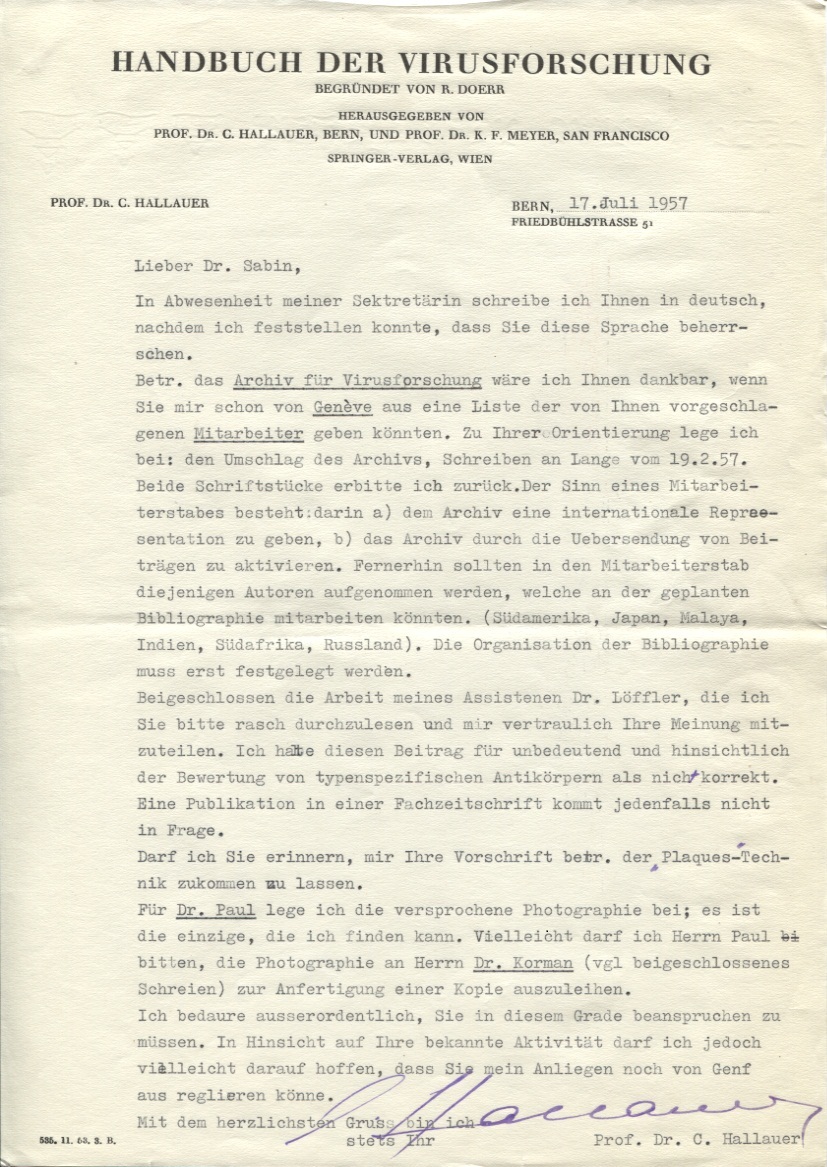

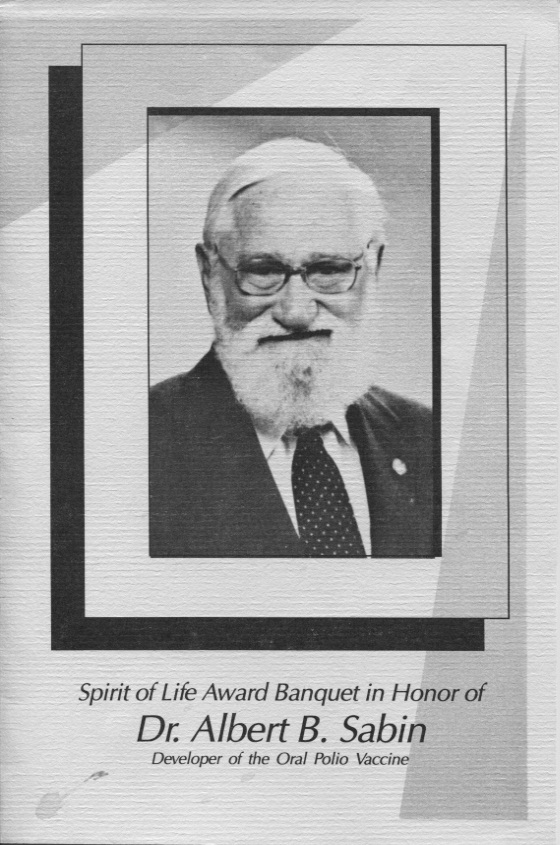

Being both a well-known scientist and a world traveler, Dr. Sabin’s collection of correspondence reflects many different parts of the world with letters in Russian, German, Portuguese, Spanish, Japanese, and more. As we move into the next phase of the Sabin digitization project, I will begin to look at the correspondence more closely, determining the important messages within each letter and assigning descriptive data (also known as metadata) to the letters so researchers can more easily search the material. In order to do this, I may need some help with those letters in foreign languages.

Here’s a recent example of a letter in a foreign language, as well as its background: