Staff Checking Motion Picture Film in Temporary Storage (National Archives and Records Administration)

For as long as archivists have been preserving the past, they have also considered what the future holds. The future has meant many things to archivists: the role of technology, the changing faces of our users, and the reasons for why we preserve records in the first place. As part of a book review I am writing, I recently delved into the writings of archivists who have reckoned with the future by doing a quick literature search across several major journals (American Archivist, Journal of the Society of Archivists/Archives and Records (UK and Ireland), Archives and Manuscripts (Australia) and Archivaria (Canada). This pulled up around 60 citations for articles with “future” in their titles, published in these four journals.

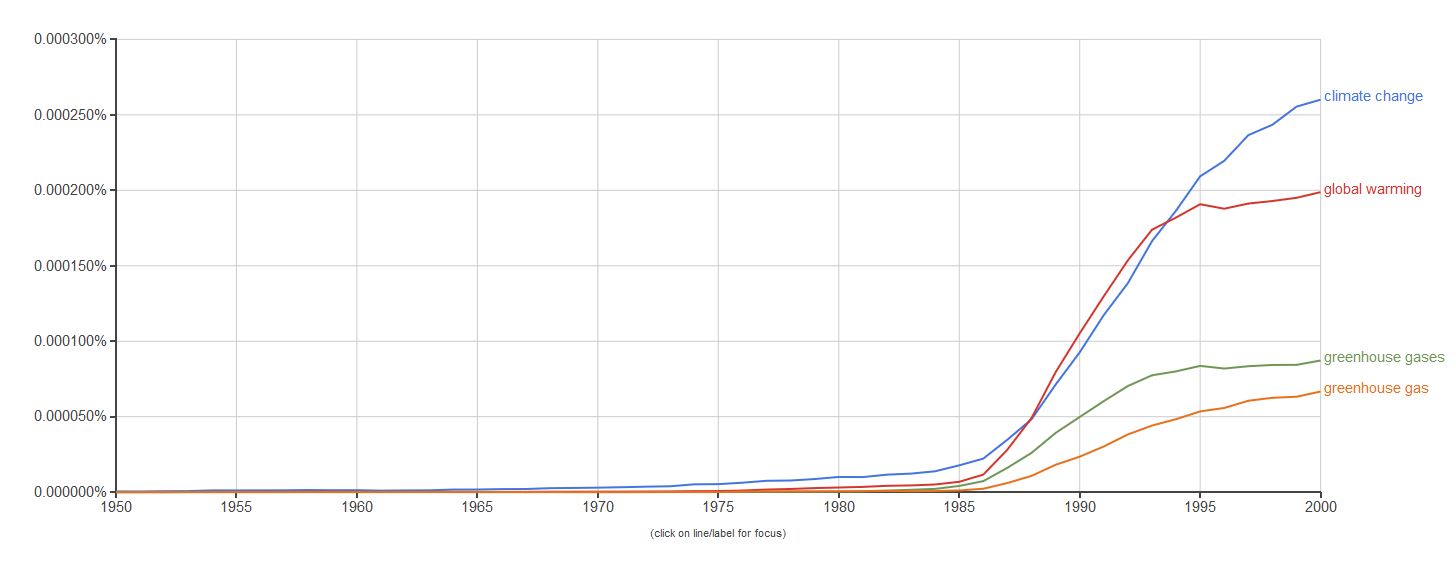

The four archival journals I pulled citations from started between the 1930s and 1970s. Although there are scattered “future” articles during the mid-twentieth-century, there were only five before 1974. Nearly half of all future-oriented articles were published since 2000. Clearly, the millennium triggered significant professional introspection on the direction of our profession.

