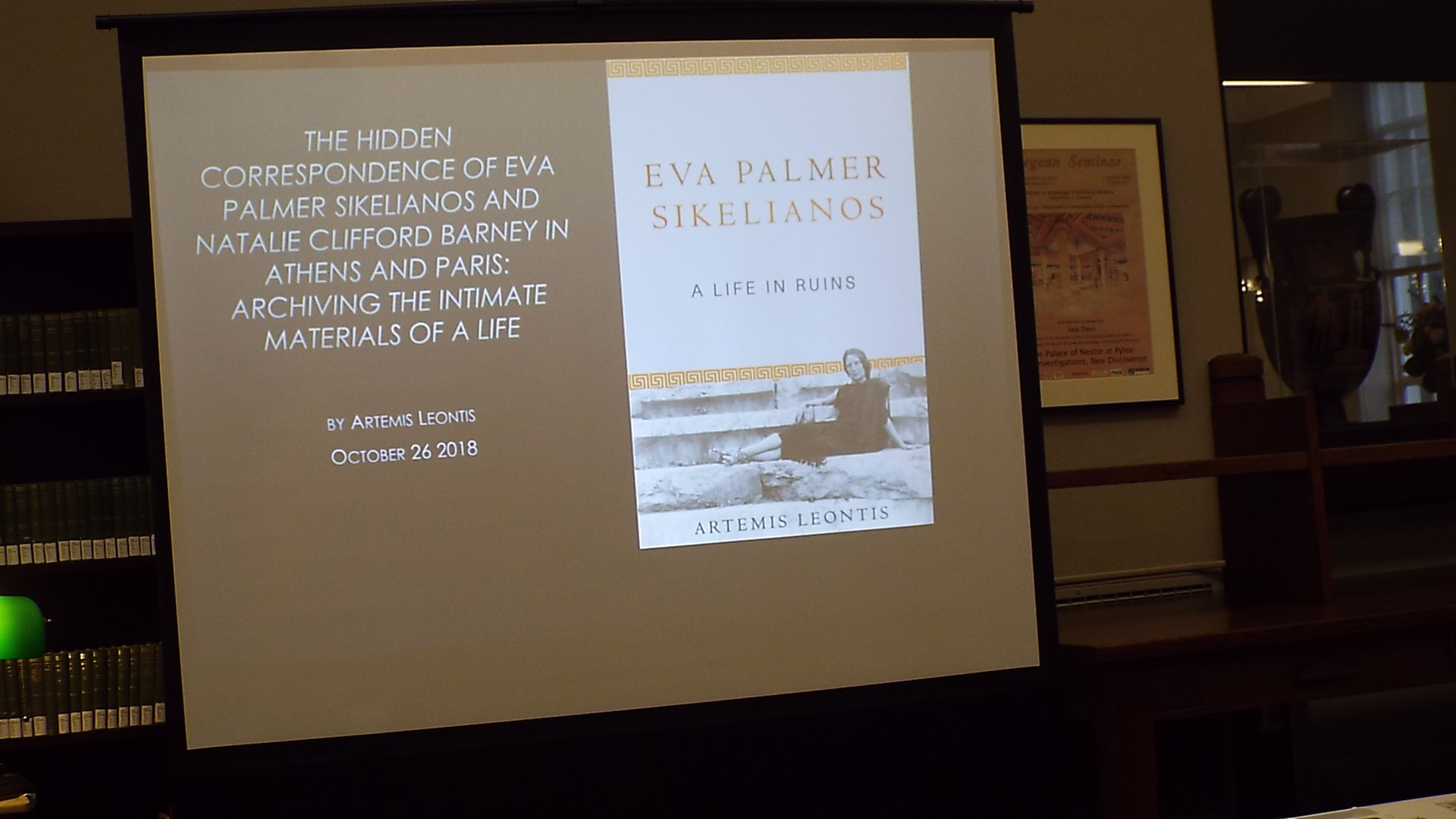

Introduction

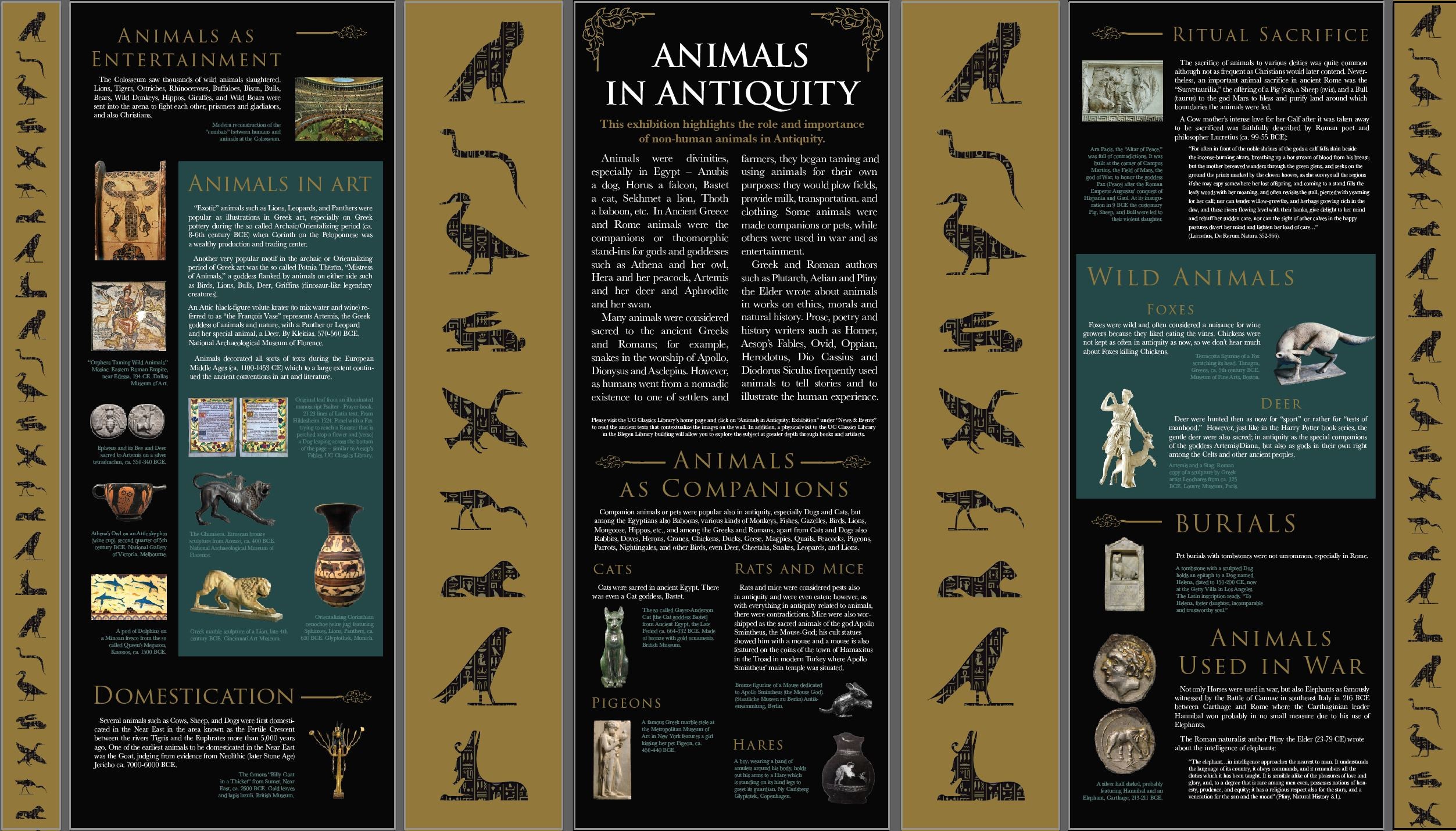

Considering the omnipresence of artistic and literary representations of animals in antiquity and the vital importance of their domestication for the rise and evolution of Western civilization, it is remarkable how little attention modern scholars have given this subject until the past 10 years or so. Of course, in that it correlates with a focus on freeborn Athenian and Roman men at the expense of all others. However, in recent years, classicists have extended their interests to include also women, children, slaves, “barbarians” and now, most recently, the vast topic of animals. The studies published so far, though, have only begun to scratch the surface.

