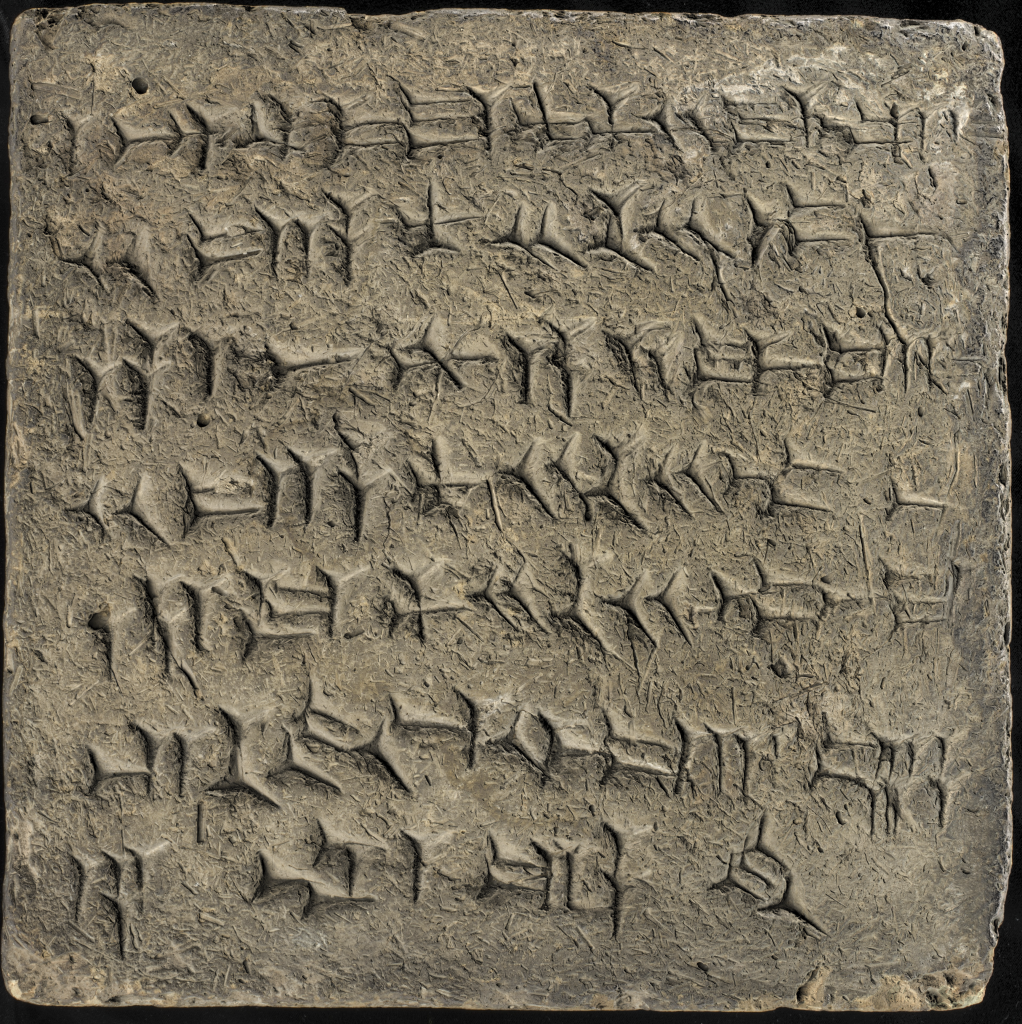

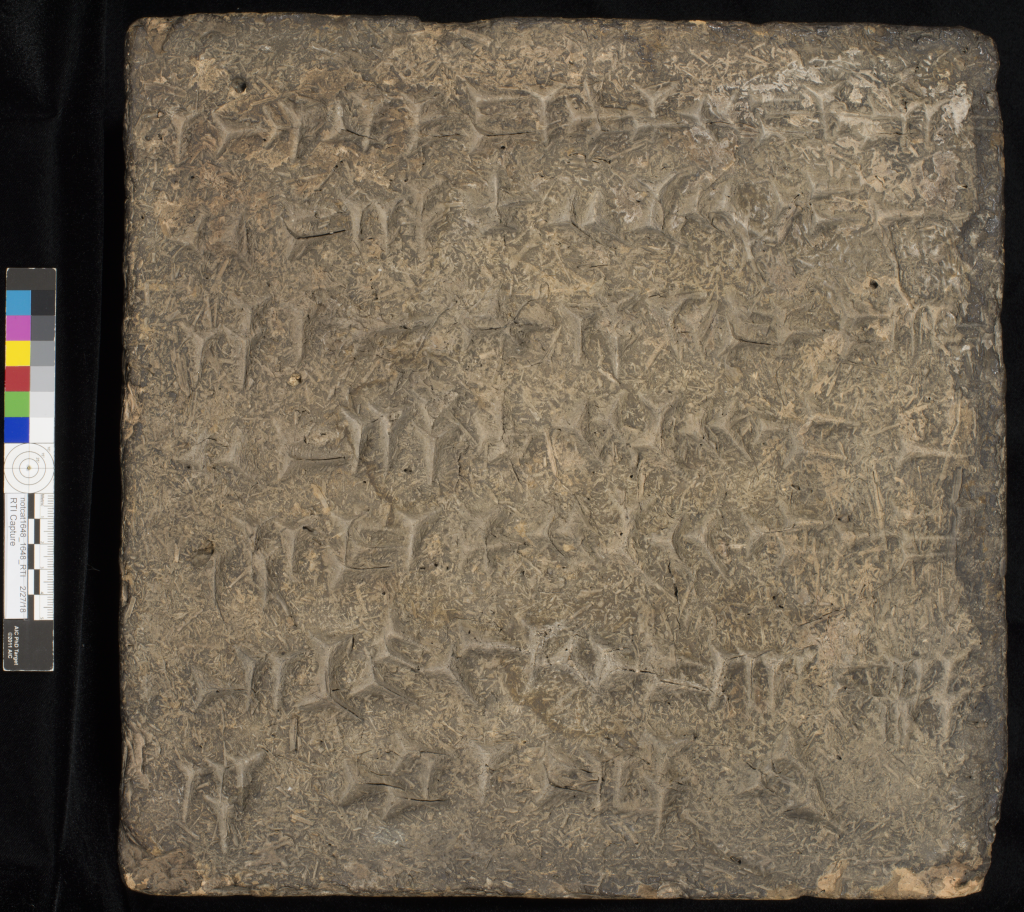

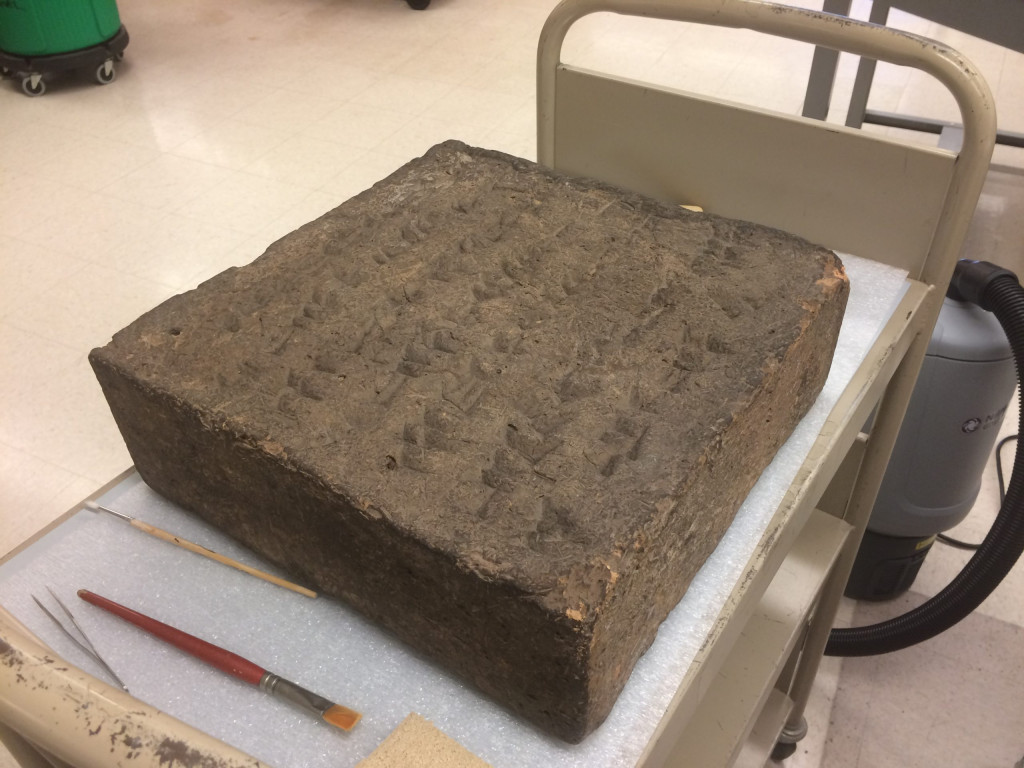

The University of Cincinnati’s Archives and Rare Books Library owns a few cuneiform tablets that date around the 1st century BCE. Most are small enough to fit within the palm of your hand. However, the clay tablet in question measures 14 inches (W) by 14 inches (T) x 4.5 inches (D) and weighs roughly 40-50 lbs.

