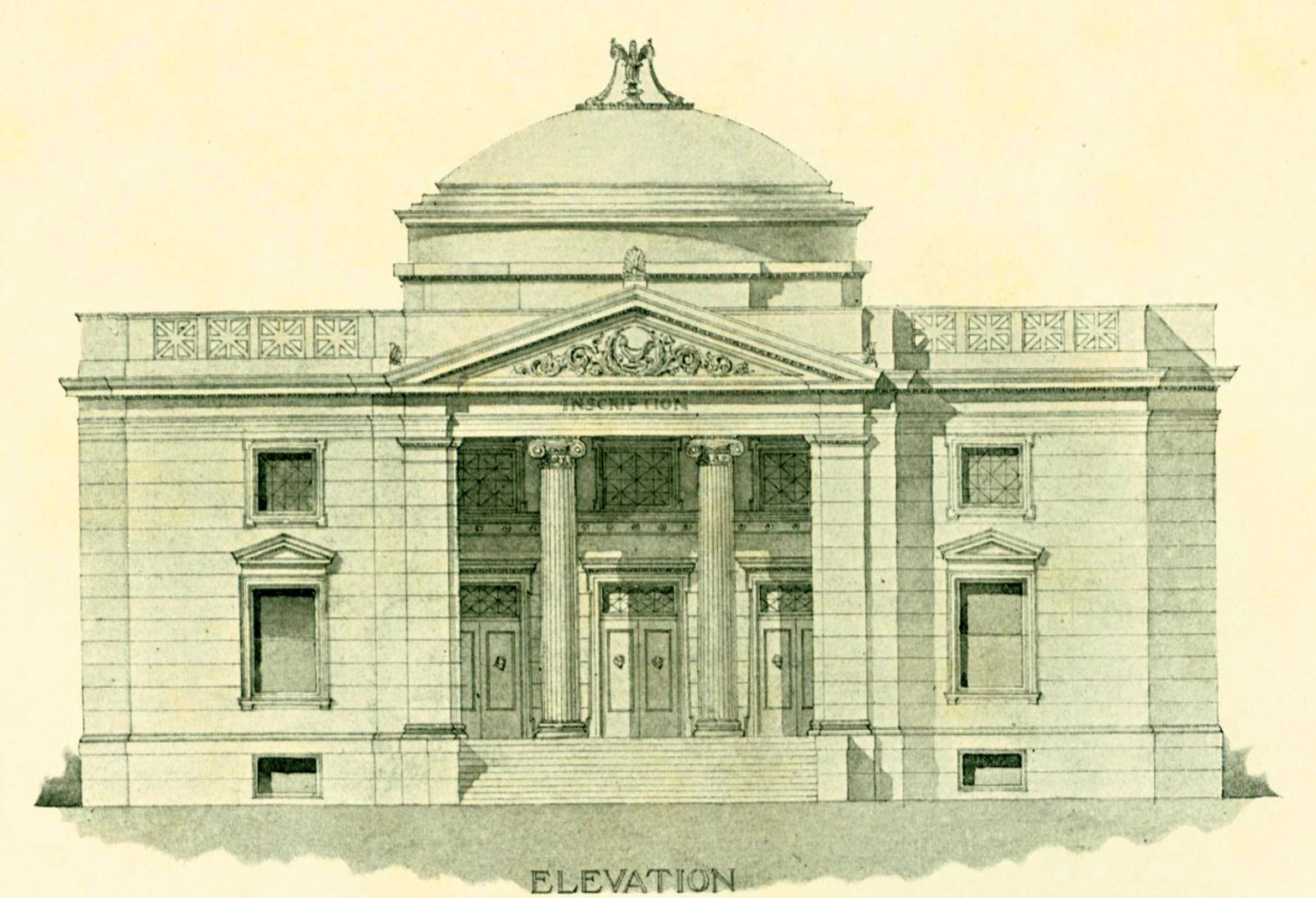

It wasn’t until after the university moved to Burnet Woods in 1895 that there was any movement to actually creating a library along with the buildings along the academic ridge. McMicken Hall with its wings of Cunningham and Hanna Halls was designed by the renowned architectural firm of Samuel Hannaford & Sons, and with the gift of Asa and Julia Van Wormer, Hannaford would design a separate library building, distinct from classrooms and faculty studies. Van Wormer Library opened in 1899, constructed for $64,000 dollars and boasting a nice dome to set it off. But how to fill it? That’s where UC’s place as a university of the city, as an institution of higher learning tied to its neighbors and the citizens of Cincinnati, became fruitful. In 1898 as the Van Wormer Library was constructed, William A. Procter stepped forward with the first of three gifts that formed the nucleus of a University of Cincinnati library.

The son of the co-founder of Procter & Gamble, William A. had a strong predilection for books. He was a graduate of Kenyon College and eventually he would step into the leadership of the family firm, creating research laboratories and extending its products to consumers worldwide. But before that, even after working occasionally for his father as a young man, William A. Procter was employed by the Robert Clarke Publishing Company. Clarke’s firm not only published books but operated as a bookseller as well. Procter was exposed to all aspects of the book trade under Clarke and recognized the absolute importance of a library. So after he became president of Procter & Gamble in 1890, built upon his love of books by purchasing Clarke’s private library shortly before the bookman’s death in 1899. Clarke was a strong collector of Americana, geography, history, and travel and his collection consisted of 6,574 volumes. By this time, Procter was a member of the university’s board of directors, as they were called when UC was a municipal university, and he made known his intention to donate the library after construction was completed on the library building. There would be more.

Procter purchased part of the library of Cincinnati businessman Enoch T. Carson, who died in 1899. The bulk of Carson’s library consisted of Masonic volumes, tens of thousands of them, and those were sold at auction. Procter’s purchase was of Carson’s Shakespeariana collection, nearly 1500 volumes. After Procter bought the books, he also had in hand Carson’s extensive collection of prints and engravings relating to Shakespeare’s plays, most of them from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. What to do with them? Procter took one complete set of Shakespeare volumes in the Carson library, the 1849 Charles Knight edition, had it disbound and then rebound with the engravings tipped in. It became what is termed as an “extra-illustrated” edition making it, in effect, a unique collection of books.

Procter gave even more. He also purchased the chemistry library of Professor Timothy Herbert Norton and donated that to the University of Cincinnati as well, 992 volumes. These three private libraries formed the basis of the University of Cincinnati’s library collections today, and the books are still in use. The Carson Shakespeare volumes are part of the Archives & Rare Books Library, as is the Clarke collection. Both have been greatly augmented over the decades with more purchases of rare materials in their relative subject areas. Likewise, the Norton chemistry books in the Chemistry-Biology Library at UC. William A. Procter served on the board at UC until 1906, shortly before his death. Today the libraries at the University of Cincinnati number well over 4 million titles and in the university’s bicentennial year, they represent the shared heritage with its city and its citizens as well as the cornerstone for an innovative global library.