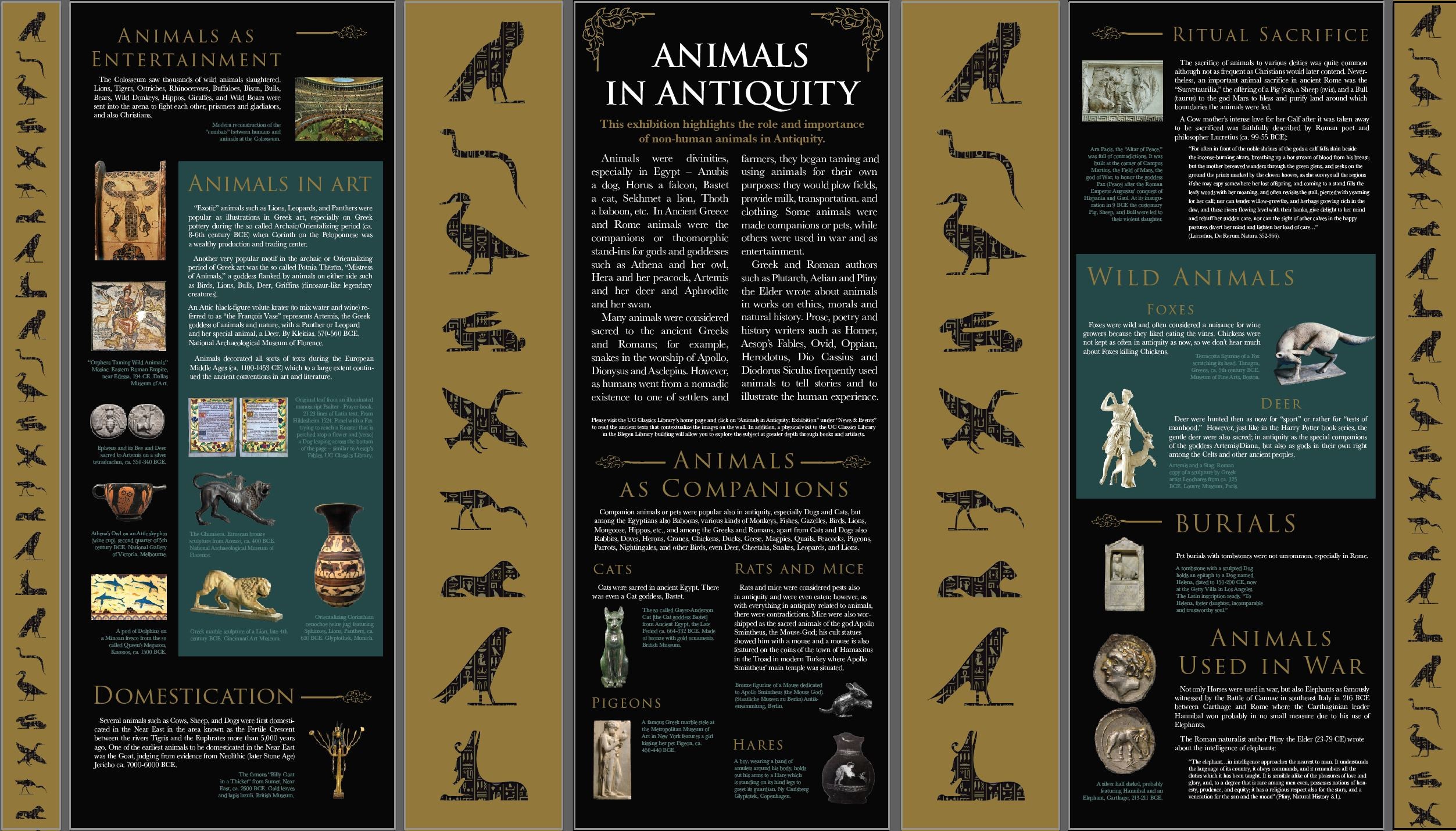

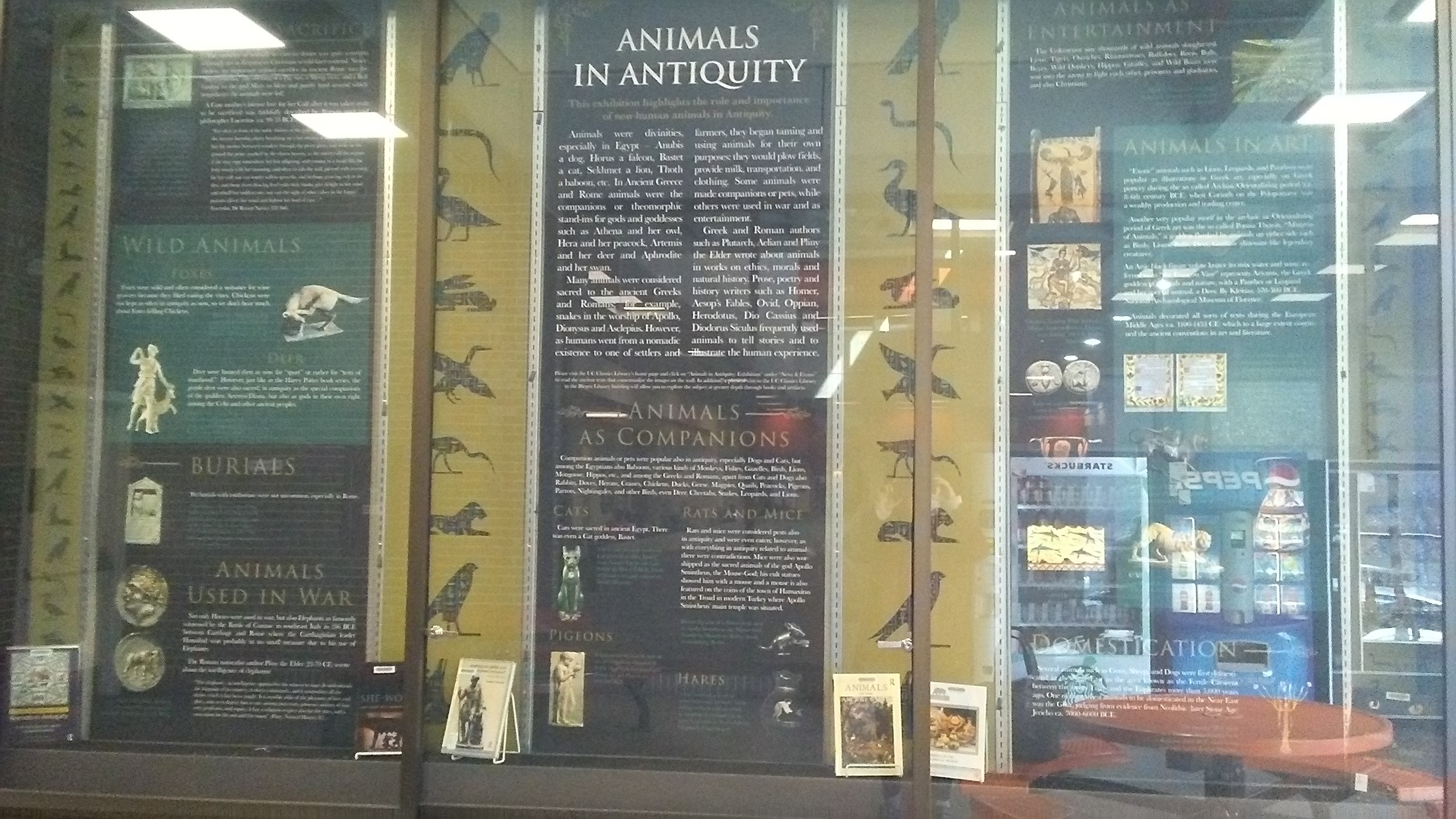

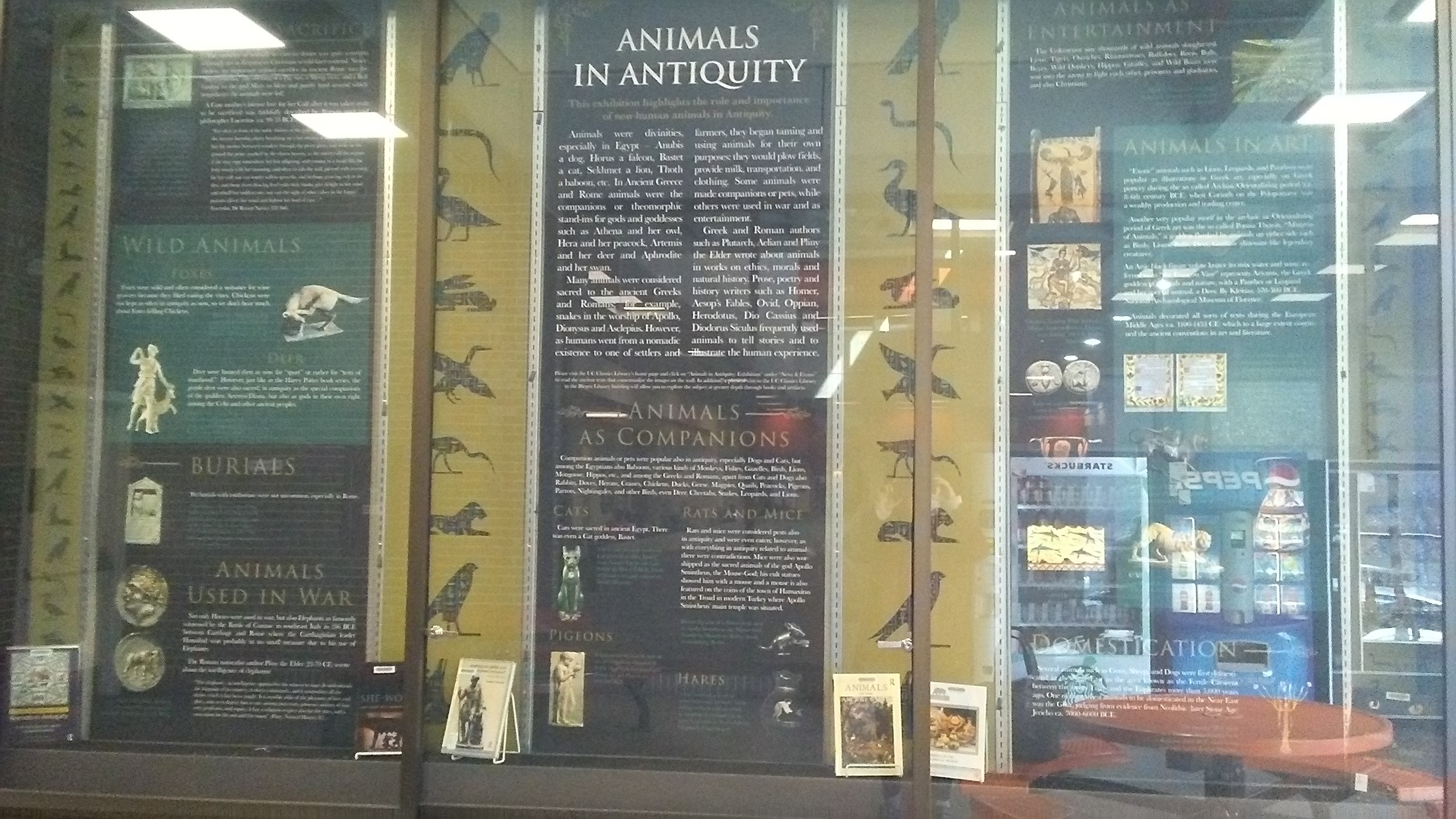

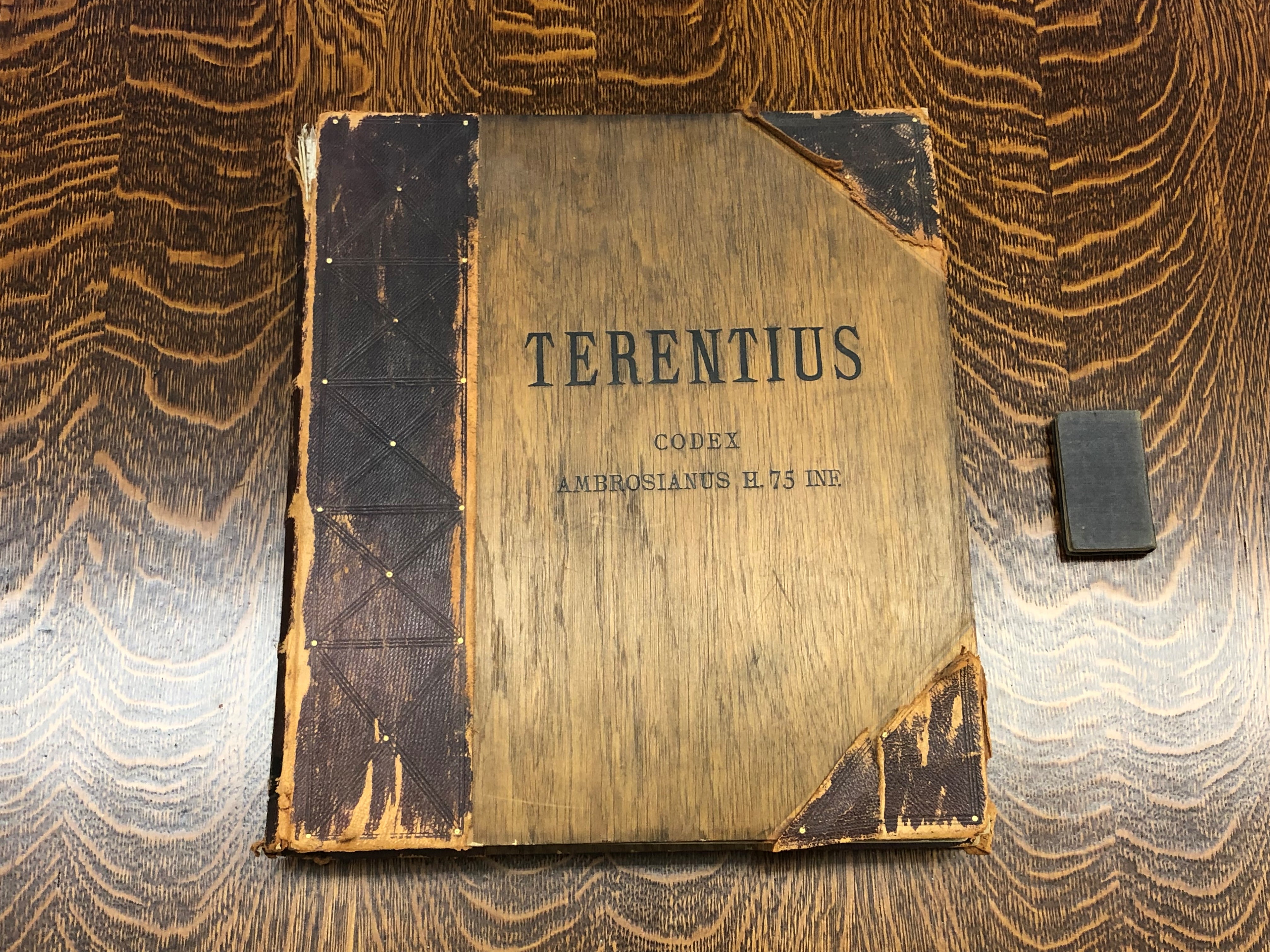

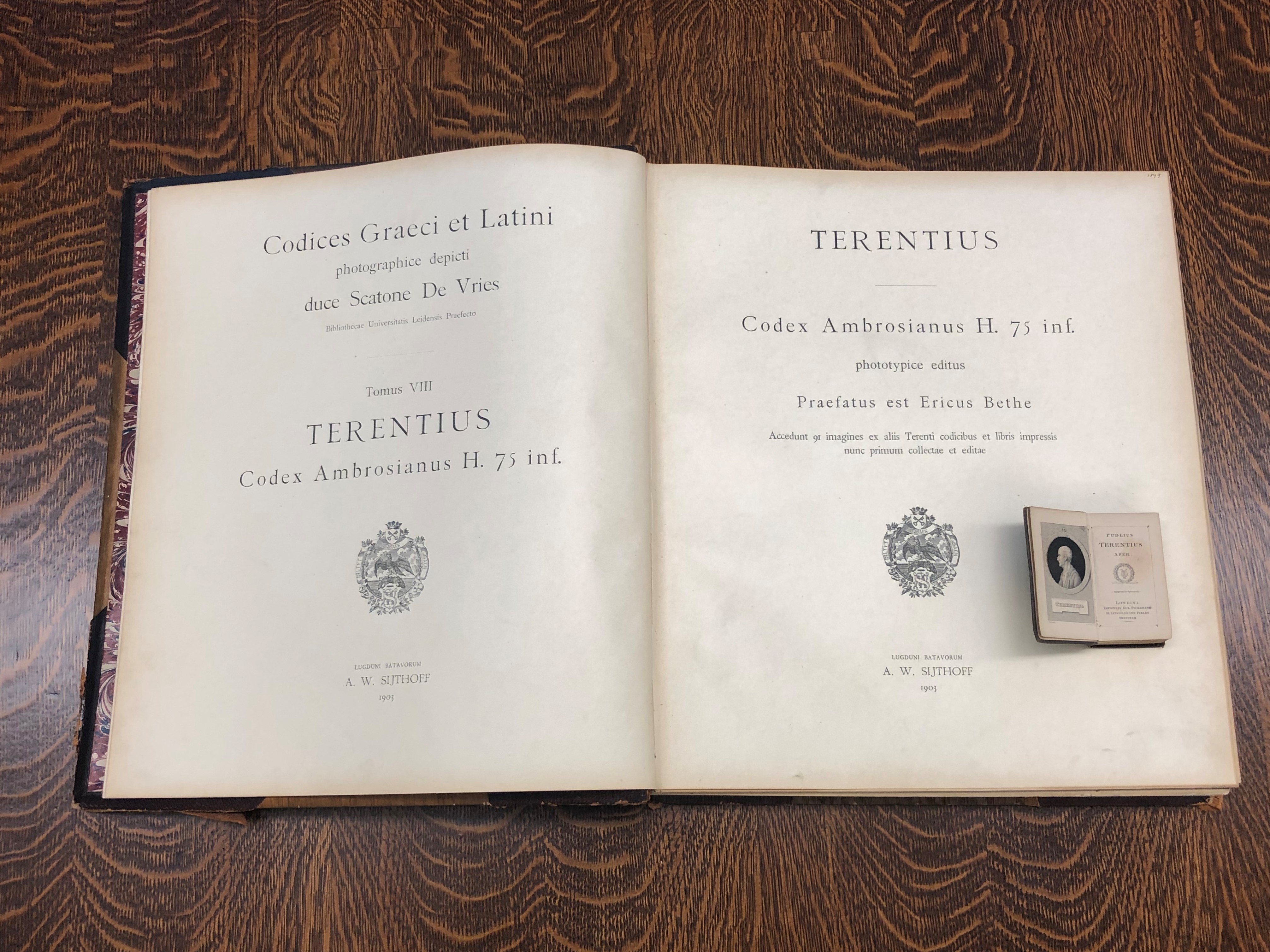

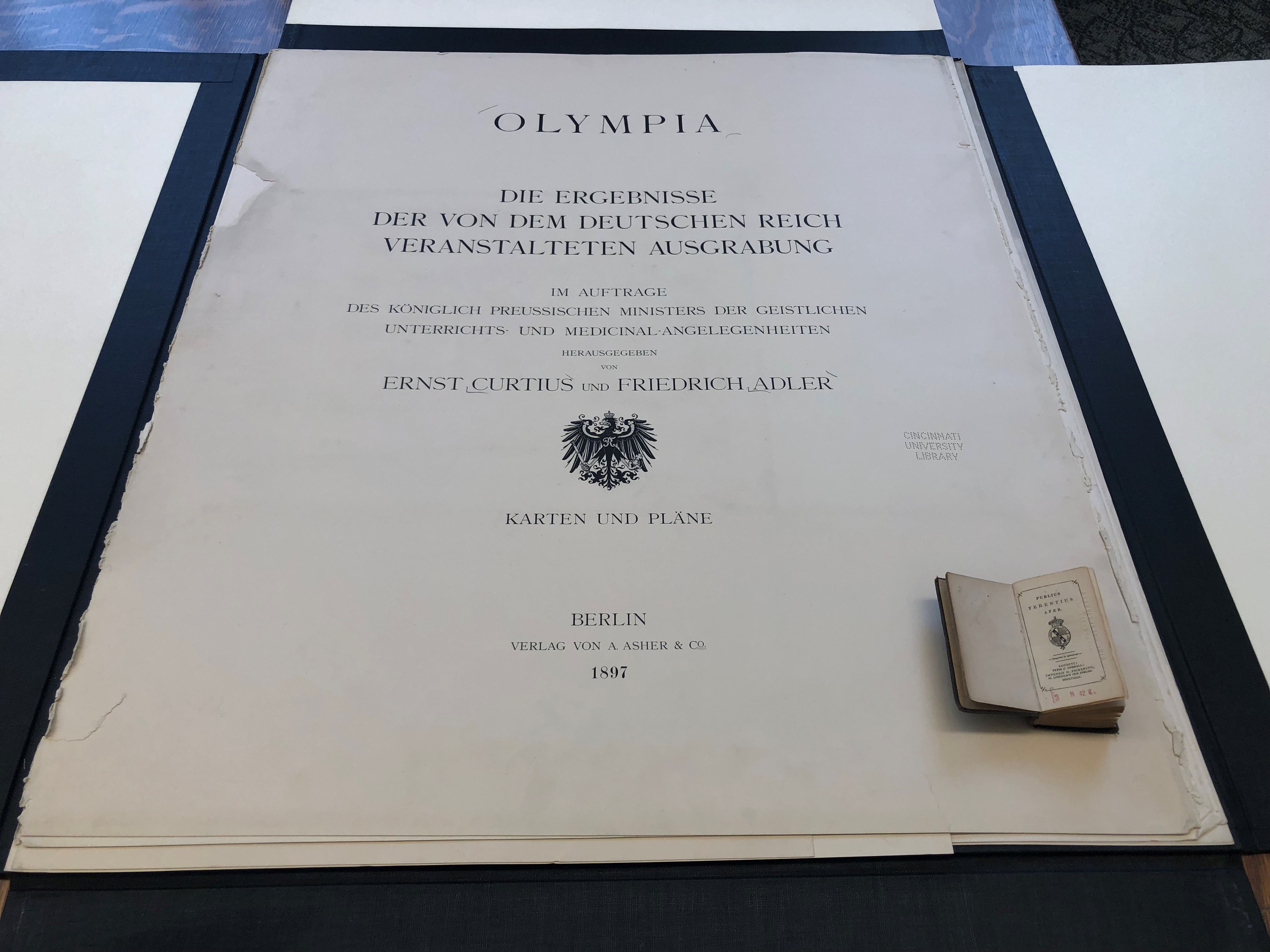

To represent more than 5,000 years of history and every kind of artistic and literary representation of and scientific theory about various animal species (with the Human animal species “exempted”) from a geographic area comprising much of Asia, Africa, and virtually all of Europe is, needless to say, an impossible task. This exhibition instead highlights a few notable depictions and narratives in art and literature from books and artifacts in the UC Classics Library relating to animals, i.e., how Humans in antiquity viewed other animal species.

Animals in antiquity were divinities, especially in Egypt – Anubis a Dog, Horus a Falcon, Bastet a Cat, Sekhmet a Lion, Thoth a Baboon and Ibis. In Ancient Greece and Rome they were the companions or theomorphic stand-ins for gods and goddesses such as Athena and her Owl, Hera and her Peacock, Artemis and her Deer, and Aphrodite and her Swan. Many animals were considered sacred to the ancient Greeks and Romans; for example, Snakes in the worship of Apollo, Dionysus, and Asclepius, Pigs in the cult of Demeter, Bees and Bears in the cult of Artemis.

As Humans went from a nomadic existence to one of settlers and farmers, they began taming and using animals for their own purposes. After their domestication, Bulls, Cows, Horses, Donkeys, Pigs, Sheep, Goats were used to plow fields, to provide milk, transportation, and clothing. Wild Boars were hunted for “displays of manhood” by well-to-do young men as were various Birds, Deer, Hare, and even Lizards. Some animals were made companions or pets such as Sparrows, Pigeons, Doves, Dogs, Cats, Monkeys and even such wild animals as Gazelles and Cheetahs. Animals in Greece, Rabbits, Dogs, Roosters, and Doves, were given as presents, also in courtship as “love gifts.” Mice and various kinds of Fish were eaten in antiquity, but they, too, could be pets and sacred to the gods. Animals such as Horses and Elephants were used in war; for example, in the second Punic War at the Battle of Cannae in 216 BCE, and as entertainment, for example, among the Romans at the Colosseum where Lions, Tigers, Elephants, Giraffes, Bears, Rhinoceroses, Hippopotamuses, Wild Donkeys, Hyenas, and Ostriches were forced to fight to their deaths. Greek and Roman authors such as Plutarch, Aelian, and Pliny the Elder wrote about animals in works on ethics, morals, and natural history and prose, poetry, and history writers such as Homer, Aesop’s Fables, Herodotus, Lucretius, Oppian, Ovid, Diodorus Siculus, and Dio Cassius frequently used animals to tell stories and to illustrate the Human experience.

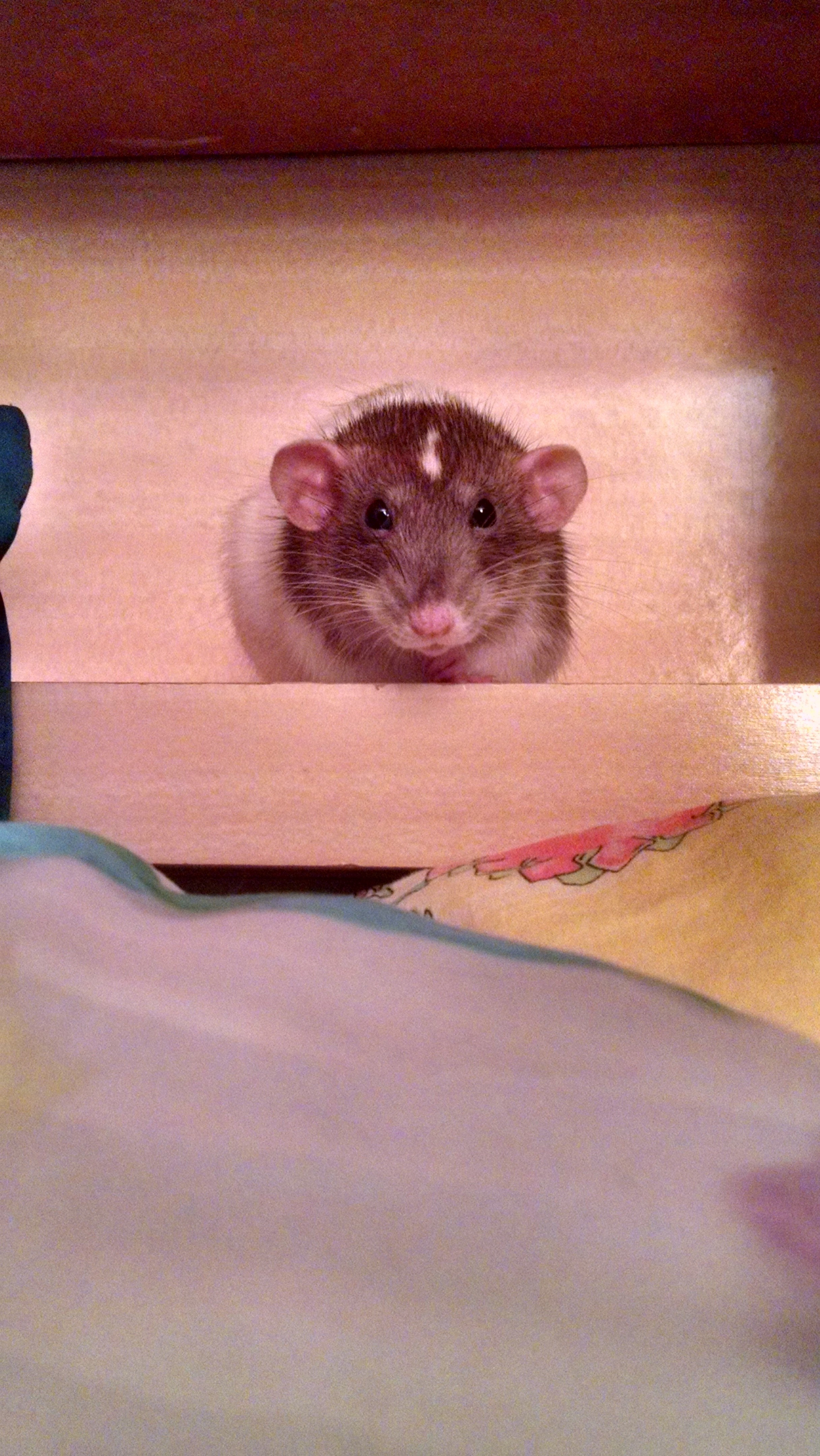

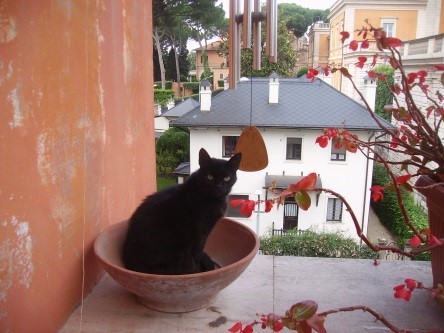

The exhibition (text written and images and ancient text passages selected by Rebecka Lindau) is dedicated to the memory of Cincinnatian Dog Tetris, Pig Georgi, and Rat Nug, Roman Cats Cleopatra and Francesca, Florentine Cats BJ and Ban Ki-Moon, and Roman Pigeon Cristoforo Colomba.

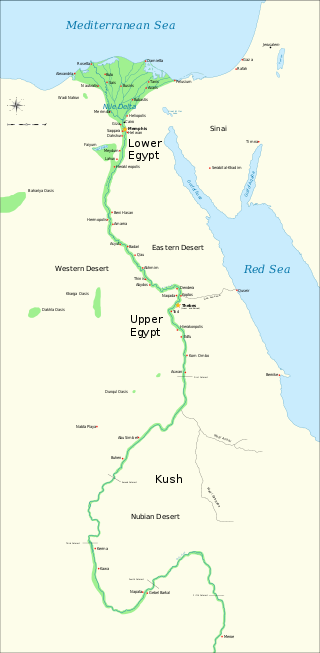

The term antiquity can be applied to different parts of the world. “Antiquity” in this context refers to western classical antiquity, especially ancient Greece and Rome, but also to areas which influenced and preceded them, the ancient Near East and Egypt, and the Minoan and Etruscan civilizations.

Ancient Near East (c. 3200-6th century BCE)

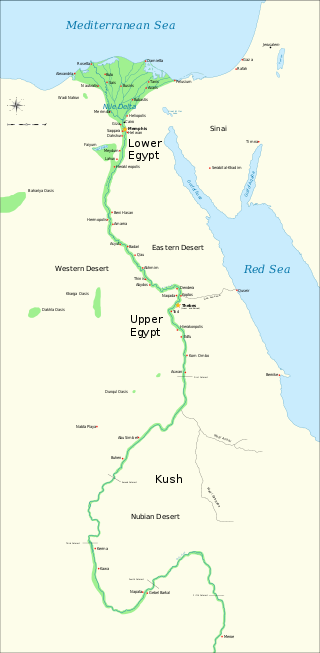

Ancient Egypt (c. 3100-30 BCE)

Minoan Crete (c. 2700-1400 BCE)

Mycenaean Greece (c. 1400-100 BCE)

Ancient Greece, Archaic period (c. 750-490 BCE)

Etruscan Civilization (c. 900-3rd century BCE)

Roman Empire (during the time of Emperor Augustus, b. 63 BCE-d. 14 CE)

Several animals such as Cows, Sheep, and Dogs were first domesticated in the Near East in the area known as the Fertile Crescent between the rivers Tigris and the Euphrates more than 5,000 years ago. Before the invention of weapons, our human ancestors were themselves hunted as easy prey animals without fangs and claws to defend themselves and with limited ability to run, jump, and climb.

Eventually, with the invention of spears and arrows the tables turned and Humans began to hunt other animal species; however, meat, contrary to the stereotypical image of the “cave man,” constituted a very small portion of the prehistoric diet. Most of the food was collected by so called gatherers, often women, who gathered roots, nuts, seeds, grains, wild mushrooms, wild olives, wild figs, and other wild seeds, fruits and berries. The killed animals, rather than being eaten, may originally have been offered to please or plead with the gods, a custom that continued in ancient Greece and Rome (ca. 1400 BCE-4th century CE). No animal in pagan antiquity was killed strictly for food. The meat was shared by humans and their gods to whom the animals had been sacrificed on special occasions such as religious festivals, which in ancient Greece often included theater/music and athletic competitions, such as at the City Dionysia and the Olympic Games, all to honor particular gods and goddesses.

Animals in Ancient History and Art

One of the earliest animals to be domesticated in the Near East was the Goat, judging from evidence from Neolithic (later Stone Age) Jericho ca. 7000-6000 BCE. Neolithic farmers began to herd Wild Goats for milk and wool. Their browsing was also useful to clear away brush for planting and to prevent fires. Their dung was used as fuel and building material.

The famous “Billy Goat in a Thicket” from Sumer, Near East, ca. 2600 BCE. Made of gold leaves and lapis lazuli. British Museum.

A furniture plaque made of Elephant tusks (ivory) in the form of a browsing Goat, Neo-Assyrian from Nimrud, Near East, ca. 8th century BCE. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

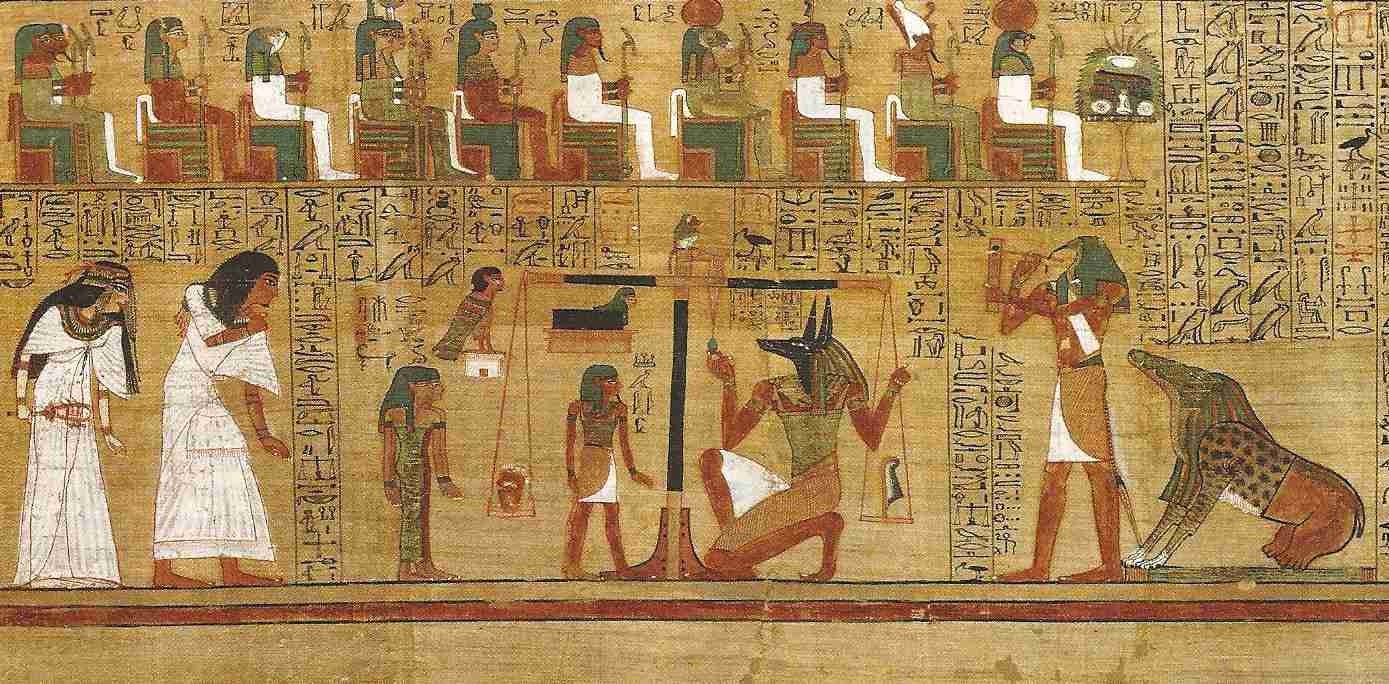

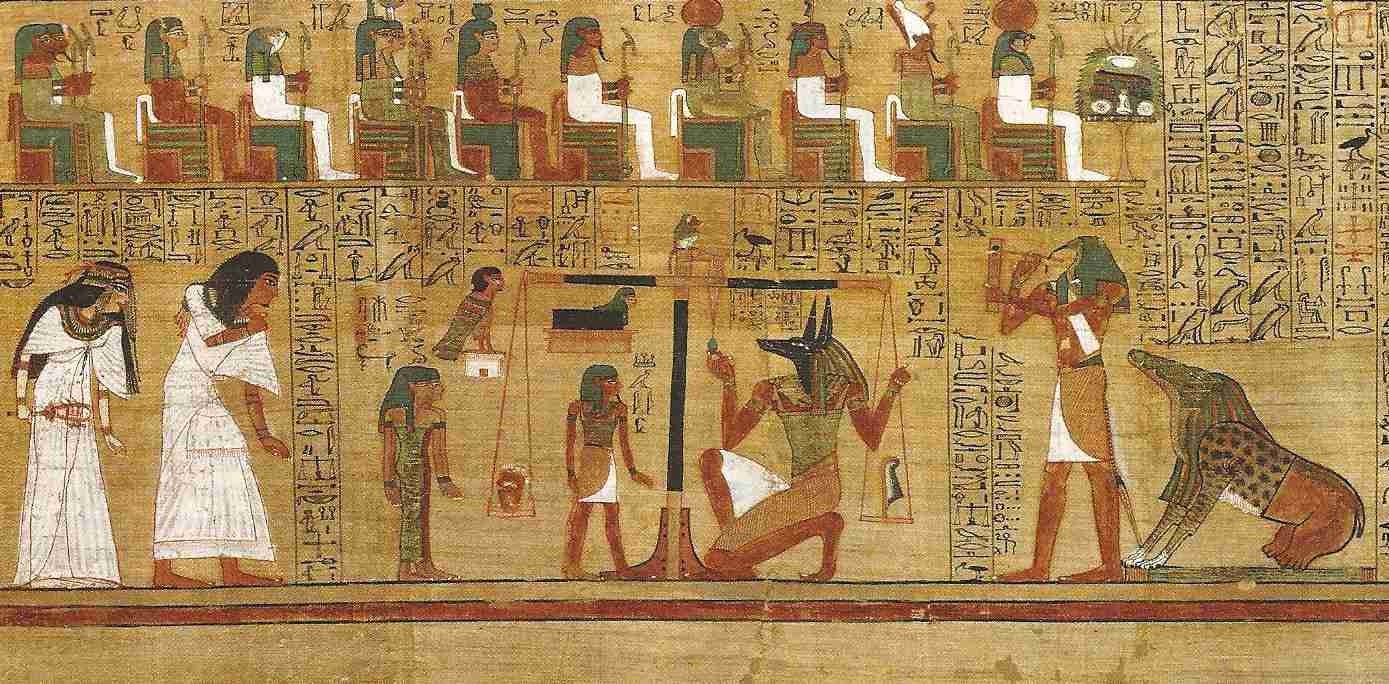

The pantheon of the ancient Egyptians was replete with animals.

A facsimile from 1898 of the “Papyrus of Ani,” in the Classics Library’s Reading Room features the Egyptian Book of the Dead. It depicts the royal scribe Ani and his wife Thuthu entering the Hall of Judgement, Ani’s soul, the Dog god Anubis testing the tongue of Balance, the Baboon god Thoth recording the result of the weighing with the Crocodile, Leopard, Hippo composite animal, Devourer of the Unjustified, standing by, the Falcon god Horus leading Ani to Osiris. During the 19th dynasty the dead were entombed with a copy of the Book of the Dead as a provision on their journey to Eternity. During the burial ceremony a priest would read from this book. The texts that it contained depicted in great detail the stages of rebirth, one of which was the weighing of the soul. The dead person’s heart was put in one pan of a scale, and in the other was placed the Feather of Ma’at (the Bird-like Goddess of Justice and Truth). The sacred writing (hieroglyphs) told the story along with colored vignettes on rolls from the papyrus plant.

There are numerous images of animals in antiquity on pottery, in frescoes, on coins, on temples, in figurines and sculptures. This is one of the most famous and beautiful depictions of Dolphins in antiquity.

A pod of Dolphins on a Minoan fresco from the so called Queen’s Megaron, Knossos, ca. 1500 BCE.

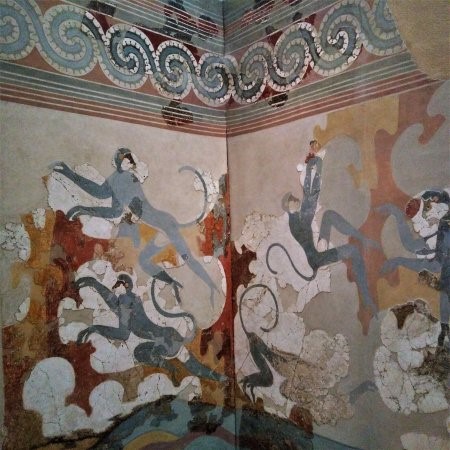

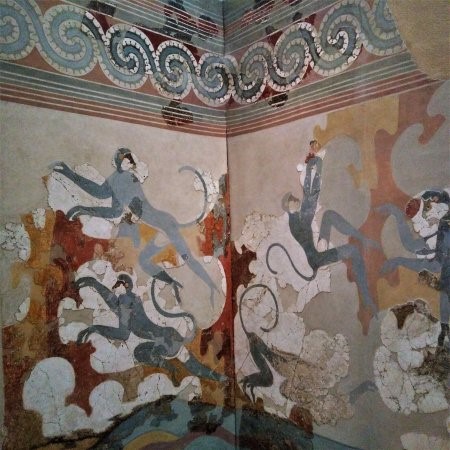

The Minoans (a Bronze Age civilization ca. 2700-1400 BCE on Crete and surrounding islands) displayed a remarkable sense of movement and delicate elegance in their art, especially when depicting nature scenes as in the so called Blue Monkey fresco from Thera (Santorini). Colors seem to have had special meaning to the Minoans, including the color blue.

Blue Monkey fresco. Thera (Santorini). Room Beta 6. West Wall, ca. 1500 BCE.

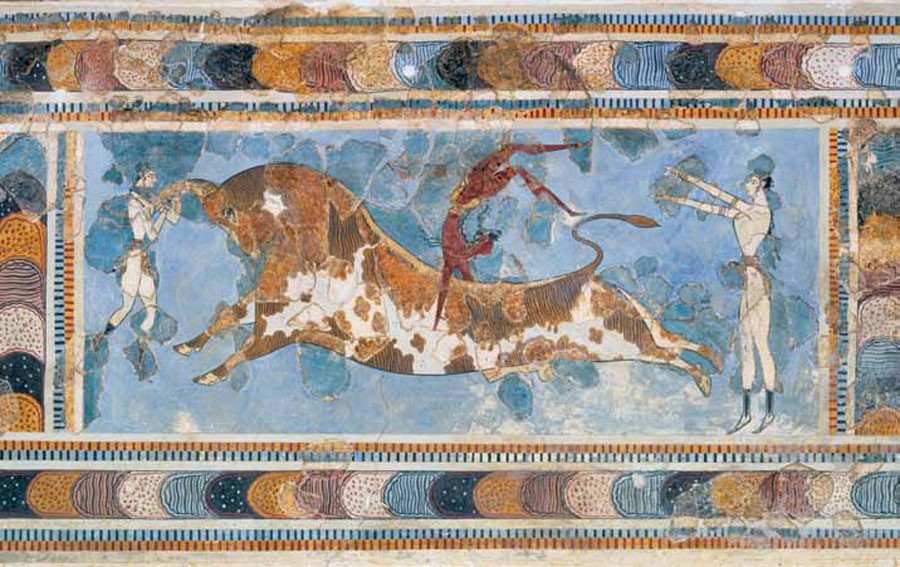

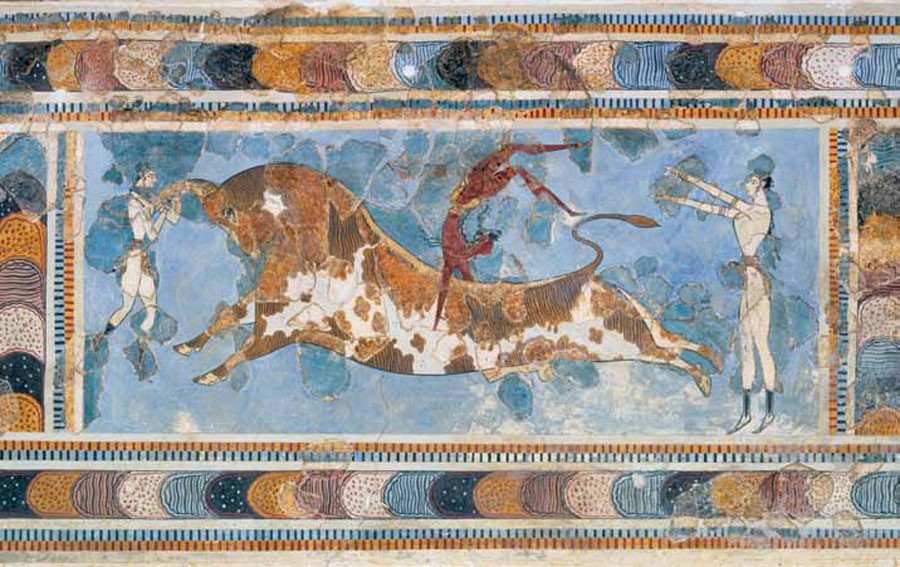

Both Minoan women (painted white) and men (painted red-brown) participated in acrobatic “performances,” which involved jumping over Bulls. The Bulls, however, were not killed as in contemporary Spanish bullfights, but were sacred to the Minoans.

The so called Bull-leaping fresco from the East Wing of the “Palace” of Knossos, ca. 1600-1400 BCE.

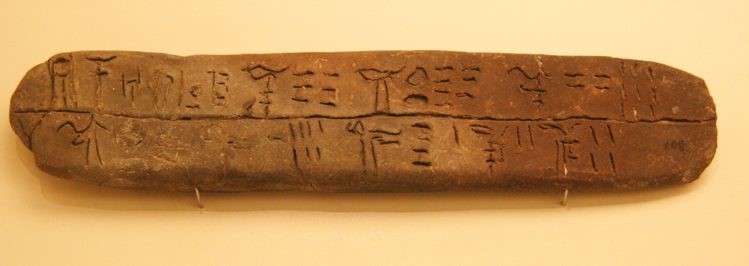

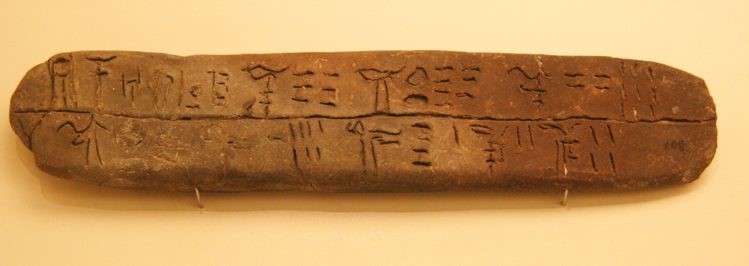

That animals were used in farming by the early Greeks is witnessed by texts on clay tablets from the Mycenaean civilization (ca. 1400-1100 BCE), written in the earliest form of Greek, the so called Linear B script. This tablet was discovered at Knossos on Crete and mentions Goats, Boars, Cows, and Bulls. Dated to ca. 1400 BCE.

The so called Lion Gate leading to the citadel of Mycenae on the Peloponnese is the most recognizable monumental art work of the early Greek Mycenaean civilization, ca. 1250 BCE.

Greek marble sculpture of a Lion, late-4th century BCE. Cincinnati Art Museum.

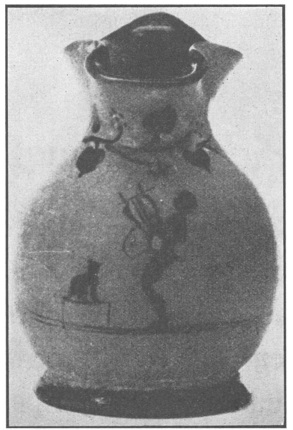

“Exotic” animals such as Lions, Leopards, and Panthers were popular as illustrations in Greek art, especially on Greek pottery during the so called Archaic/Orientalizing period (ca. 8-6th century BCE) when Corinth on the Peloponnese was a wealthy production and trading center.

Orientalizing Corinthian oinochoe (wine jug) featuring Sphinxes, Lions, Panthers, ca. 620 BCE. Glyptothek, Munich.

Panther or Leopard on a Corinthian alabastron (perfume bottle). Early 6th BCE. UC Classics Library. On loan from the UC Art Collection.

Panthers or Leopards on an Italo-Corinthian vase with handle, 6th century BCE. UC Classics Library. On loan from the UC Art Collection.

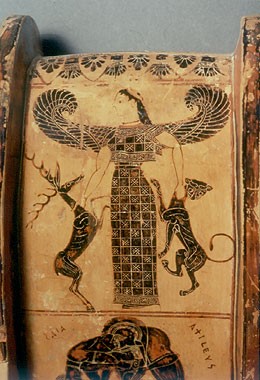

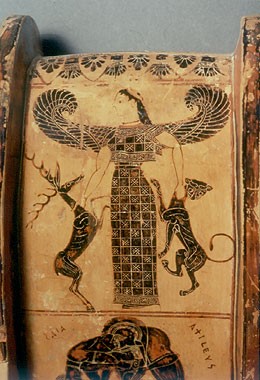

Another very popular motif in the archaic or Orientalizing period of Greek art was the so called Potnia Thērōn, “Mistress of Animals,” a goddess flanked by animals on either side such as Birds, Lions, Bulls, Deer, Griffins (dinosaur-like legendary creatures). There are also many “Master of Animals” depictions with male gods especially from the Near East, Mesopotamia, but also later from Assyria and Persia. It is not easy to interpret these images, but they could signal dominion over life or over the creation of life.

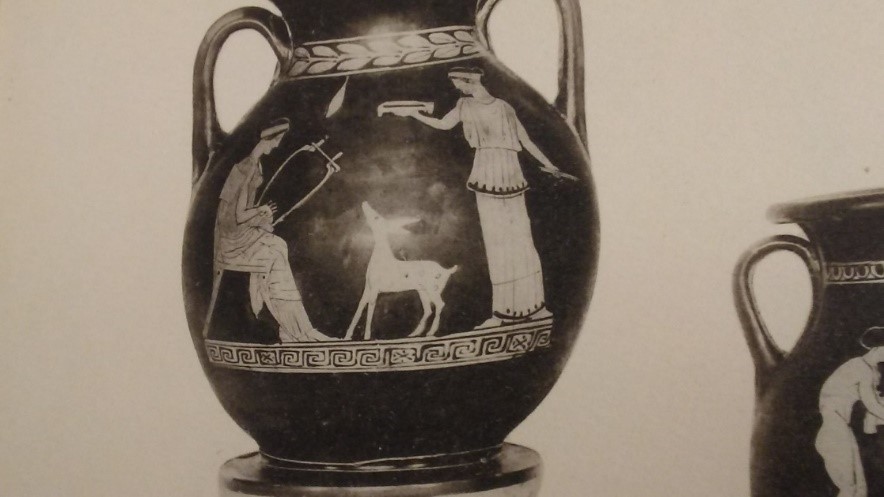

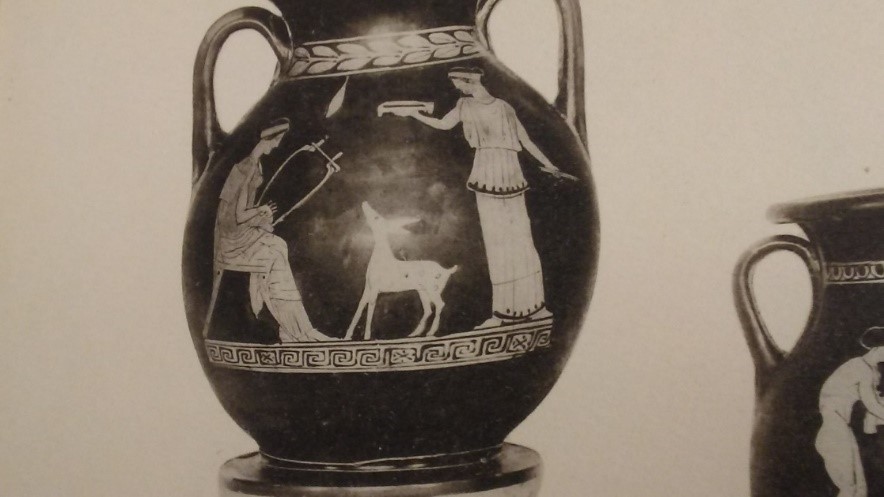

This handle of an Attic black-figure volute krater (to mix water and wine) referred to as “the François Vase” represents Artemis, the Greek goddess of animals and nature, with a Panther or Leopard and her special animal, a Deer. By Kleitias. 570-560 BCE. National Archaeological Museum of Florence.