More accurately, it is thought to be an Assyrian cornerstone that dates between 860 and 824 BCE. It is described in the catalog record to be from the ruins of Calah (near Ninevah) on the Tigris River. It is likely the cornerstone of a temple or palace erected by Salmanser III, king of Assyria. The provenance of how the University acquired the tablet is uncertain.

A translation of the cuneiform writing reads, ““Salmaneser, the great king, the mighty king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, son of Asurnaserpal, the great king, the mighty king, the king of Assyria, son of Tukulbi-Ninib, king of the universe, king of Assyria, and indeed builder of the temple-tower of the city of Calah.”

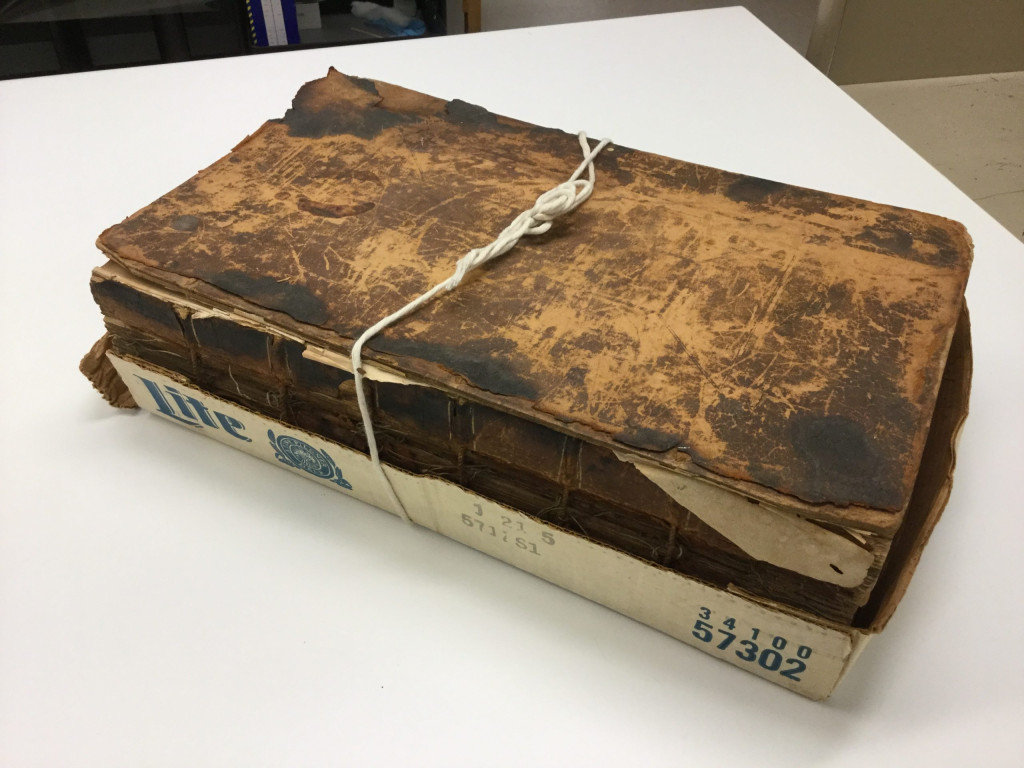

After surface cleaning and digitizing the cornerstone, finding suitable storage for an Assyrian cornerstone tablet seemed like a straightforward task in the beginning. I thought, “Let’s get it off the floor, house it, and protect it from dust!” No problem, right?

But once we got the item back in the lab, the weight of the object combined with its fragility proved more of a challenge after Chris, Holly and I began thinking about how the object would be retrieved from storage and how it would be handled. Rather than being stored in specialty shelving (such as items might be in a museum), this item was a library item. We needed to fit the tablet amongst archival book shelving. We were also faced with the prospect of transporting the cornerstone up and down a flight of stairs from the secure rare book storage. There is no easy elevator access! And finally, once it was put in an enclosure, how would a librarian get it out to show researchers and students?

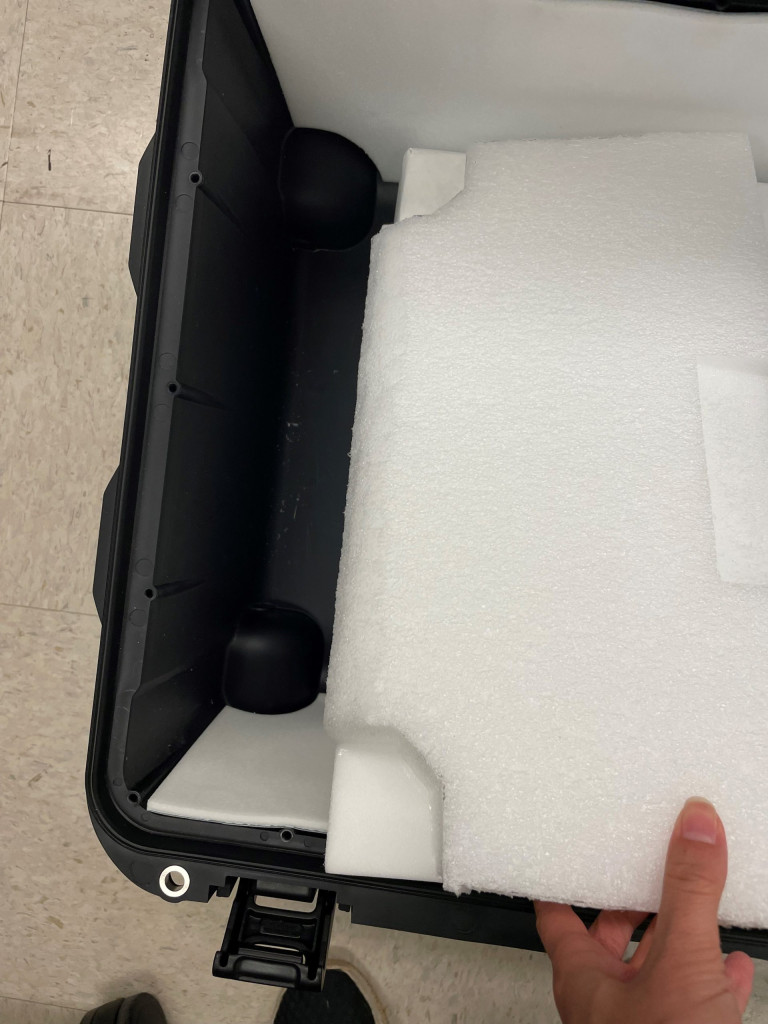

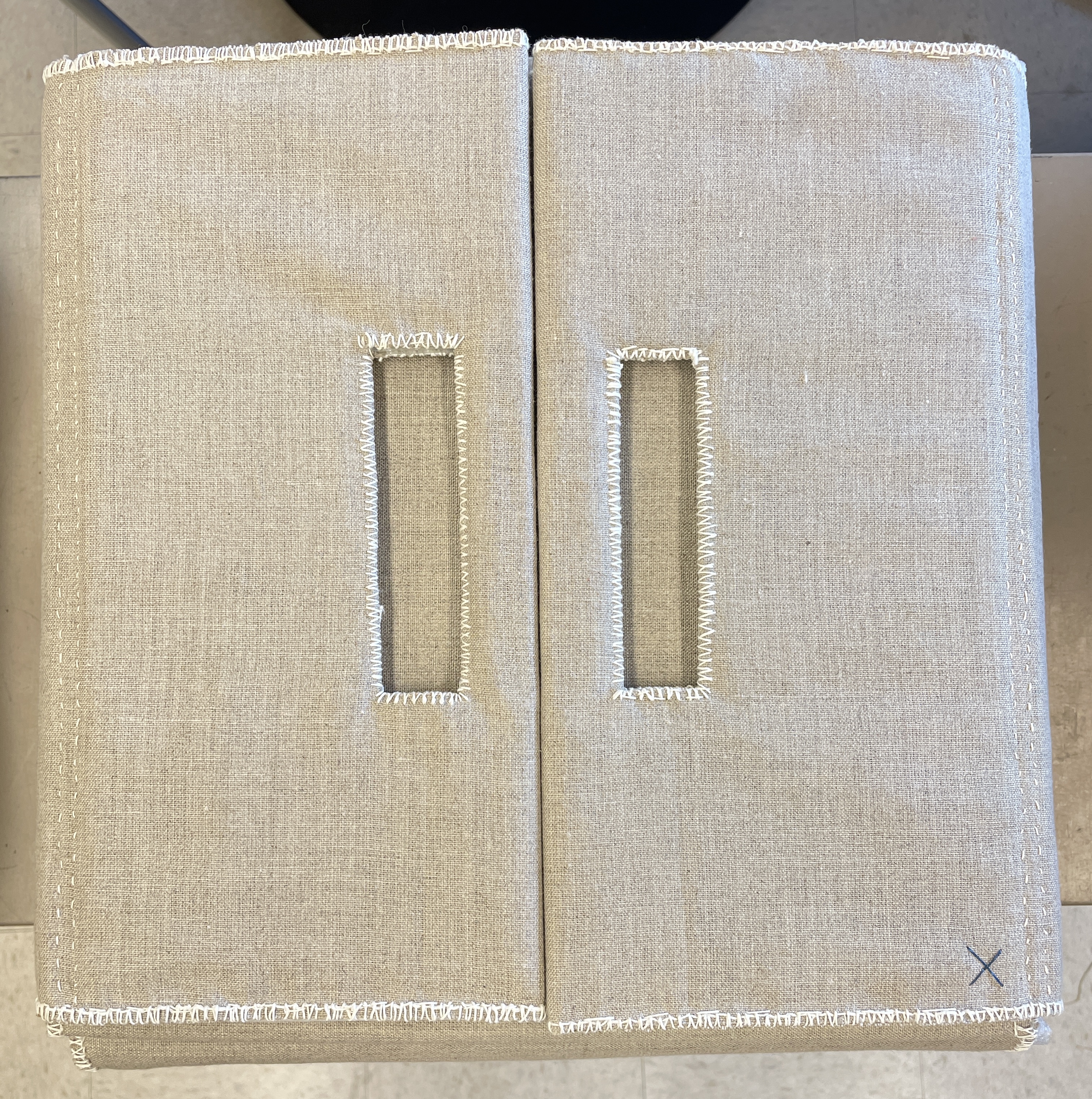

We decided on an industrial case with wheels that could be transported and stored anywhere. I knew I wanted a device with handles to pull the object in and out of the case, but immediately decided against the idea of ratchet straps. The threat of fracturing would be too great if the ratchet straps were over-tightened.

After careful thought (and the creation of mock up solutions!) the following custom design was created in five stages:

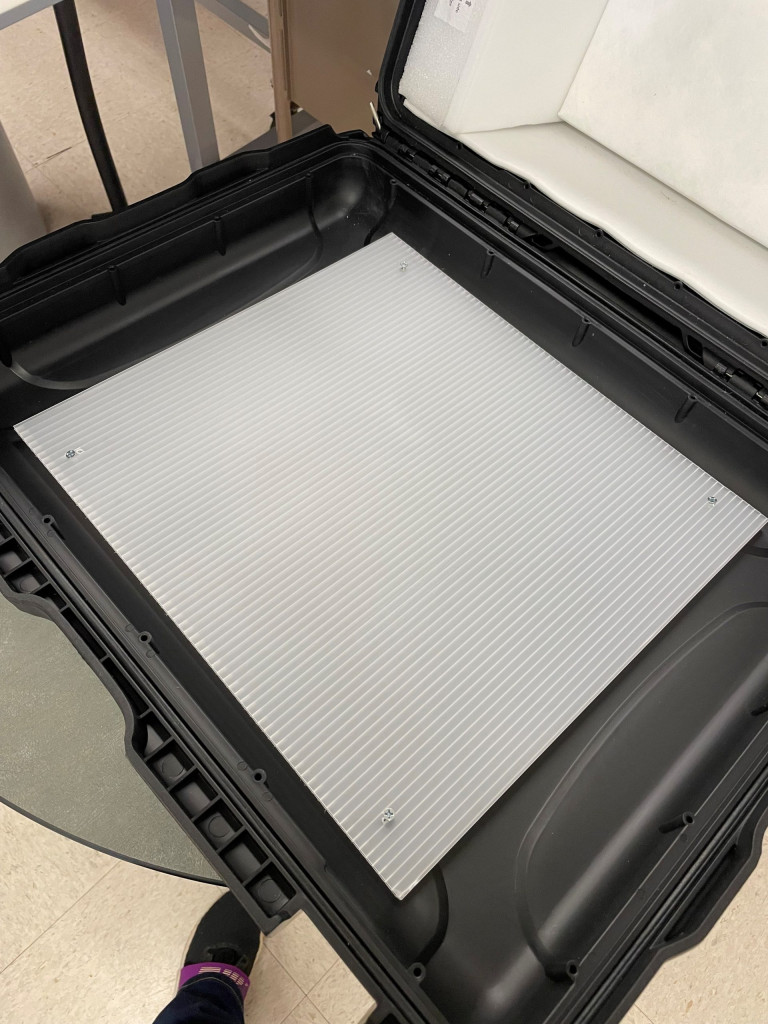

1. A waterproof, shock-proof rolling Nanuk 950 case (similar to a Pelican case) was purchased.

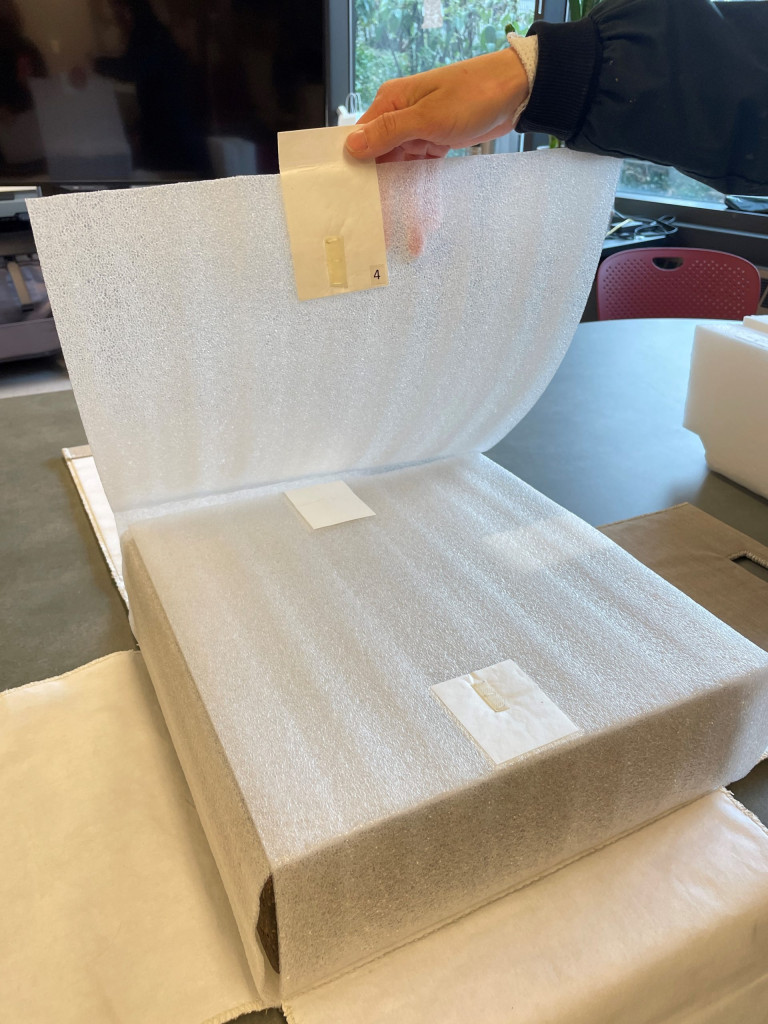

2. The interior was customized with foam and supports.

3. The lid was fashioned with a Tyvek pillow screwed to the top with an interior Coroplast sheet.

4. The cornerstone was wrapped around all sides in a foam sheet with four flaps.

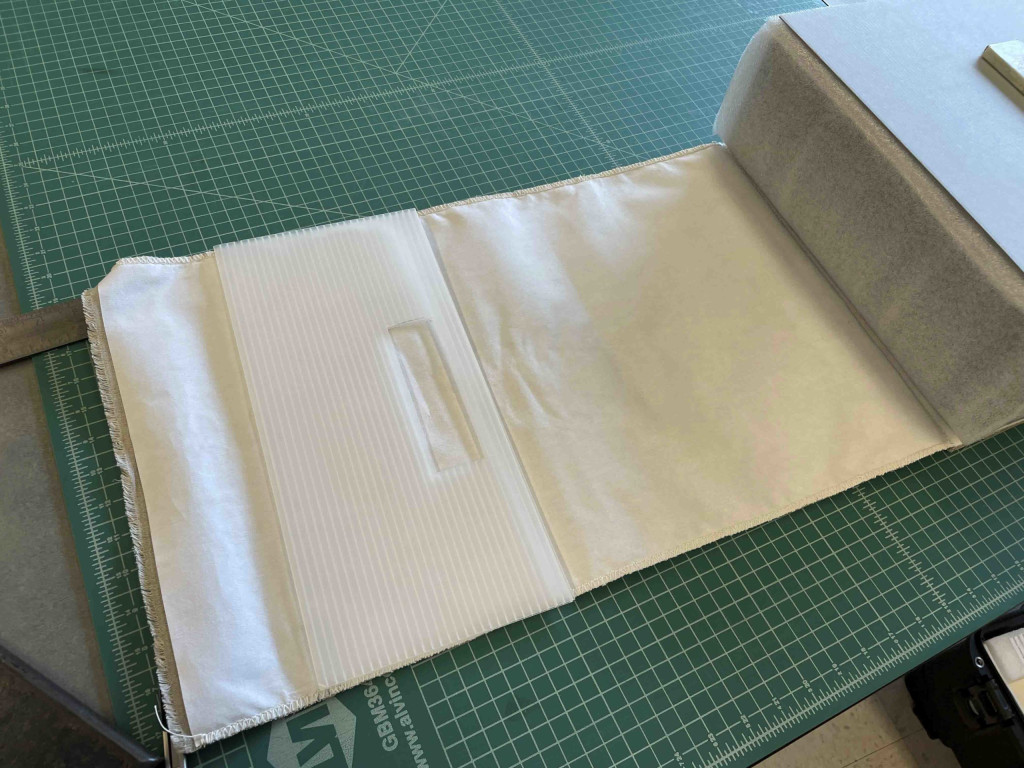

5. A cloth wrapper with custom handles was sewn to support the tablet during insertion into and retrieval from the case.

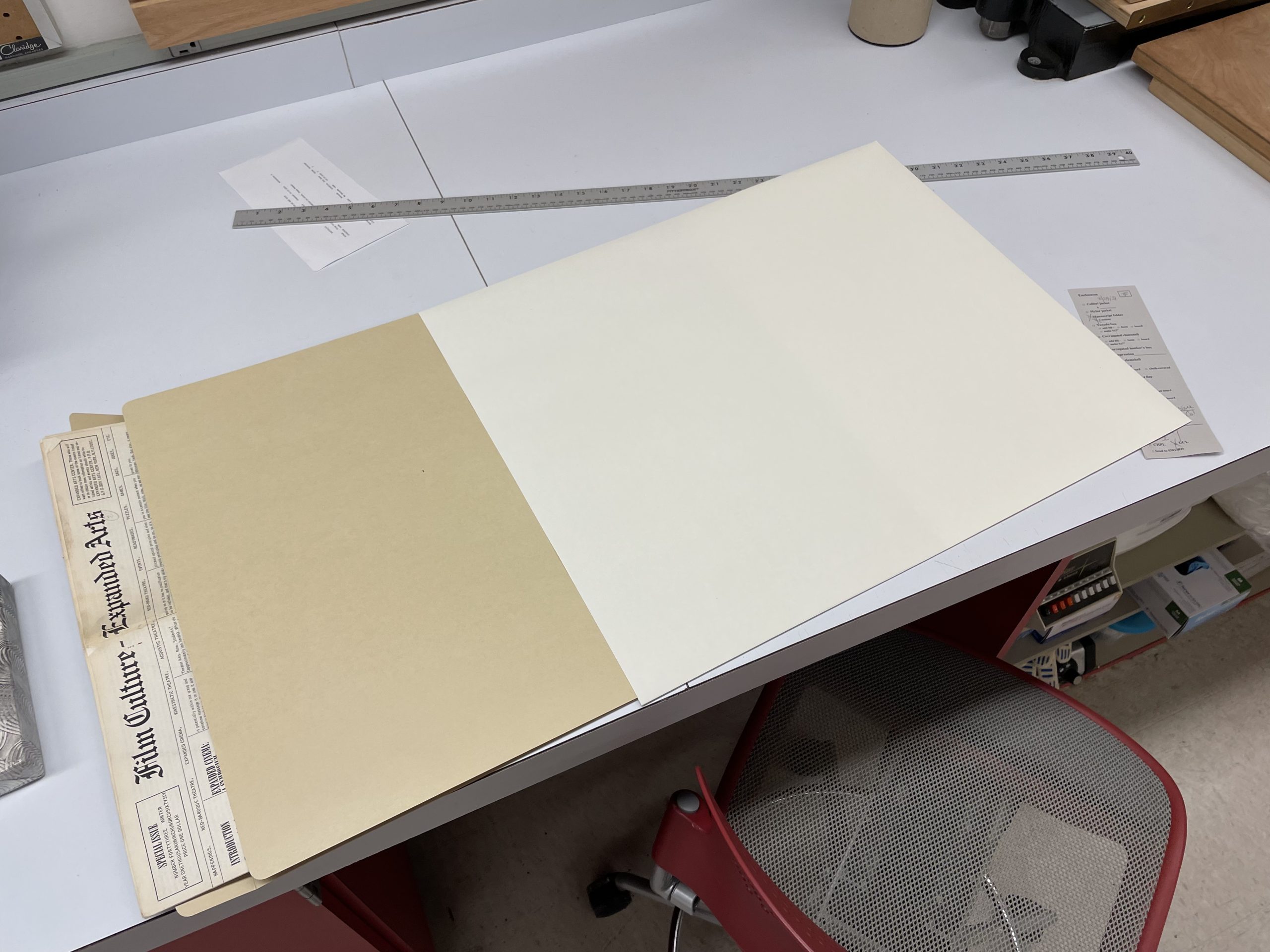