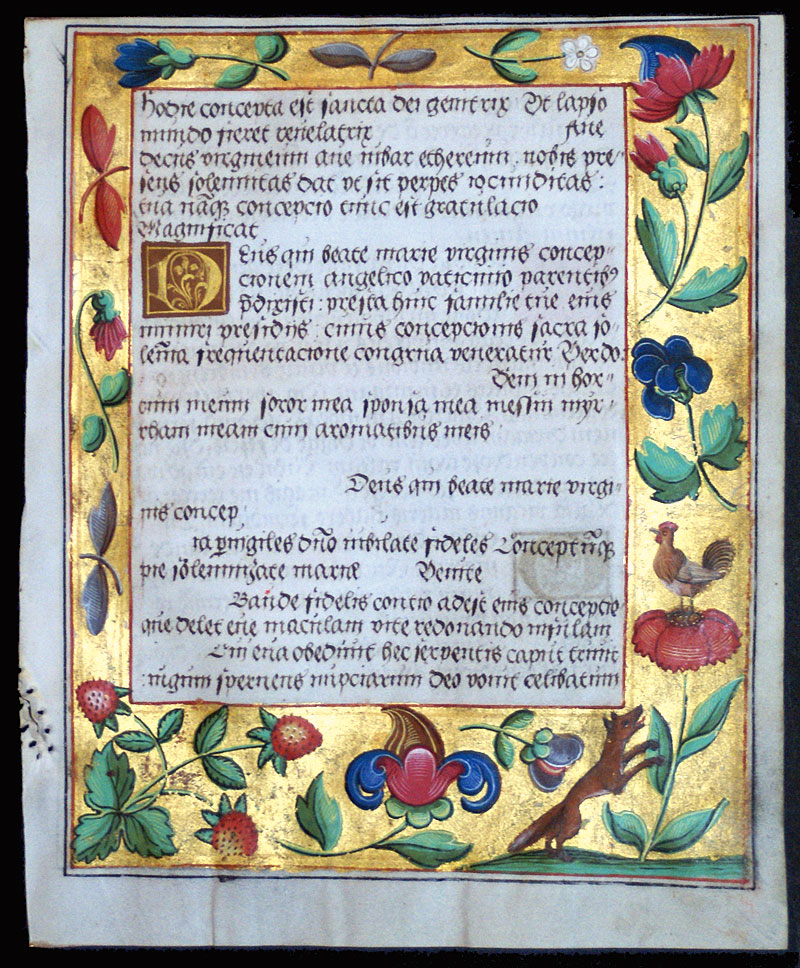

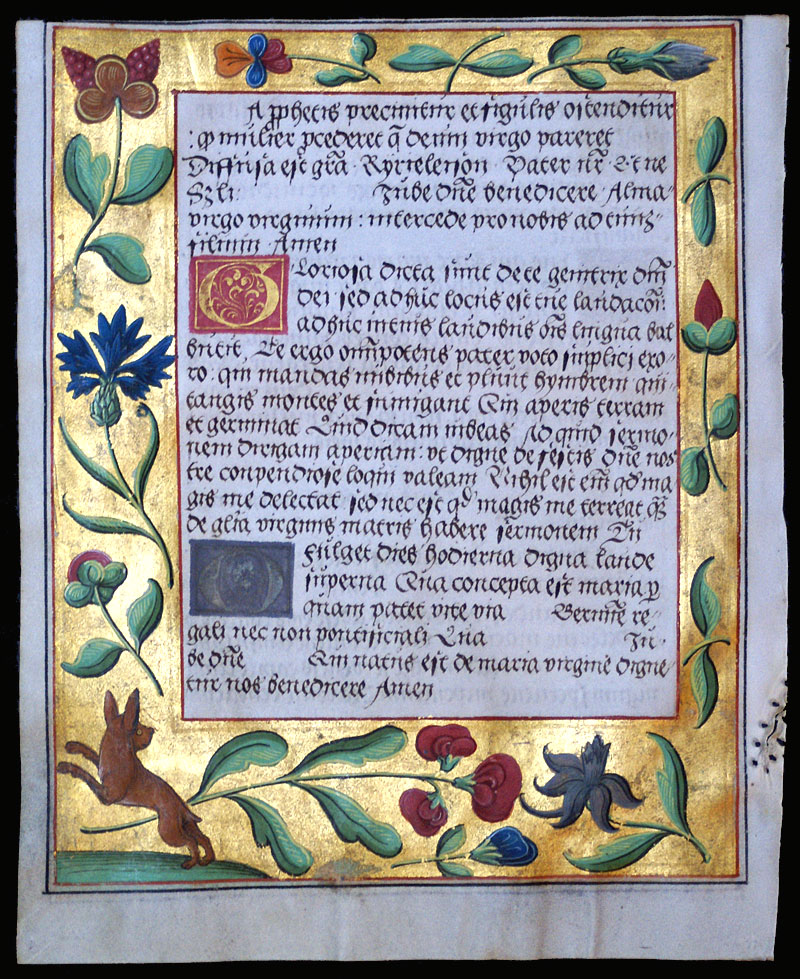

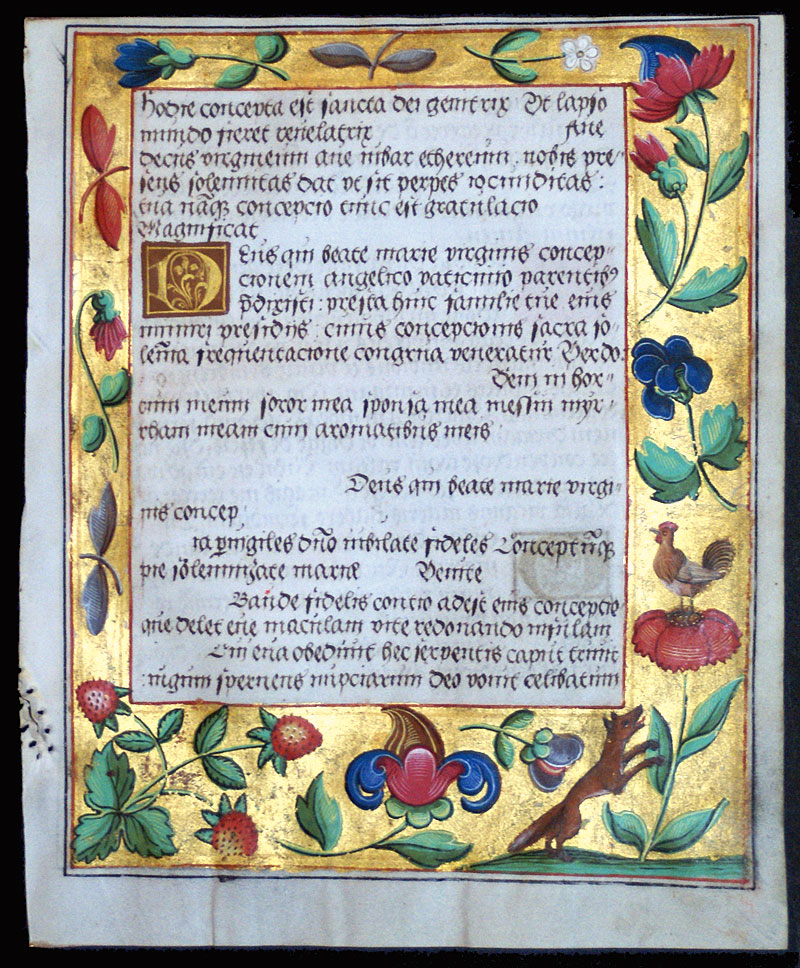

Animals decorated all sorts of texts during the European Middle Ages (ca. 1100-1453 CE) which to a large extent continued the ancient conventions in art and literature. Ancient literary texts were copied in so called scriptoria by Christian monks and nuns and ancient art and architecture could still be seen all over Europe.

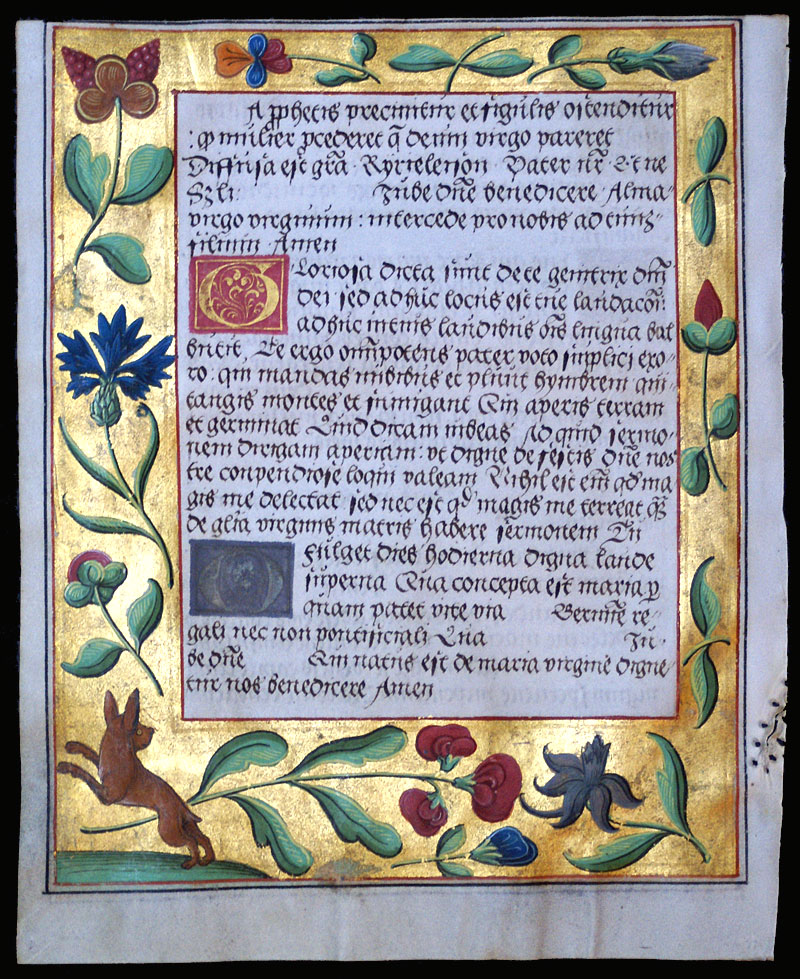

The margins of illuminated medieval manuscripts were frequently filled with every kind of animal, real and imagined. In fact, a technical term for marginal illuminations or “grotesques” is Baboon or Baboyne or Babewyne. Although most colors were plant based, the red pigment was usually made from the blood of various Insects. The pages of medieval manuscripts were made from the skin of animals, mostly from Calves, Sheep, and Goats.

Original leaf from an illuminated manuscript Psalter – Prayer-book. 21-23 lines of Latin text. From Hildesheim 1524. Panel with a Fox trying to reach a Rooster that is perched atop a flower and (verso) a Dog leaping across the bottom of the page – similar to Aesop’s Fables. UC Classics Library.

So called Bestiaries were one of the most popular medieval literary genres. A Bestiary was an illustrated codex describing various animals and plants usually accompanied by a moral lesson after the example of Aesop’s Fables from antiquity.

Lizard-Leopard and Horse-Ram-Boar composite animals. Liber Floridus (“Flower Book”) is a medieval encyclopedia about plants and animals, in part a “Bestiary,” compiled between 1090 and 1120 CE by Lambert, Canon of Saint-Omer. This copy in the Classics Library is a facsimile of the oldest of the known copies of the manuscript. The original is in the Library of the University of Ghent.

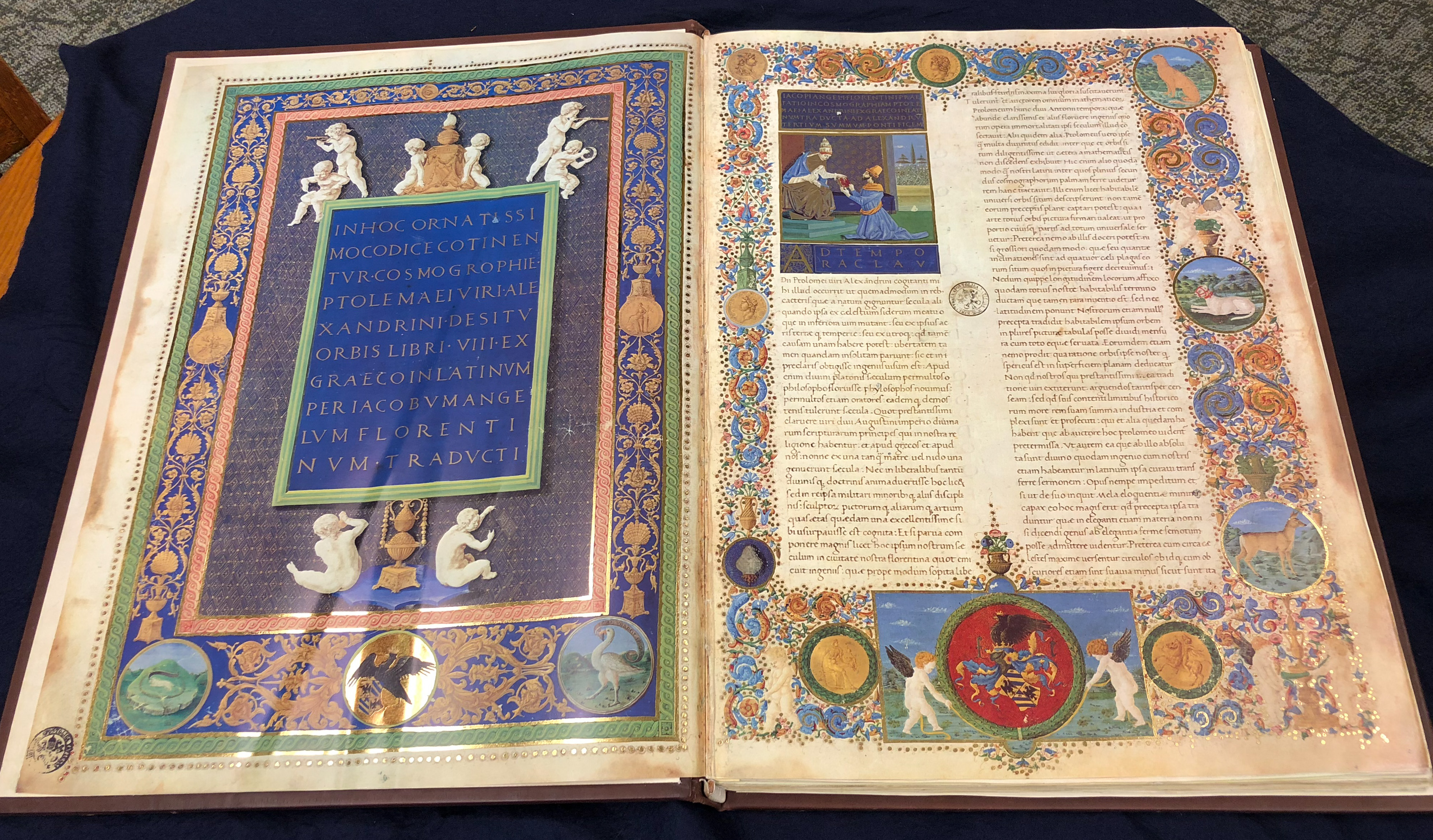

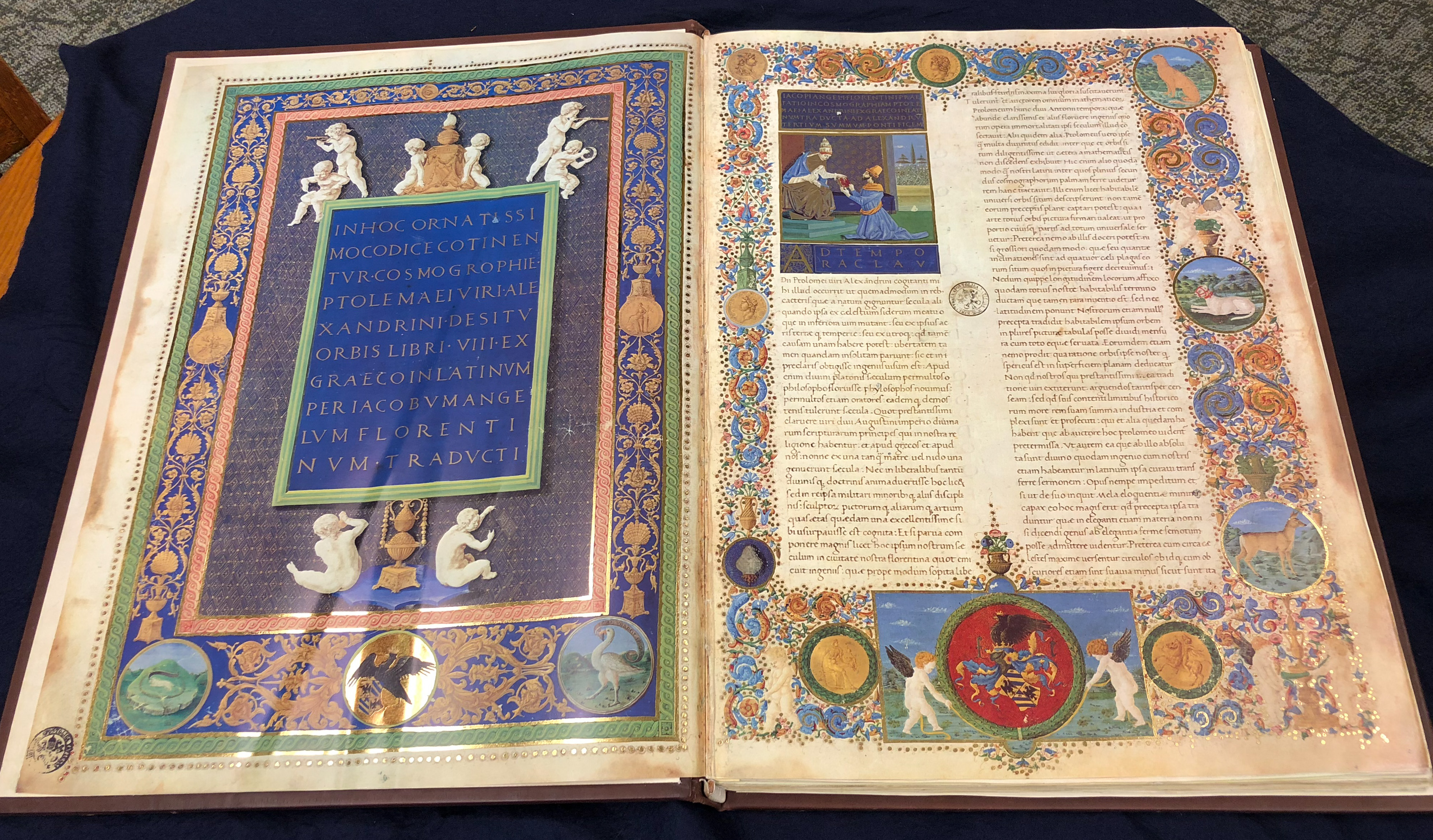

In this rare facsimile (Cod. Urb. lat. 277) of the Latin translation by Jacopo D’Angelo from 1406 of an atlas by Ptolemy from the 2nd century CE, animals — Leopard, Dog, Deer, Swan(?), Eagle, Ermine, etc. – in the marginal illustrations abound. UC Classics Library.

The animals featured could also be hybrid “fantasy” animals such as the Centaur (Horse-Man), Sphinx (Lion-Woman), Hippocamp (Fish-Horse), Minotaur (Bull-Man), Griffin (Eagle-Lion), Typhon (Snake-Man), Medusa (Snake-Woman), and Chimaera (Lion-Goat-Snake).

Possibly the most famous depiction of a fantasy animal in classical antiquity is an Etruscan sculpture of the Chimaera. The Etruscans (ca. 900-3rd century BCE), a civilization dominating central and northern Italy before the Romans, and who even served as early kings of Rome itself, were anthropocentric in their art but displayed a similar exuberance in colors and movement as the Minoans once had done. Whereas the Minoans had the Minotaur, at least according to later Greek art and literature, the Etruscans had the Winged Horse, Griffin, Typhon, Medusa, and the Chimaera although the Minotaur survived also among the Etruscans. Much of what we know about Etruscan art comes from tomb and vase paintings. In fact, many of the Greek vases admired in museums all over the world were discovered in Etruscan tombs. The fantasy animals are generally thought to be demons encountered upon death in the underworld. The famous She-Wolf in the Capitoline Museums in Rome probably also had Etruscan background although some scholars believe it to be medieval.

The Chimaera. Etruscan bronze sculpture from Arezzo, ca. 400 BCE. National Archaeological Museum of Florence.

Perhaps the most famous animal symbol from antiquity is the mother Wolf of Rome’s foundation myth. There are many versions of this myth as of the origin of the name of the city and its foundational year. The most popular story tells how the Wolf nursed and protected the twins Romulus and Remus after they had been abandoned on the order of the king of Alba Longa, an ancient city close to what was to become Rome. The Wolf cared for the twins in a cave known as the Lupercal, still shown to tourists at the southwestern foot of the Palatine Hill in Rome. Romulus later became the legendary founder and first king of Rome.

A bronze cast of the famous She-Wolf nursing Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome, in Cincinnati’s Eden Park was a gift to our city from the City of Rome under the Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini (1883-1945).

The She-Wolf with Romulus and Remus on a bronze sestertius from the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161 CE) to commemorate the 900th anniversary of the founding of Rome. Photo by Mike Braunlin.

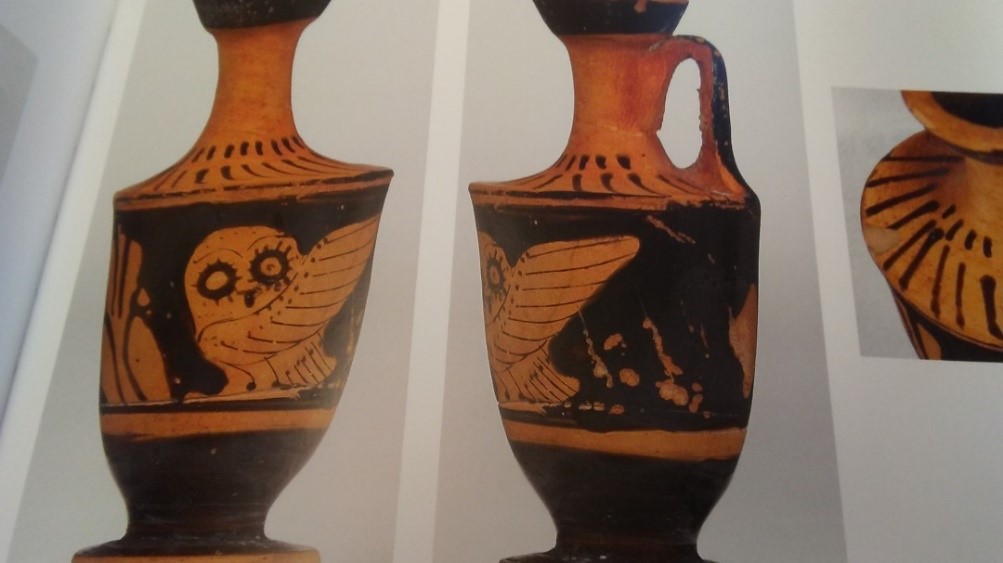

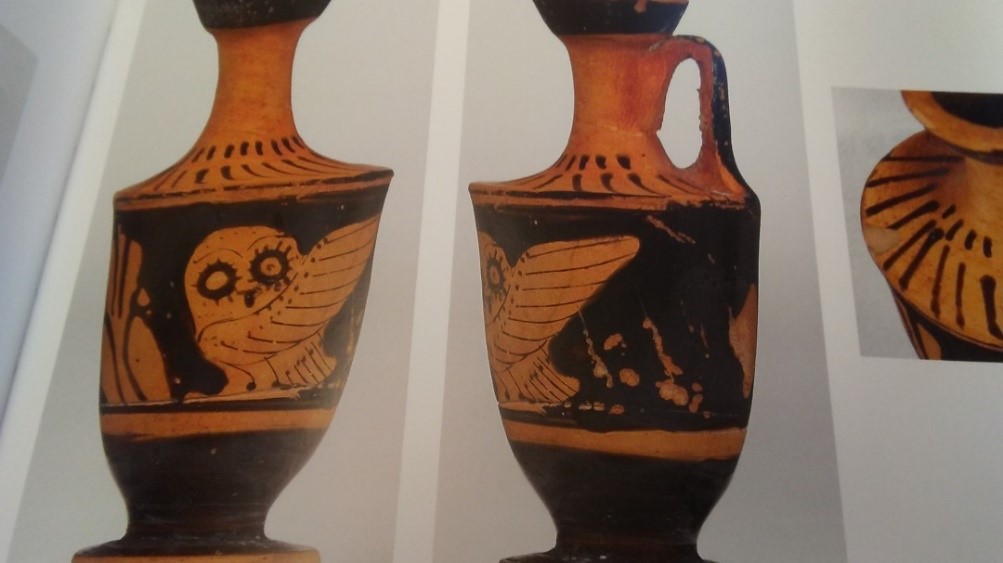

Almost as famous a symbol from classical antiquity as the Roman She-Wolf is the Goddess Athena’s Owl and by extension the symbol of Athens. Greek and Roman gods and goddesses were either featured with their animal companions/attributes or their animals were depicted alone as substitutes for the deity such as Athena and her Owl. The goddess was the patron deity of the city-state of Athens and its coins usually depicted the goddess on one side and her Owl on the other.

Owl on an Athenian silver tetradrachm, ca. 449-404 BCE.

Owl on an Attic skyphos (wine cup), second quarter of 5th century BCE. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

The Athenian Owl on a red-figure lekythos (oil container) from Nola, Southern Italy, ca. 4th century BCE. (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin) Antikensammlung, Berlin.

Many of the Greek city states, besides Athens, had animals (and deities) as symbols, for example.

Ephesus and its Bee sacred to Artemis on a silver tetradrachm, ca. 350-340 BCE.

Aegina and its Turtle. Silver stater, ca. 445-431 BCE.

Lycia (in modern-day Turkey) and its Tortoise and Boar. Silver stater, ca. 490-430 BCE.

Lycia could also be represented by a Panther or Leopard as on this silver hemiobol, ca. 400-390 BCE. Photo by Mike Braunlin.

This gives a sense of the tiny size of the hemiobol above as compared to that of an American penny. The artistic mastery of working in such a small space is quite astonishing. Photo by Mike Braunlin.

This coin featuring twin Panthers or Leopards along with a Lion on the reverse is also from Lycia. Silver stater, ca. 450-380 BCE. Most figures in ancient art were portrayed in profile, so when they appear with frontal faces as here and as the Panther/Leopard on the hemiobol, it is thought that they served an apotropaic function, i.e., to ward off evil spirits or bad luck. However, it could perhaps also be an artistic attempt at breaking with convention.

Syracuse, Sicily, and its nymph goddess Arethusa surrounded by Dolphins. Silver tetradrachm, ca. 310 BCE.

Syracuse could also be represented by an Octopus as on this Greek silver litra, ca. 466-405 BCE.

Carthage (present-day Tunisia, North Africa) by a Horse as on this electrum stater, ca. 310-290 BCE.

Akragas (modern Agrigento, Sicily) by a Crab as on this silver didrachm, ca. 495-478 BCE.

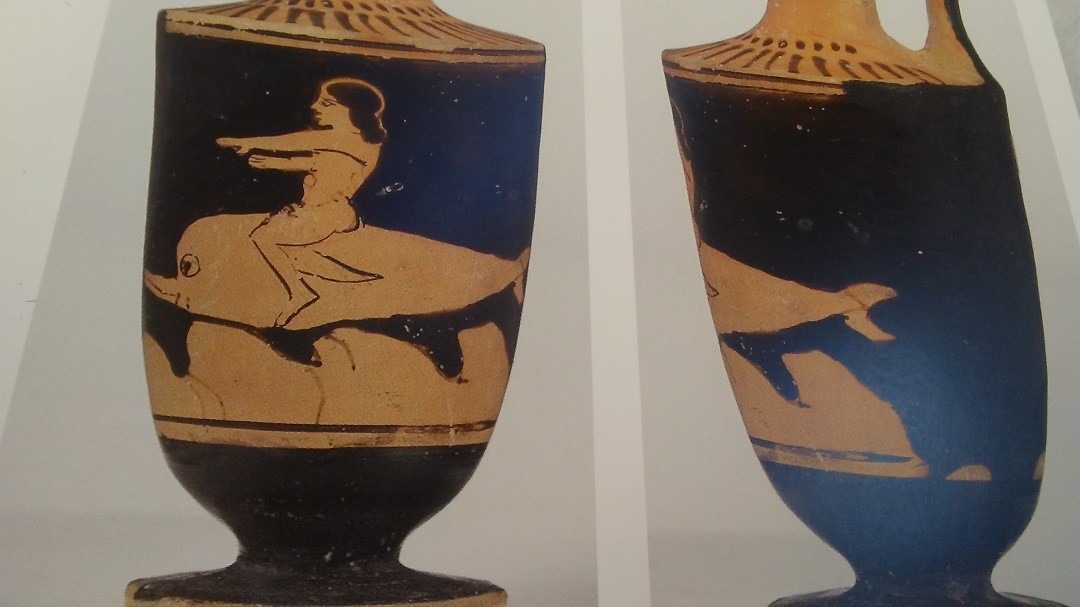

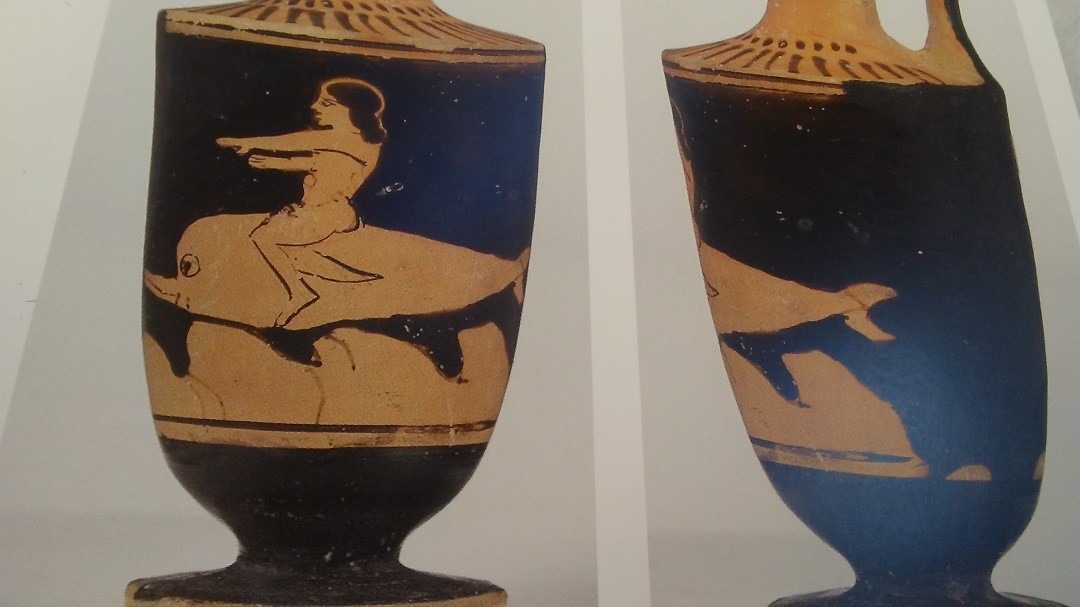

Tarentum (modern Taranto, Calabria) by its eponymous founder Taras riding a Dolphin. Silver didrachm, ca. 3rd century BCE.

There were many tales in antiquity of people being rescued by Dolphins such as Arion, the purported inventor of the dithyramb, which, according to Greek philosopher Aristotle, was the origin of Greek tragedy, who after being kidnapped by pirates escaped on the back of a Dolphin or so the story goes.

Attic red-figure lekythos with a young man riding on a Dolphin, ca. 500-450 BCE. (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin) Antikensammlung, Berlin.

The famous cult statue of Artemis and her temple at Ephesus, now in modern-day Turkey, were counted among the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. The statue is full of animals — on the goddess’ dress, headgear, and sandals. The identification of the bulbous protrusions in the front has been hotly debated. The most logical interpretation is of the Goddess of Nature nursing all her children – animals and plants alike — or possibly seeds to feed life. The temple’s beehive organization with priestesses called bees and priests drones may point to a representation of eggs. A wildly speculative and nonsensical theory is that they represent Bull scrota.

A replica of the cult statue of Ephesian Artemis in the Museum of Ephesus. The earliest temple and statue date back to the Bronze Age although this copy is dated much later. Christians eventually destroyed the temple and statue in the 5th century CE.

Artemis of Ephesus worshiped “in Asia and all the world.” A Roman copy of an original from the 2nd century BCE. Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Ritual Sacrifice of Animals

The sacrifice of animals to various deities was quite common although not as frequent as Christians would later contend. It was generally limited to large official and formal religious ceremonies. Most everyday offerings were in the form of libations and fruits, seeds, and nuts and other plants. Nevertheless, an important animal sacrifice in ancient Rome was the “Suovetaurilia,” the offering of a Pig (sus), a Sheep (ovis), and a Bull (taurus) to the god Mars to bless and purify land around which boundaries the animals were led. Some ancient Greeks and Romans as well as modern scholars have theorized that animal sacrifice had its origin in human sacrifice to placate a deity in times of extreme danger such as during an earthquake, war, or famine. If this was so, it is unclear how and when it became more “commonplace” or when nonhuman animals were substituted for Human.

Ara Pacis, the “Altar of Peace,” is full of contradictions. It was built at the corner of Campus Martius, the Field of Mars, the god of War, to honor the goddess Pax (Peace) after the Roman Emperor Augustus’s conquest of Hispania and Gaul. At its inauguration in 9 BCE the customary Pig, Sheep, and Bull were led to their violent slaughter.

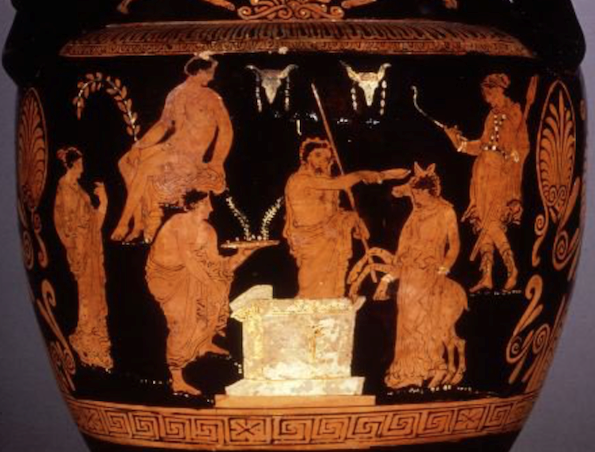

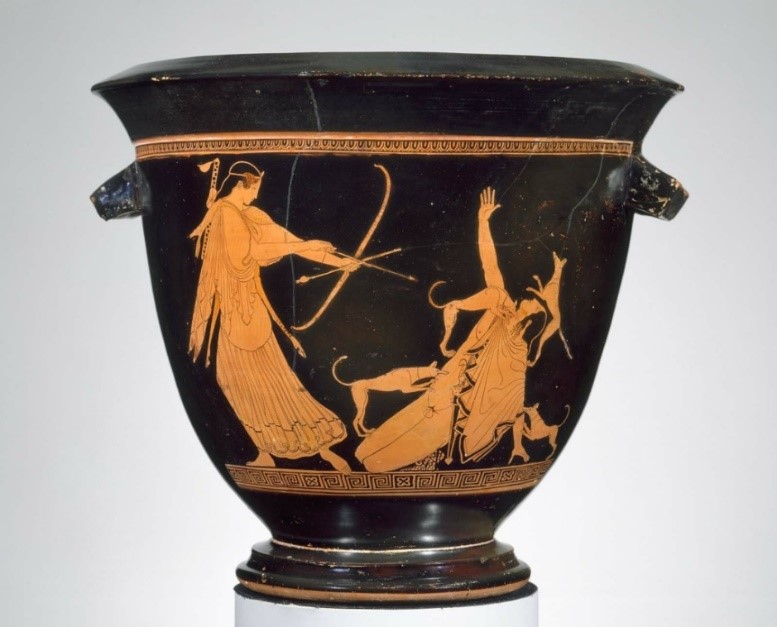

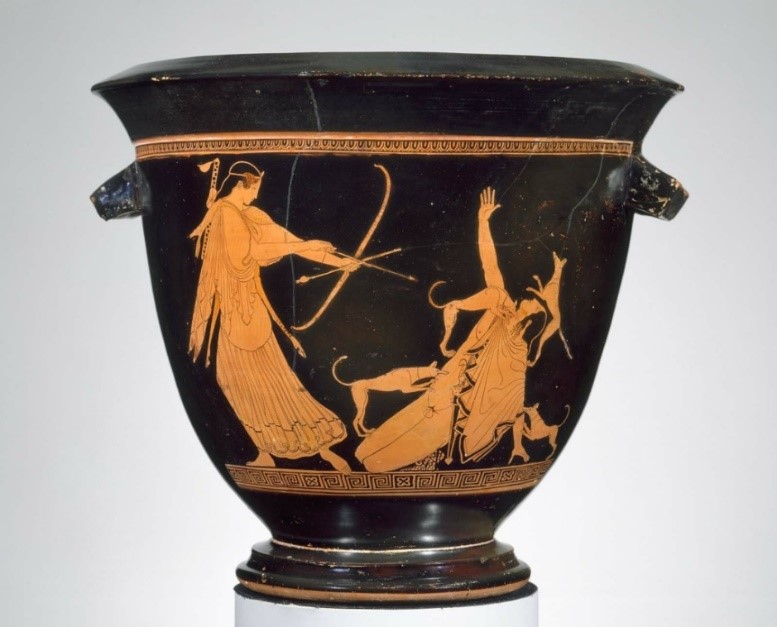

The most famous Human sacrifice in classical antiquity was that of the virgin Iphigenia, the daughter of Agamemnon, one of the Greek kings from the Trojan War. Although there are different versions of the ending, one of the most popular was told by the Greek playwright Euripides (ca. 480–ca. 406 BCE) who had the goddess Artemis, to whom the sacrifice had been offered in the first place, substitute the Human girl for a Deer, which perhaps could be interpreted as an allegory for an actual development from Human to animal sacrifice. There are many references to Human sacrifice in Greek literature and archaeological evidence pointing to such sacrifice has been unearthed in various places on Minoan-Mycenaean Crete (Myrtos, Knossos, Archanes, Chania) and at Etruscan Tarquinia.

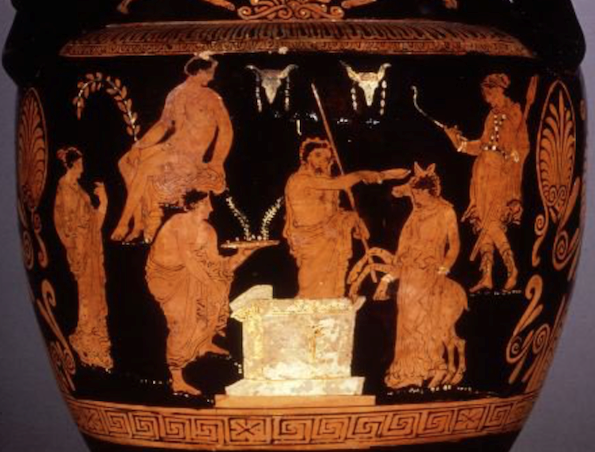

Iphigenia at the moment of substitution for a Deer. Volute crater, ca. 370-355 BCE. British Museum.

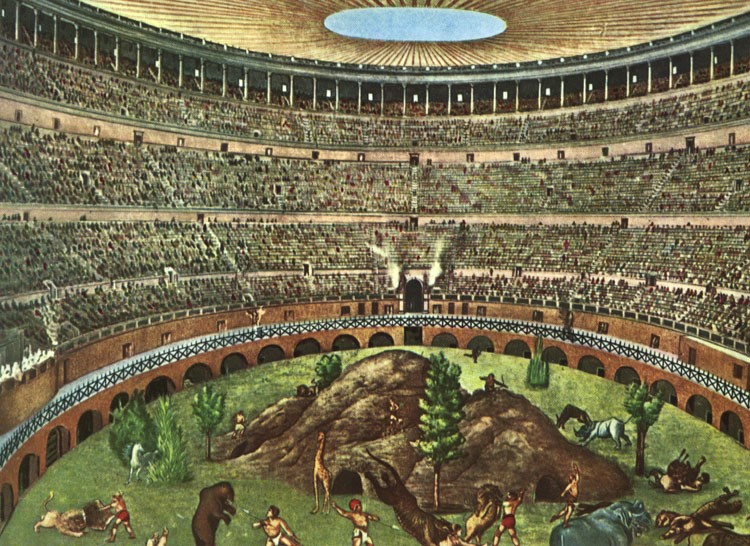

Animals as Entertainment

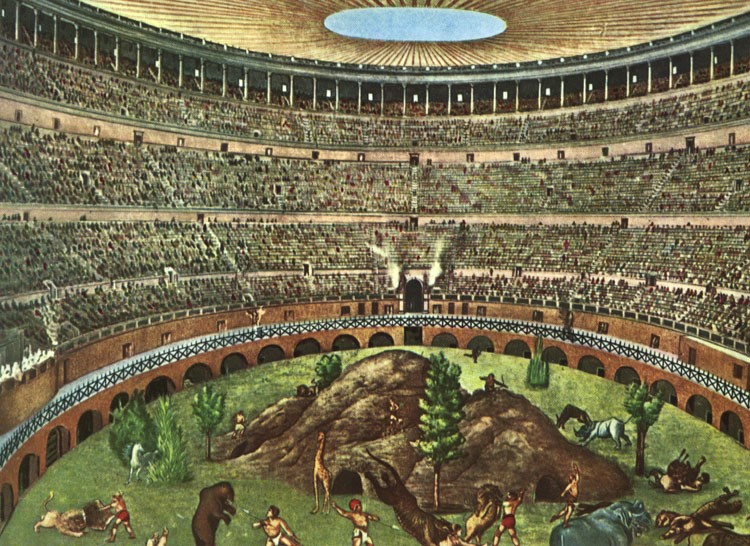

The Colosseum saw thousands of wild animals slaughtered. Lions, Tigers, Ostriches, Rhinoceroses, Buffaloes, Bison, Bulls, Bears, Wild Donkeys, Hippos, Giraffes, and Wild Boars were sent into the arena to fight each other, prisoners and gladiators, and also Christians. Roman philosopher and dramatist Seneca (ca. 4 BCE-65 CE) objected to the spectacle in one of his letters.

Letter from Seneca bemoaning the blood spectacle in the arena:

“…it is pure murder. The men have no defensive armor. They are exposed to blows at all points, and no one ever strikes in vain. Many persons prefer this program to the usual pairs and to the bouts “by request.” Of course they do; there is no helmet or shield to deflect the weapon. What is the need of defensive armor, or of skill? All these mean delaying death. In the morning they throw men to the lions and the bears; at noon, they throw them to the spectators. The spectators demand that the slayer shall face the man who is to slay him in his turn; and they always reserve the latest conqueror for another butchering. The outcome of every fight is death, and the means are fire and sword. This sort of thing goes on while the arena is empty” (Seneca, Letter to Lucilius 7).

Roman historian (of Greek origin and writing in Greek) Dio Cassius (ca. 155-235 CE) describes the slaughter of wild animals as theater:

Hippos, Rhinos, Elephants

“[Roman Emperor] Commodus devoted most of his life to ease and to horses and to combats of wild beasts and of men. In fact, besides all that he did in private, he often slew in public large numbers of men and of beasts as well. For example, all alone with his own hands, he dispatched five hippopotami together with two elephants on two successive days; and he also killed rhinoceroses and a camelopard” (Dio Cassius, Roman History 73.10.3).

200 Lions

“On his birthday he [Emperor Hadrian] gave the usual spectacle free to the people and slew many wild beasts, so that one hundred lions, for example, and a like number of lionesses fell on this single occasion” (Dio Cassius, Roman History 69.8.1).