In addition, life-size surrogate photographs were printed by Jessica Ebert and stored in a polyester sleeve within the case. These images may prove even more useful during exhibition or teaching than seeing the actual tablet as they were captured with raking light that beautifully highlights the cuneiform writing. They could even be used as an alternative to handling the heavy tablet.

To help guide future librarians on how to handle the cuneiform tablet in the future, handling instructions were provided, a handling video was created, and a QR code of the video was pasted onto the case. Check out the video below.

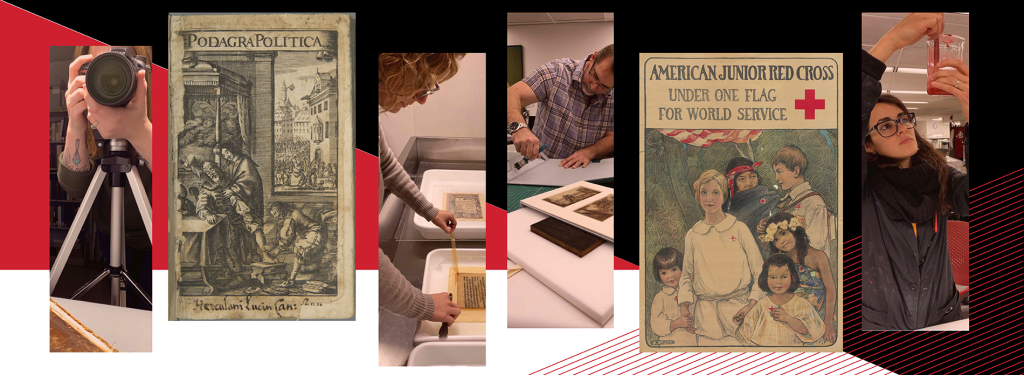

I was appreciative to have been able to hearken back to my object’s conservation experience working at the Musical Instrument Museum. My prior experience helped guide me to dust the tablet and store surface cleaning samples, however, this was a project that took me out of my library conservation comfort zone. The knowledge required to house such an object (and the amount of textile sewing used to create the cloth wrapper!) gave me even more appreciation for the work objects and textile conservators do to preserve our oversized and heavy materials – especially when transporting and taking them on and off display!

Ashleigh Ferguson Schieszer [CHPL] – Rare book and paper conservator

Video by Jessica Ebert