500 Lions, 18 Elephants and human deception

“During these same days Pompey dedicated the theatre in which we take pride even at the present time. In it he provided an entertainment consisting of music and gymnastic contests and in the Circus a horse-race and the slaughter of many wild beasts of all kinds. Indeed, five hundred lions were used up in five days, and eighteen elephants fought against men in heavy armor. Some of these beasts were killed at the time and others a little later. For some of them, contrary to Pompey’s wish, were pitied by the people when, after being wounded and ceasing to fight, they walked about with their trunks raised toward heaven, lamenting so bitterly as to give rise to the report that they did so not by mere chance, but were crying out against the oaths in which they had trusted when they crossed over from Africa, and were calling upon Heaven to avenge them. For it is said that they would not set foot upon the ships before they received a pledge under oath from their drivers that they should suffer no harm” (Dio Cassius, Roman History 38).

700 wild Boars, Elephants, Hyena, Ostriches, Bison, Panthers, Wild Asses

“At these spectacles [10th anniversary of Emperor Severus’ power] sixty wild boars of Plautianus fought together at a signal and among many other wild beasts that were slain were an elephant and a corocotta [hyena]. This last animal is an Indian species, and was then introduced into Rome for the first time, so far as I am aware. It has the color of a lioness and tiger combined, and the general appearance of those animals, as also of a dog and a fox, curiously blended. The entire receptacle in the amphitheatre had been constructed so as to resemble a boat in shape, and was capable of receiving or discharging four hundred beasts at once; and then, as it suddenly fell apart, there came rushing forth bears, lionesses, panthers, lions, ostriches, wild asses, bisons (this is a kind of cattle foreign in species and appearance), so that seven hundred beasts in all, both wild and domesticated, at one and the same time were seen running about and were slaughtered” (Dio Cassius, Roman History 77).

Modern reconstruction of the “combats” between humans and animals at the Colosseum.

Mosaic featuring a Rhino in staged hunting “games” (venationes) at the arena. Piazza Armerina, Sicily, 4th century CE.

Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (ca. 96-30 BCE) tells the story of Alexander the Great administering a fight between Dogs and a Lion:

“To Alexander he presented many impressive gifts, among them one hundred and fifty dogs remarkable for their size and courage and other good qualities. People said that they had a strain of tiger blood. He wanted Alexander to test their mettle in action, and he brought into a ring a full grown lion and two of the poorest of the dogs. He set these on the lion, and when they were having a hard time of it he released two others to assist them. The four were getting the upper hand over the lion when Sopeithes sent in a man with a scimitar who hacked at the right leg of one of the dogs. At this Alexander shouted out indignantly and the guards rushed up and seized the arm of the Indian, but Sopeithes said that he would give him three other dogs for that one, and the handler, taking a firm grip on the leg, severed it slowly. The dog, in the meanwhile, uttered neither yelp nor whimper, but continued with his teeth clamped shut until, fainting with loss of blood, he died on top of the lion” (Diodorus Siculus 17.92).

Animals in War

Not only Horses were used in war, but also Elephants as famously witnessed by the Battle of Cannae in southeast Italy in 216 BCE between Carthage and Rome where the Carthaginian leader Hannibal won probably in no small measure due to his use of Elephants, a sight that terrified the Roman soldiers (and, no doubt, the Elephants, too).

Greek historian Polybius (ca. 200-118 BCE) describes the wading of a river in the Italian Alps by Elephants:

“The animals were always accustomed to obey their mahouts up to the water, but would never enter it on any account, and they now drove them along over the earth with two females in front, whom they obediently followed. As soon as they set foot on the last rafts the ropes which held these fast to the others were cut, and the boats pulling taut, the towing lines rapidly tugged away from the pile of earth the elephants and the rafts on which they stood. Hereupon the animals becoming very alarmed at first turned round and ran about in all directions, but as they were shut in on all sides by the stream they finally grew afraid and were compelled to keep quiet. In this manner, by continuing to attach two rafts to the end of the structure, they managed to get most of them over on these, but some were so frightened that they threw themselves into the river when halfway across. The mahouts of these were all drowned, but the elephants were saved, for owing to the power and length of their trunks they kept them above the water and breathed through them, at the same time spouting out any water that got into their mouths and so held out, most of them passing through the water on their feet” (Polybius 3.46).

A silver half shekel, probably featuring Hannibal and an Elephant, Carthage, 213-211 BCE.

Animals as Food

In ancient Greece, only animals sacrificed to the gods could be eaten after a portion of the animal was given to a particular deity or deities. The everyday staple foods of the ordinary Greek were mainly plant based. However, some Greeks objected to the eating of meat at all. Greek biographer and essayist Plutarch’s (46-120 CE) philosophical dialogue “On the Eating of Flesh” in a series of essays entitled Moralia makes a strong case for vegetarianism.

Greek essayist Plutarch’s (46-120 CE) case for vegetarianism:

“Can you really ask what reason Pythagoras had for abstaining from flesh? For my part I rather wonder both by what accident and in what state of soul or mind the first man who did so, touched his mouth to gore and brought his lips to the flesh of a dead creature, he who set forth tables of dead, stale bodies and ventured to call food and nourishment the parts that had a little before bellowed and cried, moved and lived. How could his eyes endure the slaughter when throats were slit and hides flayed and limbs torn from limb? How could his nose endure the stench?” (993a-b).

“When we had tasted and eaten acorns we danced for joy around some oak, calling it “life-giving” and “mother” and “nurse.” “…Why slander the earth by implying that she cannot support you?” (994f).

“Are you not ashamed to mingle domestic crops with blood and gore? You call serpents and panthers and lions savage, but you yourselves, by your own foul slaughters, leave them no room to outdo you in cruelty; for their slaughter is their living, yours is a mere appetizer” (994a-b).

“But nothing abashed us, not the flower-like tinting of the flesh, not the persuasiveness of the harmonious voice, not the cleanliness of their habits or the unusual intelligence that may be found in the poor wretches. No, for the sake of a little flesh we deprive them of sun, of light, of the duration of life to which they are entitled by birth and being. Then we go on to assume that when they utter cries and squeaks their speech is inarticulate, that they do not, begging for mercy, entreating, seeking justice…” (994e).

“What a terrible thing it is to look on when the tables of the rich are spread, men who employ cooks and spices to groom the dead! And it is even more terrible to look on when they are taken away, for more is left than has been eaten. So the animals died for nothing!” (994f).

“…it is absurd for them to say that the practice of flesh-eating is based on Nature. For that man is not naturally carnivorous is, in the first place, obvious from the structure of his body. A man’s frame is in no way similar to those creatures that were made for flesh-eating: he has no hooked beak or sharp nails or jagged teeth, no strong stomach or warmth of vital fluids able to digest and assimilate a heavy diet of flesh. It is from this very fact, the evenness of our teeth, the smallness of our mouths, the softness of our tongues, our possession of vital fluids too inert to digest meat that Nature disavows our eating of flesh” (994f-995a).

“If you declare that you are naturally designed for such a diet, then first kill for yourself what you want to eat. Do it, however, only through your own resources …just as wolves and bears and lions themselves slay what they eat, so you are to fell an ox with your fangs or a boar with your jaws, or tear a lamb or hare in bits. Fall upon it and eat it still living, as animals do” (995a-b).

“…Even when it is lifeless and dead, however, no one eats the flesh just as it is; men boil it and roast it, altering it by fire and drugs, recasting and diverting and smothering with countless condiments the taste of gore so that the palate may be deceived and accept what is foreign to it” (995b).

Another vegetarian was Pythagoras (ca. 570–495 BCE), the Greek philosopher and mathematician. Roman poet Ovid (43 BCE–17/18 CE) in his poem the Metamorphoses gave voice to his position on meat-eating. The passion of Ovid’s narrative makes it tempting to think that it reflects also his own sentiments on the subject. Moreover, the Metamorphoses contain many stories of Humans transformed into animals (and sometimes vice versa) such as Alcaeus into a Deer and Callisto into a Bear, often exhibiting empathy with the animal.

Roman poet Ovid (43 BCE-17/18 CE) on Pythagoras’s vegetarianism:

“He [Pythagoras] was the first to decry the placing of animal food upon our tables. His lips learned indeed but not believed in this, he was the first to open in such words as these:” (15.73-75)

“O mortals, do not pollute your bodies with a food so impious! You have the fruits of the earth, you have apples, bending down the branches with their weight, and grapes swelling to ripeness on the vines; you have also delicious herbs and vegetables…” (15.75-78).

“The earth, prodigal of her wealth, supplies you her kindly sustenance and offers you food without bloodshed and slaughter” (15.81-82).

”But that pristine age, which we have named the golden age” (15.96-97) “…All things were free from treacherous snares, fearing no guile and full of peace. But after someone, an ill exemplar, whoever he was, envied the food of lions, and thrust down flesh as food into his greedy stomach, he opened the way for crime” (15.102-103).

“Further impiety grew out of that, and it is thought that the sow was first condemned to death as a sacrificial victim because with her broad snout she had rooted up the planted seeds and cut off the season’s promised crop. The goat is held fit for sacrifice at the avenging altars because he had browsed the grape-vines” (15.111-115) “…But, ye sheep, what did you ever do to merit death, a peaceful flock…that bring us sweet milk to drink in your full udders, who give us your wool for soft clothing, and who help more by your life than by your death? What have the oxen done, those faithful, guileless beasts, harmless and simple, born to a life of toil?” (15.116-121) “Nor is it enough that we commit such infamy: they made the gods themselves partners of their crime and they affected to believe that the heavenly ones took pleasure in the blood of the toiling bullock! A victim without blemish and of perfect form (for beauty proves his bane), marked off with fillets and with gilded horns, is set before the altar, hears the priest’s prayer, not knowing what it means, watches the barley-meal sprinkled between his horns, barley which he himself labored to produce, and then, smitten to his death, he stains with his blood the knife which he has perchance already seen reflected in the clear pool. Straightway they tear his entrails from his living breast, view them with care, and seek to find revealed in them the purposes of heaven” (15.127-137) “…when you take the flesh of slaughtered cattle in your mouths, know and realize that you are devouring your own fellow-laborers” (15.141-142).

The Greek Neo-Platonic philosopher Porphyry (ca. 234-305 CE) on veganism:

“If…someone should…think it is unjust to destroy brutes, such a one should neither use milk, nor wool, nor sheep, nor honey. For, as you injure a man by taking from him his garments, thus, also, you injure a sheep by shearing it. For the wool which you take from it is its vestment. Milk, likewise, was not produced for you, but for the young of the animal that has it. The bee also collects honey as food for itself; which you, by taking away, administer for your own pleasure” (Porphyry, On Abstinence 1.21).

Animals as Companions/Pets

Companion animals or pets were popular also in antiquity, especially Dogs and Cats, but among the Egyptians also Baboons, various kinds of Monkeys, Fish, Gazelles, Birds, Lions, Mongoose, Hippos, etc., and among the Greeks and Romans, apart from Cats and Dogs also Rabbits, Snakes, Doves, Herons, Cranes, Chickens, Ducks, Geese, Magpies, Quails, Peacocks, Pigeons, Parrots, Nightingales, and other Birds, and, among wealthy Romans, possibly even Deer, Cheetahs, Leopards, and Lions.

Dogs

Probably the most famous Dog in ancient Greece was Argus, the loyal and faithful Dog that recognizes his disguised guardian, the long-lost Greek hero from the Trojan War, Odysseus, in the Homeric epic the Odyssey (8th century BCE) whereupon he dies. Knowing that his guardian was alive and well after being gone for some twenty years allowed the ailing and aged Dog Argus to finally give up the ghost.

Legendary Greek poet Homer (8th century BCE) tells the story about the Dog Argus:

“There lay the dog Argus, full of dog ticks. But now, when he became aware that Odysseus was near, he wagged his tail and dropped both ears, but nearer to his master he had no longer strength to move. Then Odysseus looked aside and wiped away a tear, easily hiding from Eumaeus what he did; and immediately he questioned him, and said:

Eumaeus, truly it is strange that this dog lies here in the dung. He is fine of form, but I do not clearly know whether he had speed of foot to match this beauty or whether he is merely as table dogs are, which their masters keep for show.”

“To him then, swineherd Eumaeus, did you make answer and say: “Yes, truly this is the dog of a man who has died in a far land. If he were but in form and action such as he was when Odysseus left him and went to Troy, you would soon be amazed at seeing his speed and his strength…” (Homer, Odyssey 17. 290-327).

“…But as for Argus, the fate of black death seized him once he had seen Odysseus in the twentieth year” (Homer, Odyssey 17. 326-27).

The Dog Argus on a silver denarius, 82 BCE. This image of a young and energetic Argus does not correspond well with the portrait of the old and sick Dog from the Odyssey. Photo by Mike Braunlin.

Roman author (writing in Greek, the lingua Franca of Rome) Aelian (ca. 175-235 CE), too, wrote about the loyalty of Dogs:

A faithful Dog recognizes its guardian’s murderers

“Pyrrhus of Epirus was on a journey when he came upon the corpse of a man who had been killed, with his Dog standing beside and guarding its master to prevent anybody from adding outrage to murder. Now it happened that this was the third day for which the Dog was keeping its assiduous and most patient watch, unfed. And so when Pyrrhus learnt this he took pity on the dead man and ordered him to be buried; but as for the Dog, he directed that it should be cared for and gave it whatever one offers a dog with one’s hand, in sufficient quantity and of a nature to induce it to be friendly and well-disposed towards him; and little by little Pyrrhus drew the Dog away. So much then for that. Now not so long after, there was a review of the hoplites, and the King whom I mentioned above was looking on, and that same Dog was at his side. For most of the time it remained silent and completely gentle. But directly it saw the murderers of its master in the review, it could not contain itself or remain where it was, but leaped upon them, barking and tearing them with its claws, and by frequently turning towards Pyrrhus did its best to make him see that it had caught the murderers. And so a suspicion dawned upon the King and those about him, and the way in which the Dog barked at the aforesaid men caused them to reflect. The men were seized and put on the rack and confessed their crime” (Aelian, On the Nature of Animals 7.10).

Aelian further described how Dogs were quite often rewarded for their loyalty by having their portraits painted as in the case of a Dog accompanying its guardian to war.

“Their hounds used to accompany the people to war, and in fact these allies were an advantage and a help to them. An Athenian took with him a Dog as fellow-soldier to the battle of Marathon, and both are figured in a painting in the Stoa Poecile, nor was the Dog denied honor but received the reward of the danger it had undergone in being seen among the companions of Cynegirus, Epizelus, and Callimachus. They and the Dog were painted by Micon, though some say it was not his work but that of Polygnotus of Thasos” (Aelian, On the Nature of Animals 7.38).

Women were frequently the butt of jokes of the Roman satirist Juvenal (first-early second century CE). Here he may have captured “a grain of truth.” During the so called second wave feminism in the 1970s and early 1980s some women wore buttons and t-shirts that read: “The more I learn about men, the more I appreciate my dog.” This humorous motto may already have been embraced by Roman women in Juvenal’s day.

Roman satirist Juvenal (1st-early 2nd century CE) on women preferring Dogs to men:

“The woman I cannot stand is the one who calculatingly commits an enormous crime in full command of her senses. They watch Alcestis endure her husband’s death and if a similar swap were offered to them, they’d happily see their husbands die to save their puppy’s life” (Juvenal, Satire 6.653-4).

“Courtier” Petronius’s “Cena Trimalchionis” (written during the reign of Emperor Nero) forms part of a larger novel, Satyricon. This satire describes the excesses and vulgarities of wealthy Romans and how pet Dogs were status symbols among the wealthy.

Roman “courtier” and writer Petronius (ca. 27-66 CE) recounts the story of Trimalchio and his Dogs:

“Trimalchio himself also, after imitating a man with a trumpet, looked round for his favorite, whom he called Croesus. The creature had blear eyes and very bad teeth, and was tying up an unnaturally obese black puppy in a green handkerchief, and then putting a broken piece of bread on a chair, and cramming it down the throat of the dog that did not want it and felt sick. This reminded Trimalchio of his duties, and he ordered them to bring in Scylax,” the guardian of the house and the slaves.” An enormous dog on a chain was at once led in, and on receiving a kick from the porter as a hint to lie down, he curled up in front of the table. Then Trimalchio threw him a bit of white bread and said, “No one in my house loves me better than Scylax.” The favorite took offence at his lavish praise of the dog, and put down the puppy, and encouraged her to attack at once. Scylax, after the manner of dogs, of course, filled the dining-room with a most hideous barking, and nearly tore Croesus’s little Pearl to pieces” (Petronius, Satyricon 64).

Trimalchio commanded that his Dog be carved on his tomb at the feet of his statue, and, on his right, an effigy of his beloved wife Fortunata holding a Dove in her hand and leading her Puppy on a leash.

“Fortunata holding a dove, and let her be leading a little dog with a waistband [leash] on” (Petronius. Satyricon 71).

Pet Burials and Epitaphs

Pet burials with tomb stones were not uncommon, especially in Rome where, for example, a tombstone with a sculpted Dog holds an epitaph to a Dog named Helena, dated to 150-200 CE, now at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles. The Latin inscription reads: “To Helena, foster daughter, incomparable and trustworthy soul.”

We read that an Athenian named Poliarch was so attached to his pets that if a pet Dog or Rooster died, he held public funerals to which his friends were invited, and he had inscribed tombstones erected to them.

“They say that Poliarchus the Athenian arrived at so great a height of Luxury, that he caused those Dogs and Cocks which he had loved, being dead, to be carried out solemnly, and invited friends to their Funerals, and buried them splendidly, erecting Columns over them, on which were engraved Epitaphs” (Aelian, Various Histories 8.4).

Just like today’s homeowners, the ancients also used dogs for protection. This mosaic from Pompeii depicts a chained guard dog with the inscription Cave Canem (Be Aware of the Dog), terminus ante quem 79 CE.

Probably the saddest but also most famous image of a Dog from antiquity is the guard Dog who because it was chained could not escape the ashes of the volcanic eruption of Vesuvius that buried the town of Pompeii in 79 CE and so died in agony.

Cats

Cats are generally believed to have been domesticated in ancient Egypt some 4,000 years ago; however, evidence suggests that the Cat may have been part of the household in the Near East already some 14,000 years ago along with Sheep, Goats, and Dogs.

The so called Gayer-Anderson Cat (the Cat goddess Bastet) from Ancient Egypt, Late Period ca. 664-332 BCE. Made of bronze with gold ornaments. British Museum.

The Lion goddess Sekhmet, ca. 1390-1352 BCE. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Sekhmet, the Lion Goddess. 19th Dynasty, 1350-1205 BCE. Made of black granite. Cincinnati Art Museum.

Egyptian Cat goddess Bastet, ca. 664-30 BCE. Made of leaded bronze. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

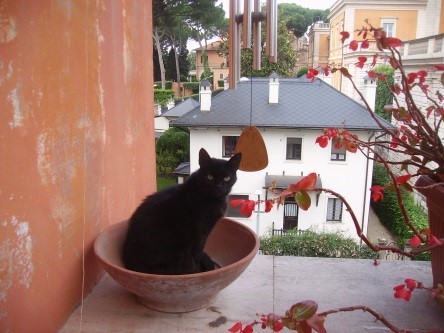

Cats and Lions were sacred in ancient Egypt. There was even a Cat goddess, Bastet. They were used both as pets and mousers. Many Cat owners had their Cats mummified to accompany them in death, although mummified Cats and Cat figurines were mostly given as offerings to the immensely popular Cat goddess at her temple in Bubastis (Tell Basta), where amulets and votive figurines of the goddess were mass produced and festivals with wine, song and dance in her honor were held.

Greek historian Herodotus (ca. 484-425 BCE) on the festival of the Cat goddess:

“…when they have reached Bubastis, they make a festival with great sacrifices, and more wine is drunk at this feast than in the whole year beside. Men and women (but not children) are wont to assemble there to the number of seven hundred thousand, as the people of the place say” (Herodotus 2.60).

The Ancient Egyptians believed in life after death. Literally, thousands of Cat mummies have been excavated in Egypt. However, many also felt bad about killing Cats for mummification so most of the many Cat mummies found in Egyptian tombs and temples are actually fake. In fact, the penalty for killing a Cat in Egypt, even by accident, was death. The export of Cats from Egypt was so strictly prohibited that government agents were dispatched to other lands to find and return Cats which had been smuggled out. This speaks to the extraordinary high regard for Cats in ancient Egypt.

Diodorus Siculus on embalming Cats:

“When one of these animals dies they wrap it in fine linen and then, wailing and beating their breasts, carry it off to be embalmed; and after it has been treated with cedar oil and such spices as have the quality of imparting a pleasant odor and of preserving the body for a long time, they lay it away in a consecrated tomb” (1.83.5-6).

Numerous Cat mummies were found in the desert at Beni Hassan, about a hundred miles from Cairo in the late 1800s. Unfortunately, most were sold on the private antiquities market.

The death penalty for killing a Cat

“And whoever intentionally kills one of these animals is put to death, unless it be a cat or an ibis that he kills; if he kills one of these [cats], whether intentionally or unintentionally, he is certainly put to death, for the common people gather in crowds and deal with the perpetrator most cruelly, sometimes doing this without waiting for a trial. And because of their fear of such a punishment any who have caught sight of one of these animals lying dead withdraw to a great distance and shout with lamentations and protestations that they found the animal already dead. So deeply implanted also in the hearts of the common people is their superstitious regard for these animals and so unalterable are the emotions cherished by every man regarding the honor due to them that once, at the time when Ptolemy their king had not as yet been given by the Romans the appellation of “friend” and the people were exercising all zeal in courting the favor of the embassy from Italy which was then visiting Egypt and, in their fear, were intent upon giving no cause for complaint or war, when one of the Romans killed a cat and the multitude rushed in a crowd to his house, neither the officials sent by the king to beg the man off nor the fear of Rome which all the people felt were enough to save the man from punishment, even though his act had been an accident. And this incident we relate, not from hearsay, but we saw it with our own eyes on the occasion of the visit we made to Egypt” (Diodorus Siculus 1.83.1-8).

A telling and frightening story is that of the Persian army led by Cambyses II at the Battle of Pelusium in 525 BCE.

The Persians used the Egyptian veneration for Cats and other animals against them by in addition to painting Cats on their shields, also placing Dogs, Sheep, Ibises, and especially Cats in the front lines of the battle configuration which prevented the Egyptians from defending themselves because of their concern for the animals’ safety, which ultimately led to Egypt being conquered.

Greek historian Herodotus, writing about the Egyptian veneration for Cats, explains that when a Cat dies a natural death, all who dwell in the house of that Cat shave their eyebrows to express their sorrow. The time of mourning ends only when the eyebrows grow back.

Herodotus on mourning Cat:

“And when a fire breaks out very strange things happen to the cats. The Egyptians stand round in a broken line, thinking more of the cats than of quenching the burning; but the cats slip through or leap over the men and spring into the fire. When this happens, there is great mourning in Egypt. Dwellers in a house where a cat has died a natural death shave their eyebrows and no more; where a dog has so died, the head and the whole body are shaven” (Herodotus 2.66-2.67).

“Dead cats are taken away into sacred buildings, where they are embalmed and buried, in the town of Bubastis; bitches are buried in sacred coffins by the townsmen, in their several towns; and the like is done with ichneumons. Shrewmice and hawks are taken away to Buto, ibises to the city of Hermes. There are but few bears, and the wolves are little bigger than foxes; both these are buried wherever they are found lying” (Herodotus 2.67).

Mother Cat and Kittens on a faience ring from Egypt, ca. 1295–664 BCE. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The relationship of the Ancient Greeks (as of today’s Greeks) to the Cat was ambivalent at best. They were hated and loved. Aristophanes, the ancient Greek comedy playwright, often featured Cats which the characters jokingly blamed for everything. It was not until the ancient Romans (much like today’s Romans) that the Cat’s position was again elevated, not to quite the same level as in ancient Egypt, but as pets and useful mousers.

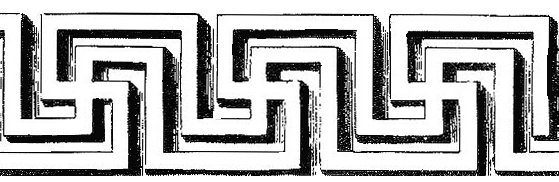

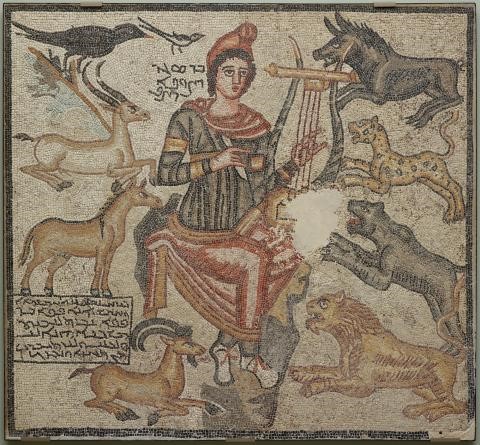

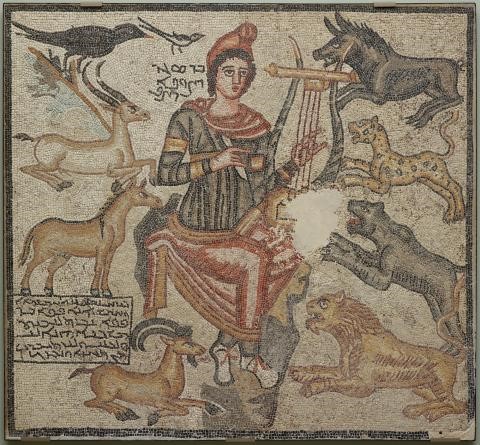

There are several ancient descriptions of animals being enticed by ancient music. The story of the legendary poet and prophet from Thrace (today bordering Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey), Orpheus, and the many wild animals that came to listen to him playing the lyre (made from Turtles’ shells) was popular already in antiquity.

“Orpheus Taming Wild Animals.” Mosaic. Eastern Roman Empire, near Edessa. 194 CE. Dallas Museum of Art.

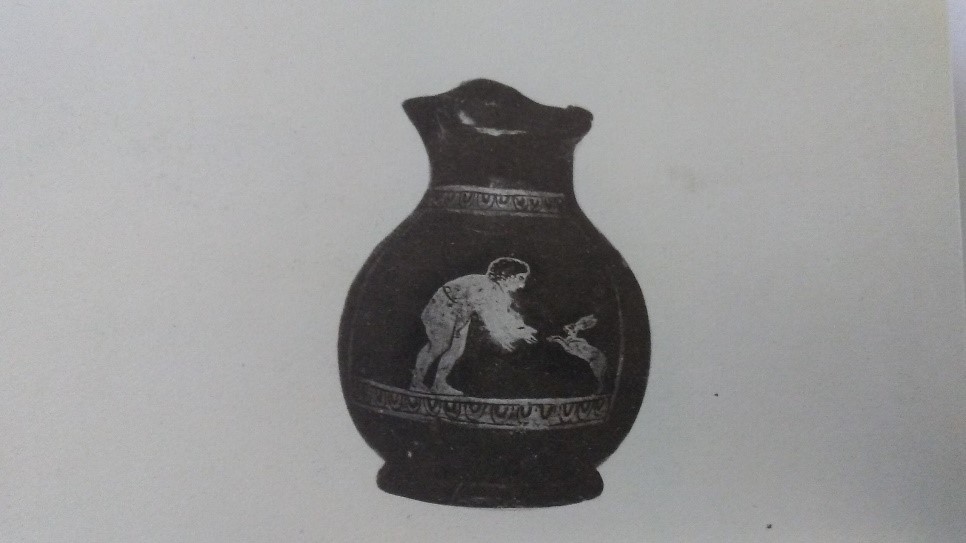

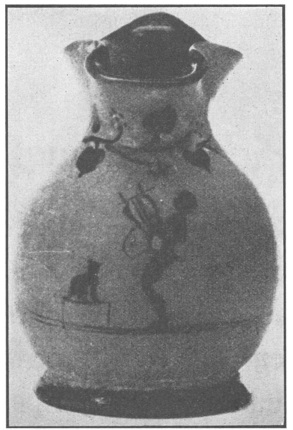

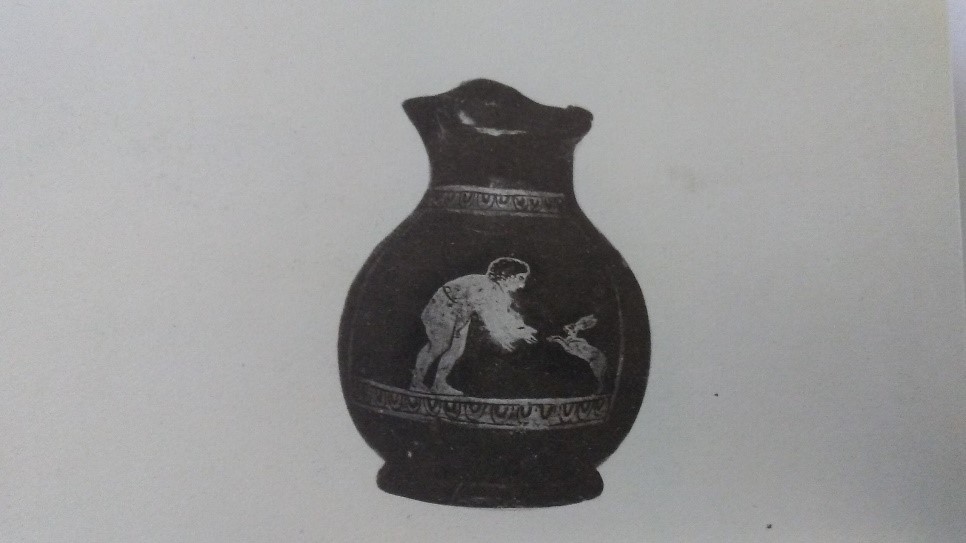

On a Boeotian toy oinochoe a boy plays the lyre for the amusement of his Cat that sits on a small stool and listens attentively. Antikensammlung, Berlin.

More recent Cat lovers

Other purported Cat lovers include Islam’s founder Mohammed who supposedly cut off his sleeve on which a Cat was sleeping rather than disturbing it when called to prayer, Queen Victoria whose Persian Cats were members of her court, and the former Pope Benedict XVI who allegedly feeds stray Cats around his house at the Vatican. Pope Benedict’s successor Pope Francis on the other hand, notwithstanding that he took his papal name from Saint Francis who believed that all animal species, Human and non-Human, were equal and all God’s creatures, expressed his objection to women who care for Cats and Dogs instead of having Human children, a rather false dichotomy since one does not prevent the other, and not unlike Greek church father Clement of Alexandria’s (ca. 150-215 CE) rebuke of pet keeping instead of caring for poor people which, according to him, were incompatible concerns. The street Cat (and Dog) in contemporary Greece and the area which in antiquity was known as Magna Graecia (southern Italy and Sicily), because of its many Greek colonies, still does not fare well to this day. Many people view Cats as vermin and put out poison to kill them. Unfortunately, the Cat did not do well during the European Middle Ages either. The Cat, especially the black Cat, was considered demonic and was killed along with the people, mostly older women labeled witches, who cared for them. Pope Gregory IX (1227-1241) issued a papal bull condemning the Cat as evil which prompted the mass killing of them all over Europe. Not unlike the often ill-informed current pronouncements against Rats, Pigeons, and Cockroaches, the Cat’s teeth were considered venomous, its flesh poisonous, and its hair lethal causing suffocation if even a few hairs were to be accidentally swallowed. Today’s Roman gattara (“street cat lady”), however, carries the witch label with pride.

Other Companion Animals

Snakes

“As a drinking and living companion he [Ajax] had a tame snake that was five cubits long, which led the way when he traveled and otherwise followed him like a dog” (Philostratus, Heroicus 31.3).

Hares/Rabbits

Roman politician and writer Julius Caesar (100-March 15, 44 BCE) tells us that the Britanni (ancestors of the English) did not eat Hare, Goose, or Chicken and instead raised these animals for pleasure.

“They account it wrong to eat hare, fowl, and goose; but these they keep for pastime or pleasure” (Caesar, Gallic Wars 5.2).

A boy, wearing a band of amulets around his body, holds out his arms to a Hare which is standing on its hind legs to greet its guardian. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

Fishes [sic]

Fishes as pets are described by Aelian:

“It seems that even Fishes are both tame and tractable, and when summoned can hear and are ready to accept food that is given them, like the sacred eel in the Fountain of Arethusa. And men tell of the moray belonging to Crassus the Roman, which had been adorned with earrings and small necklaces set with jewels, just like some lovely maiden; and when Crassus called it, it would recognize his voice and come swimming up, and whatever he offered it, it would eagerly and promptly take and eat. Now when this fish died Crassus, so I am told, actually mourned for it and buried it. And on one occasion when Domitius said to him ‘You fool, mourning for a dead moray!’ Crassus took him up with these words: ‘I mourned for a moray, but you never mourned for the three wives you buried” (Aelian, On the Nature of Animals 8.4[i]).

“Tame fishes which answer to a call and gladly fish of various lands accept food are to be found and are kept in many places, in Epirus for instance, at the town, formerly called Stephanepolis, in the temple of Fortune in the cisterns on either side of the ascent; at Helorus too in Sicily which was once a Syracusan fortress; and at the shrine of Zeus of Labranda in a spring of transparent water. And there fish have golden necklaces and earrings also of gold…And in Chios in what is called ‘The Old Men’s Harbor’ there are multitudes of tame fish, which the inhabitants of Chios keep to solace the declining years of the very aged” (Aelian, On the Nature of Animals 12.30).

Pigeons

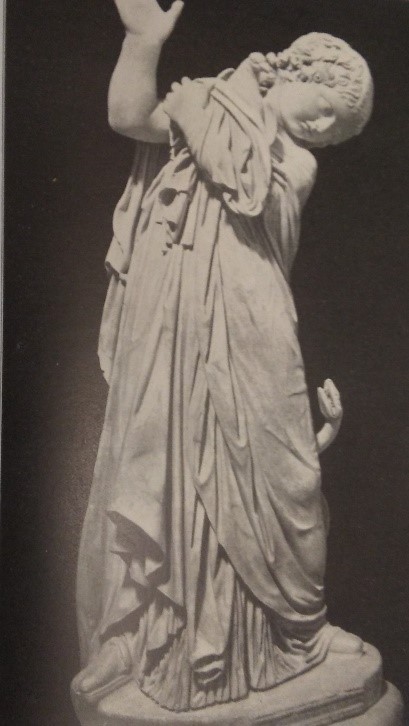

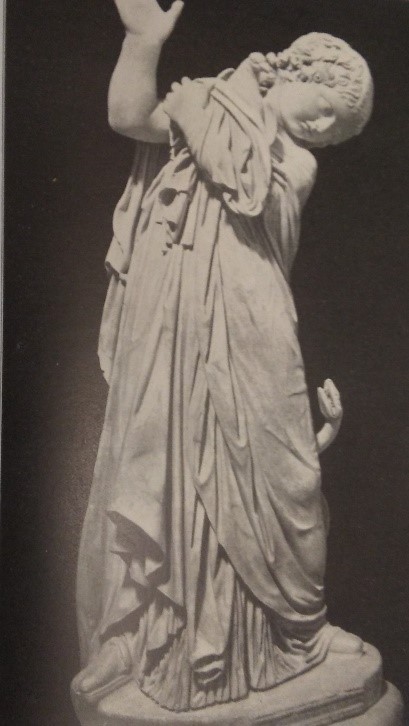

This Greek life-size Hellenistic marble statue features a young girl holding her pet Pigeon far away from her pet Snake to protect it. The sculptor makes it clear that the girl just discovered her pet Snake’s intentions. Capitoline Museums, Rome.

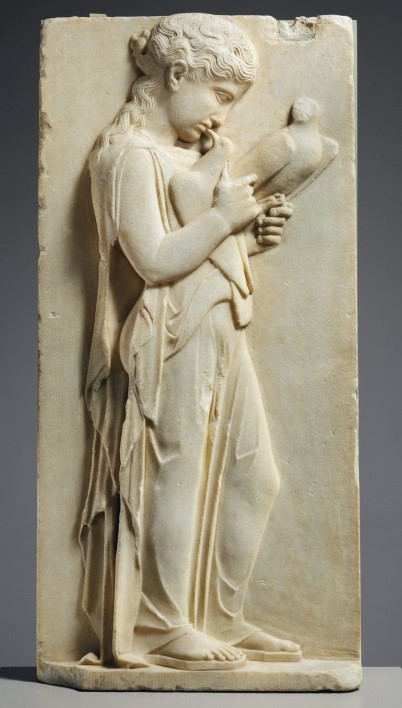

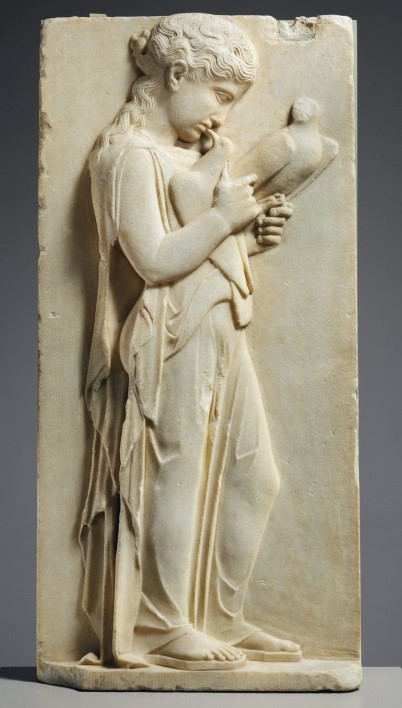

A famous Greek marble stele at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York features a girl kissing her pet Pigeon, ca. 450-440 BCE.

Sparrows

The Roman poet Catullus’s (ca. 84-54 BCE) poems about the heroine Lesbia’s Sparrow and its death are some of the most admired from classical antiquity (poems 2 and 3):

“Sparrow, my lady’s pet, with whom she often plays whilst she holds you in her lap, or gives you her fingertip to peck and provokes you to bite sharply, whenever she, the bright-shining lady of my love, has a mind for some sweet pretty play, in hope, as I think, that when the sharper smart of love abates, she may find some small relief from her pain—ah, might I but play with you as she does, and lighten the gloomy cares of my heart! This is as welcome to me as to the swift maiden was (they say) the golden apple, which loosed her girdle too long tied.”

“Mourn, ye Graces and Loves, and all you whom the Graces love. My lady’s sparrow is dead, the sparrow my lady’s pet, whom she loved more than her very eyes; for honey-sweet he was, and knew his mistress as well as a girl knows her own mother. Nor would he stir from her lap, but hopping now here, now there, would still chirp to his mistress alone. Now he goes along the dark road, thither whence they say no one returns. But curse upon you, cursed shades of Orcus, which devour all pretty things! Such a pretty sparrow you have taken away. Ah, cruel! Ah, poor little bird! All because of you my lady’s darling eyes are heavy and red with weeping.”

Ravens

Well-known is the story of the cobbler’s pet Raven, as recorded by Roman author Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE). This Raven greeted Roman Emperor Tiberius every morning, and became a public favorite. It was buried with much pomp and circumstance by the Roman populace.

“When Tiberius was emperor, a young raven from a brood hatched on the top of the Temple of Castor and Pollux flew down to a cobbler’s shop in the vicinity, being also commended to the master of the establishment by religion. It soon picked up the habit of talking, and every morning used to fly off to the Platform that faces the forum and salute Tiberius and then Germanicus and Drusus Caesar by name, and next the Roman public passing by, afterwards returning to the shop; and it became remarkable by several citizens, in the city in which many leading men had had no obsequies at all, while the death of Scipio Aemilianus after he had destroyed Carthage and Numantia had not been avenged by a single person. The date of this was 28 March, a.d. 36, in the consulship of Marcus Servilius and Gaius Cestius years’ constant performance of this function. This bird the tenant of the next cobbler’s shop killed, whether because of his neighbor’s competition or in a sudden outburst of anger, as he tried to make out, because some dirt had fallen on his stock of shoes from its droppings; this caused such a disturbance among the public that the man was first driven out of the district and later actually made away with, and the bird’s funeral was celebrated with a vast crowd of followers, the draped bier being carried on the shoulders of two Ethiopians and in front of it going in procession a flute-player and all kinds of wreaths right to the pyre, which had been erected on the right hand side of the Appian Road at the second milestone on the ground called Rediculus’s Plain. So adequate a justification did the Roman nation consider a bird’s cleverness to be for a funeral procession and for the punishment of a Roman” (Pliny, Natural History 10.60).

Animals as Gifts in Courtship

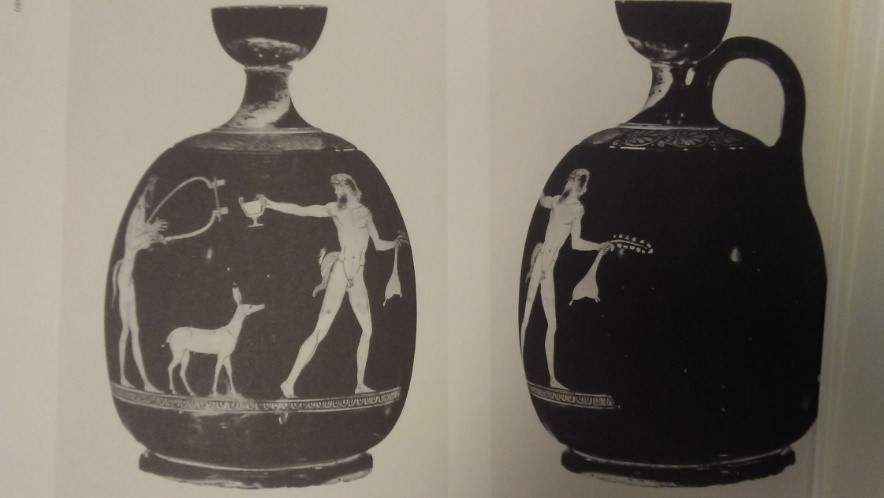

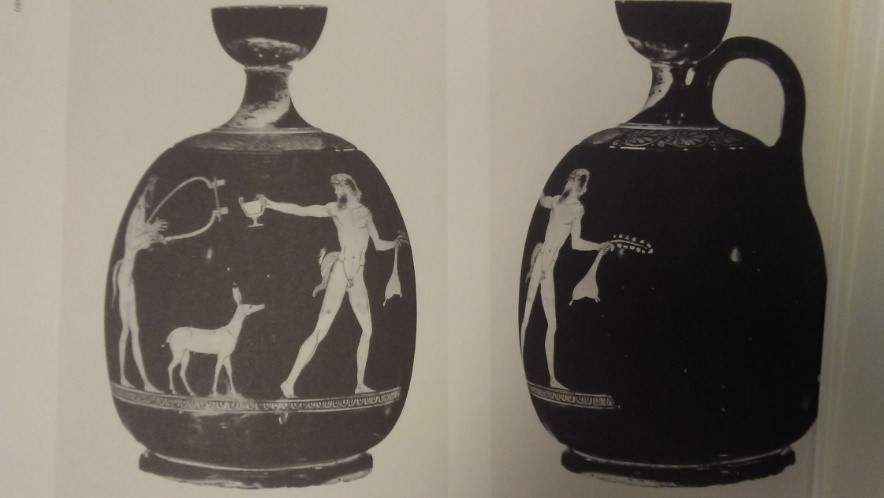

Animals such as Hares and Rabbits, Fawns, Doves, Dogs, Roosters were given in courtship as often depicted in Greek art whether the couples were mythological creatures or real, whether of the same or opposite sex.

Attic red-figure skyphos (wine cup), ca. 460-450 BCE. The Louvre Painter. Antikensammlung, Berlin.

Attic red-figure pelike (liquid container), ca 450-400 BCE. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

Same sex love in antiquity was (and still is) not just a thing among Human animals.

Wild Animals

Foxes

Foxes were wild and often considered a nuisance for wine growers because they liked eating the vines. Chickens were not kept as often in antiquity as now, so we do not hear much about Foxes killing Chickens.

Greek biographer and essayist Plutarch (ca. 46-120 CE) tells of a Spartan boy who stole a young Fox and concealed it under his garments. The Fox bit the boy who, out of fear of being discovered, quietly endured the pain and died:

“The boys make such a serious matter of their stealing, that one of them, as the story goes, who was carrying concealed under his cloak a young fox which he had stolen, suffered the animal to tear out his bowels with its teeth and claws, and died rather than have his theft detected” (Plutarch, Lycurgus 18.51).

Children in Sparta, during rites of passage ceremonies, fasted almost to the point of starvation and were supposed to steal to fill their bellies. It is probably no coincidence that during this phase of the ceremonies at the Artemis Orthia sanctuary in Sparta, the children were referred to as Foxes. At other Greek temples dedicated to Artemis girls (possibly boys, too) in rites of passage rituals were called Bears and Fawns, and the priestesses in the Artemis Temple at Ephesus Bees and the priests Drones. Artemis was the Greek goddess of animals, especially wild, and of all of nature.

Terracotta figurine of a Fox scratching its head. Tanagra, Greece, ca. 5th century BCE. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

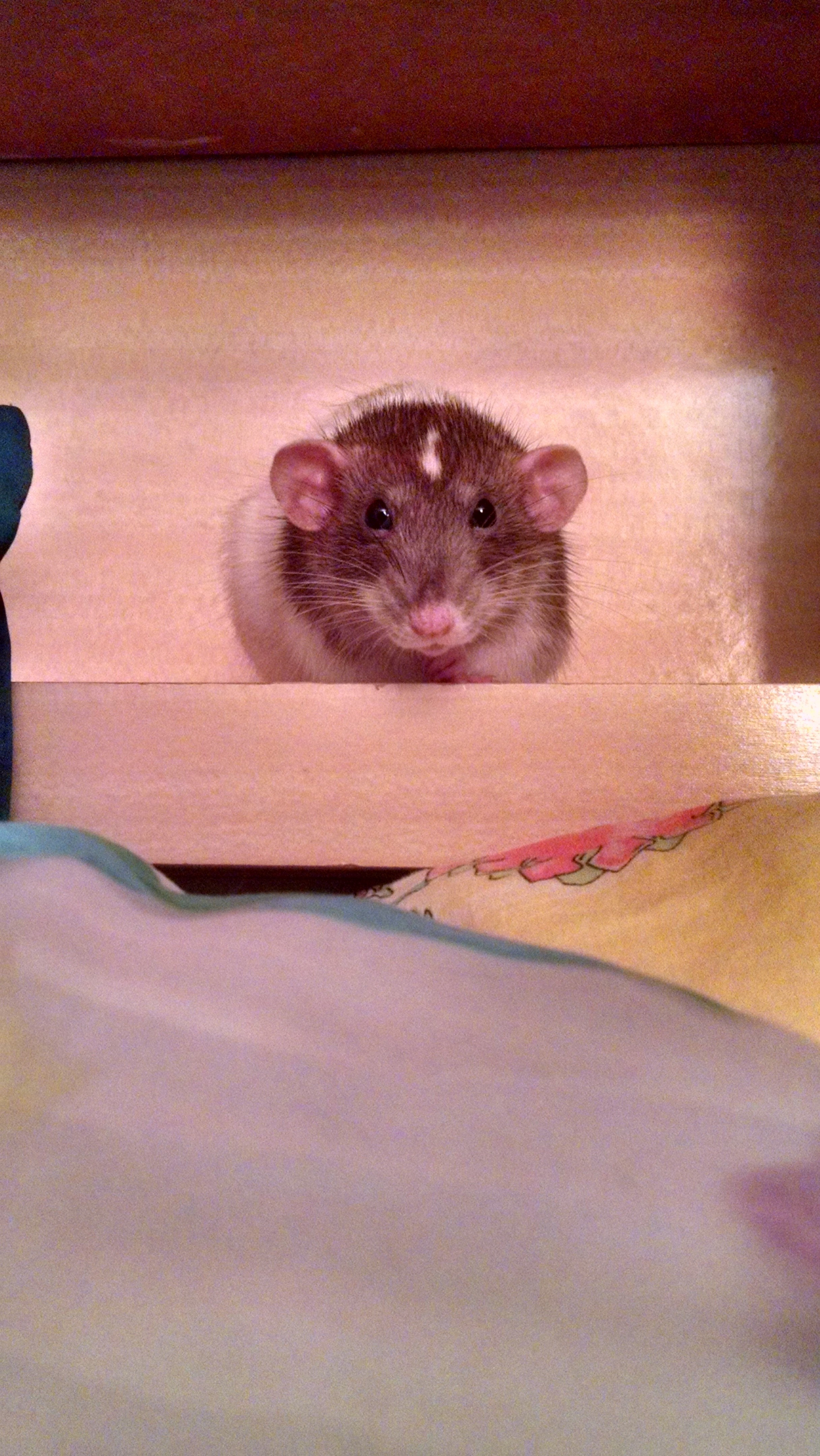

Rats and Mice

Rats and mice were considered pests also in antiquity and were even eaten; however, as with everything in antiquity related to animals, there were contradictions. Mice were also worshiped as the sacred animal of the god Apollo Smintheus, the Mouse-God; his cult statues showed him with a mouse and a mouse is also featured on the coins of the town of Hamaxitus in the Troad in modern Turkey where Apollo Smintheus’s main temple was situated.

Greek historian and geographer Strabo (ca. 64/63 BCE-24 CE) on the temple of Apollo the Mouse-God:

“In this Chrysa is also the temple of Sminthian the symbol which preserves the etymology of the name, Ι mean the mouse, lies beneath the foot of his image. These are the works of Scopas of Paros; and also the history, or myth, about the mice is associated with this place: When the Teucrians arrived from Crete (Callinus the elegiac poet was the first to hand down an account of these people, and many have followed him), they had an oracle which bade them to “stay on the spot where the earth-born should attack them”; and, he says, the attack took place round Hamaxitus, for by night a great multitude of field-mice swarmed out of the ground and ate up all the leather in their arms and equipment; and the Teucrians remained there; and it was they who gave its name to Mt, Ida, naming it after the mountain in Crete. Heracleides of Pontus says that the mice which swarmed round the temple were regarded as sacred, and that for this reason the image was designed with its foot upon the mouse” (Strabo, Geography 13.1.48).

Mice lived and were fed at public expense in Apollo Smintheus’s temples. Herodotus tells a story in which the Pharaoh Sethos was saved from an Assyrian invading army when a group of Mice ate their shield-handles, bowstrings, and quivers overnight (Herodotus 2.141).

According to Pliny the white Mouse was a good omen in Rome:

“The Public Records relate that during the siege of Casilinum by Hannibal a mouse was sold for 200 francs, and that the man who sold it died of hunger while the buyer lived. The appearance of white mice constitutes a joyful omen” (Pliny, Natural History 8.222-8.223).

Bronze figurine of a Mouse dedicated to Apollo Smintheus (the Mouse God). (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin) Antikensammlung, Berlin.

The Rat is worshiped in today’s India where thousands of Rats live and are fed in the Temple of Karni Mata at Deshnoke in Rajasthan. Sacred Rats and Mice have also been found in tombs of women from Neolithic Çatal Höyük in present-day Turkey to female warrior graves in Southern Russia.

Deer

Deer were hunted then as now for “sport” or rather for “tests of manhood.” However, just like in the Harry Potter book series, the gentle deer were also sacred; in antiquity as the special companions of the goddess Artemis/Diana, but also as gods in their own right among the Celts and other ancient peoples.

Artemis and a Stag. Roman copy of a sculpture by Greek artist Leochares from ca. 325 BCE. Louvre.

Artemis’/Diana’s Deer on a Roman billon Antoninianus, from the reign of Emperor Gallienus, ca. 267/268 CE. DIANAE CONSERVATORI AVGVSTI (to Diana (Artemis), the Preserver of the Emperor). Photo by Mike Braunlin.

A Scythian fibula (brooch) in the shape of a Deer. Northern Caucasus. Made of gold, late 7th century BCE. Hermitage, Saint Petersburg.

Deer (the Doe), the “Patronus” of Harry Potter and Professor Snape.

The Pastime of Hunting

Of the story about Alcaeus, there are many versions. A children’s cartoon on American TV a couple of years ago featured the story of the goddess Artemis and the hunter Actaeon, loosely based on Ovid’s tale in the Metamorphoses. This version described how the Greek goddess Artemis transformed the hunter Actaeon into a Stag to teach him a lesson about not killing animals. The terrified Actaeon, now a Deer, attempts to speak but is not able to make himself understood without a human language. As his hunting companions are poised to throw their spears and shoot their arrows and the hunting Dogs are about to pounce at the “Deer” Actaeon, he promises Artemis that if she would only change him back into human form, he would never kill another living being and instead educate his hunting companions about the plight and suffering of hunted animals, which was indeed the happy outcome.

Artemis shooting at Actaeon with his own hunting Dogs attacking, seeing him as a Deer. Bell krater to mix water and wine by the so called Pan Painter, ca. 470 BCE. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Wild Boars, too, were hunted, especially among the Etruscans. However, hunting in classical Greece seems mostly to have been an activity among upper class young males for “sport” or “proof of manhood” rather than among farmers or workers for food, so the number of animals hunted in antiquity would have been smaller than today.

Etruscan perfume bottle in the figure of a Boar, ca. 600-500 BCE. Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio.

On the Emotions of Animals

The profound sadness some animals feel at the loss of a friend was nicely captured by Aelian:

“Now the Purple Coot, in addition to being extremely jealous, has, I believe, this peculiarity; they say that it is devoted to its own kin and loves the company of its mates. At any rate I have heard that a Purple Coot and a Cock were reared in the same house that they fed together, that they walked step for step, and that they dusted in the same spot. From these causes there sprang up a remarkable friendship between them. And one day on the occasion of a festival their master sacrificed the Cock and made a feast with his household. But the Purple Coot, deprived of its companion and unable to endure the loneliness, starved itself to death” (Aelian, On Animals 5.28).

A Cow mother’s intense love for her Calf was faithfully described by Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius (ca. 99-55 BCE):

“For often in front of the noble shrines of the gods a calf falls slain beside the incense-burning altars, breathing up a hot stream of blood from his breast; but the mother bereaved wanders through the green glens, and seeks on the ground the prints marked by the cloven hooves, as she surveys all the regions if she may espy somewhere her lost offspring, and coming to a stand fills the leafy woods with her moaning, and often revisits the stall, pierced with yearning for her calf; nor can tender willow-growths, and herbage growing rich in the dew, and those rivers flowing level with their banks, give delight to her mind and rebuff her sudden care, nor can the sight of other calves in the happy pastures divert her mind and lighten her load of care: so persistently she seeks for something of her own that she knows well” (Lucretius, De Rerum Natura 352-366).

On the Intelligence of Animals

Several ancient authors commented on the intelligence of various animal species.

For example, the intelligence of Cows and Baboons in Aelian’s On the Nature of Animals 7.1 and 6.10(i) and in Plutarch’s On the Intelligence of Animals 974d-e; the intelligence of the Mule in Plutarch (970a-b), Ants (967d-968b), Crows, Crocodiles, Elephants, Partridges, Deer, Fish such as Mullets, and Cranes, Tortoises, Dolphins, Horses.

Aelian on Baboons that dance and play instruments:

“Under the Ptolemies the Egyptians taught baboons their letters, how to dance, how to play the flute and the harp. And a baboon would demand money for these accomplishments, and would put what was given him into a bag which he carried attached to his person, just like professional beggars” (Aelian, On the Nature of Animals, 6.10[i]).

A figurine in the shape of a Baboon. Greece, ca. 6th-4th century BCE. UC Classics Library. On loan from the UC Art Collection. Could this figurine illustrate the passage in Aelian above about a baboon and its bag?

Plutarch on the intelligence of Ants:

“A matter obvious to everyone is the consideration ants show when they meet: those that bear no load always give way to those who have one and let them pass. Obvious also is the manner in which they gnaw through and dismember things that are difficult to carry or to convey past an obstacle, in order that they may make easy loads for several” (Plutarch, On the Intelligence of Animals 967f).

“But what goes beyond any other conception of their intelligence is their anticipation of the germination of wheat. You know, of course, that wheat does not remain permanently dry and stable, but expands and lactifies in the process of germination. In order, then, to keep it from running to seed and losing its value as food, and to keep it permanently edible, the ants eat out the germ from which springs the new shoot of wheat” (968a).

Animals do not need mnemonic devises

“Animals retain the memory of their experiences and have no need of those mnemonic systems devised by Simonides, by Hippias, and by Theodectes, or by any other of those who have been extolled for their profession and their skill in this matter. For instance, a cow goes to the spot where her calf was taken from her and mourns for it, lowing as is her wont” (Aelian, On the Nature of Animals 6.10[ii]).

Greco-Roman poet Oppian in treatises on fishing details the intelligence of Fish – Cuttle Fish, Prawn, Crab, Grey Mullet, Muraena, Bass, etc. (Oppian, Halieutica 2.120; 2.169; 3.92-188; 4.40-64).

Oppian (2nd century CE) on the intelligence of Fish:

“Fish employ cunning wit and deceitful craft and often deceive even the wise fishermen themselves and escape from the might of hooks and from the belly of the trawl when already caught in them and outrun the wits of men; outdoing them in craft, and become a grief to the fishermen” (Oppian, Halieutica 3.92-98).

Roman naturalist author Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) on the intelligence of Elephants:

“The elephant is the largest of them all, and in intelligence approaches the nearest to man. It understands the language of its country, it obeys commands, and it remembers all the duties which it has been taught. It is sensible alike of the pleasures of love and glory, and, to a degree that is rare among men even, possesses notions of honesty, prudence, and equity; it has a religious respect also for the stars, and a veneration for the sun and the moon” (Pliny, Natural History 8.1.).

Cruelty towards Animals in Antiquity

The use and exploitation of animals and Human cruelty and deception towards them are poignantly recounted in this ancient Egyptian allegory on a Demotic papyrus in Leiden:

“…One day it happened that he [a lion] met a panther whose fur was stripped, whose skin was torn, who was half dead and half alive [because of his] wounds. The lion said: How did you get into this condition? … The panther said: “It was man.” The lion said to him: Man, what is that?” The panther said: “There is no one more cunning than man. May you not fall into the hands of man!” The lion became enraged against man. He ran away from the panther in order to search for [man]. The lion encountered a team yoked […] […] so that one bit was in the mouth of the horse, the other bit [in the] mouth of the donkey. The lion said to them: “Who is he who has done this to you?” They said: “It is man, our master.” He said to them: “Is man mightier than you?” They said: …There is no one more cunning than man. May you not fall into the hand of man” The lion became enraged against man. He ran away from them.”

“The same happened to him with an ox and a cow, whose horns were clipped, whose noses were pierced, and whose heads were roped. He questioned them. They said the same. The same thing happened with a bear whose claws had been removed and whose teeth had been pulled. He asked them, saying: “Is man stronger than you?” He said: “That is the truth. I had a servant who prepared my food. He said to me: “Truly, your claws stick out from your flesh; you cannot pick up food with them. Your teeth protrude; they do not let food reach your mouth. Release me and I will cause you to pick up twice as much food!” When I released him, he removed my claws and my teeth. I have no food or strength without them! He strewed sand in my eyes and ran away from me. The lion became enraged against man. He ran away from the bear in order to search for man.”

“He met a lion who was [tied to] a tree of the desert, the trunk being closed over his paw and he was very distressed because he could not run away. The lion said to him: “How did you get into this evil condition? Who is he who did this to you?” The lion said to him: “It is man. Beware, do not trust him! Man is bad. Do not fall into the hand of man!” I had said to him: “What work do you do?” He said to me: “My work is giving old age. I can make for you an amulet, so that you will never die.” I went with him. He came to this tree of the mountain, sawed it, and said to me: “Stretch out your paw.” I put my paw between the trunk; he shut its mouth on it. When he had ascertained that my paw was fastened, so that I could not run after him, he strewed sand into my eyes and ran away from me. Then the lion laughed and said: “Man if you should fall into my hand, I shall give you the pain that you inflicted on my companion on the mountain!” (I 384).

Conclusion

In ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt many animals were sacred and well-treated. In Greece and Rome, too, animals could be sacred to gods and goddesses and pets, especially dogs, could receive their own burials with tombstones honoring them. And even though animals were eaten, plant protein was still the staple and there were no factory farms as today with more than 56 billion animals slaughtered each year and even though there were the occasional individual such as Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BCE) and, later in antiquity, physicians such as Greek Galen (129–ca. 210 CE) who performed dissections to study animal physiognomy, it cannot compare to the more than 100 million animals currently being killed throughout the world each year in today’s laboratories. And with a much smaller Human population, habitat loss was minimal compared to today and man-made climate change was not yet an issue. The greatest challenges non-Human animals faced in antiquity were animal sacrifice and the imperial Roman penchant for staging wild animal “fights” in the arena. As difficult as life for many animals was in antiquity, several of the ancient narratives and pleas on behalf of animals reveal a passion for animals and animal welfare, even animal rights sentiments, among some ancient individuals, echoed by contemporary animal rights advocates.

The Clifton Deer Project in Cincinnati is the successful initiative of University of Cincinnati Professor Christine Lottman to demonstrate that there are effective non-lethal methods to curb populations although since Deer has formed part of the Earth’s fauna for 3 million years without causing overpopulation, including in classical antiquity, the reason for the contemporary Deer “problem” might perhaps rather lie in the population explosion of the Human animal (7 billion and counting) and the Human-made deforestation and climate change of the last few decades? https://cliftondeer.org/

The famous “Il Porcellino,” a Baroque bronze fountain now in the Bardini museum in Florence, has become a symbol of the city (also making frequent appearances at Hogwarts in Harry Potter movies). The bronze sculpture harkens back to the ancestors of today’s Tuscans, the Etruscans and their Chimaera and She-Wolf. Hunting, especially of Wild Boar, as once among the Etruscans, is still a favorite pastime among some Tuscans. A couple of years ago, a law was passed to allow hunting in all corners of Tuscany, at all hours and all days of the year because the Boar, as the Fox in antiquity, is being blamed for destroying Tuscan vineyards. A majority of today’s Italians oppose hunting and there are organizations that actively fight against this law, using research and factual information to combat the erroneous perception of a “Wild Boar problem.” One of the smallest but most effective anti-hunting organizations in Florence is “Gabbie Vuote” (Empty Cages), named after a book by American philosopher Tom Regan. It uses as its motto a sentence in Latin from a controversial sermon (only a century after Descartes’ denial of any agency, intelligence, pain, or anxiety of animals) by English clergy and biographer James Granger (1723-1776): “Saevitia in bruta est tirocinium crudelitatis in homines” (savagery against animals is schooling for cruelty towards human beings). https://www.gabbievuote.it/caccia-al-cinghiale—relazione.html and https://www.gabbievuote.it/gli-animali-in-italia.htm

The Torre Argentina and the Cestius Pyramid Cat sanctuaries in present-day Rome to help abandoned Cats are situated at ancient Roman sites. Largo Argentina houses, besides the Cat sanctuary, four Roman Republic era temples (4th-2nd century BCE) and is the place where Julius Caesar was murdered in 44 BCE, at the Curia of the Theater of Pompeii. http://www.romancats.com/torreargentina/en/introduction.php

The Cestius Pyramid in Rome was a tomb built ca. 12 BCE. The caretakers of the Cestius pyramid Cats are archaeologists with the Superintendency of Roman antiquities. http://www.romancats.com/igattidellapiramide/index.php