The history of archival futurism in the last century has often concerned the role of rapidly-changing technology in the creation and preservation of records under archivists’ care. In fact, the very first article published in The American Archivist with the word “future” in its title (1939) concerned the preservation and reliability of motion picture technology.[1] Twenty years later (1958) brought “The Future of Microfilming,”[2] and two decades later (1977) we weren’t quite yet at cloud storage, but we were considering “Optical Memories: Archival Storage System of the Future, or More Pie in the Sky?”[3]

By the 80s, a note of anxiety began to creep into our archival futurism. Perhaps reflecting back cultural anxiety over the collapse of organized labor, rise of austerity measures, technological dystopias, and the late stages of the Cold War, archivists warned about “Instant Professionalism: To the Shiny New Men of the Future,”[4] and asked themselves “Is There a Future in the Use of Archives?”[5]

By the 2000s, the anxiety gave way to even more ominous warnings, many invoking worries of a digital dark age in which all of our bytes bite the dust. Archivists wrote about “Diaries, On-line Diaries, and the Future Loss to Archives; or, Blogs and the Blogging Bloggers Who Blog Them”[6] and “Saving-Over, Over-Saving, and the Future Mess of Writers’ Digital Archives: A Survey Report on the Personal Digital Archiving Practices of Emerging Writers.”[7] To give electronic records the materiality of their analog cousins, archivists used metaphors of manmade infrastructure (“Digital archives and metadata as critical infrastructure to keep community memory safe for the future – lessons from Japanese activities”[8]) and natural phenomena (“On the crest of a wave: transforming the archival future”[9]).

Archivists often summarize their work by saying “we preserve the past for the future.” This sentiment is visible in the titles, as nearly a quarter of the articles also contain a reference to the past, such as “What’s Past Was Future,”[10] “Seeing the Past as a Guidepost to Our Future,”[11] or “Metrics and Matrices: Surveying the Past to Create a Better Future.”[12] That anchoring of archival work in the work of the past, not just for its own sake today, but also for the benefits of users we may never meet, is perhaps what gives archivists such a unique sense of perspective among the GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums) sector.

There is no doubt that as long as archivists still exist, we’ll keep writing about the future. But sometimes looking at our own history of archival futurism tells us more about where our profession has been than when we’re headed next.

[1] Dorothy Arbaugh, “Motion Pictures and The Future Historian,” The American Archivist 2, no. 2 (April 1, 1939): 106–14, https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.2.2.7kv56p4206183040.

[2] Ernest Taubes, “The Future of Microfilming,” The American Archivist 21, no. 2 (April 1, 1958): 153–58, https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.21.2.26114m62333099k3.

[3] Sam Kula, “Optical Memories: Archival Storage System of the Future, or More Pie in the Sky?,” Archivaria 4 (1977): 43–48.

[4] George Bolotenko, “Instant Professionalism: To the Shiny New Men of the Future,” Archivaria 20 (1985): 149–157.

[5] David B. Gracy II, “Is There a Future in the Use of Archives?,” Archivaria 24 (1987): 3–9.

[6] Catherine O’Sullivan, “Diaries, On-Line Diaries, and the Future Loss to Archives; or, Blogs and the Blogging Bloggers Who Blog Them,” The American Archivist 68, no. 1 (January 1, 2005): 53–73, https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.68.1.7k7712167p6035vt.

[7] Devin Becker and Collier Nogues, “Saving-Over, Over-Saving, and the Future Mess of Writers’ Digital Archives: A Survey Report on the Personal Digital Archiving Practices of Emerging Writers,” The American Archivist 75, no. 2 (October 1, 2012): 482–513, https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.75.2.t024180533382067.

[8] Shigeo Sugimoto, “Digital Archives and Metadata as Critical Infrastructure to Keep Community Memory Safe for the Future – Lessons from Japanese Activities,” Archives and Manuscripts 42, no. 1 (January 2, 2014): 61–72, https://doi.org/10.1080/01576895.2014.893833.

[9] Laura Millar, “On the Crest of a Wave: Transforming the Archival Future,” Archives and Manuscripts 45, no. 2 (May 4, 2017): 59–76, https://doi.org/10.1080/01576895.2017.1328696.

[10] Maynard Brichford, “What’s Past Was Future,” The American Archivist 43, no. 3 (July 1, 1980): 431–32, https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.43.3.631227106ux2q512.

[11] Brenda Banks, “Seeing the Past as a Guidepost to Our Future,” The American Archivist 59, no. 4 (September 1, 1996): 392–99, https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.59.4.92486pp6w6p20575.

[12] Libby Coyner and Jonathan Pringle, “Metrics and Matrices: Surveying the Past to Create a Better Future,” The American Archivist 77, no. 2 (October 1, 2014): 459–88, https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.77.2.l870t2671m734116.

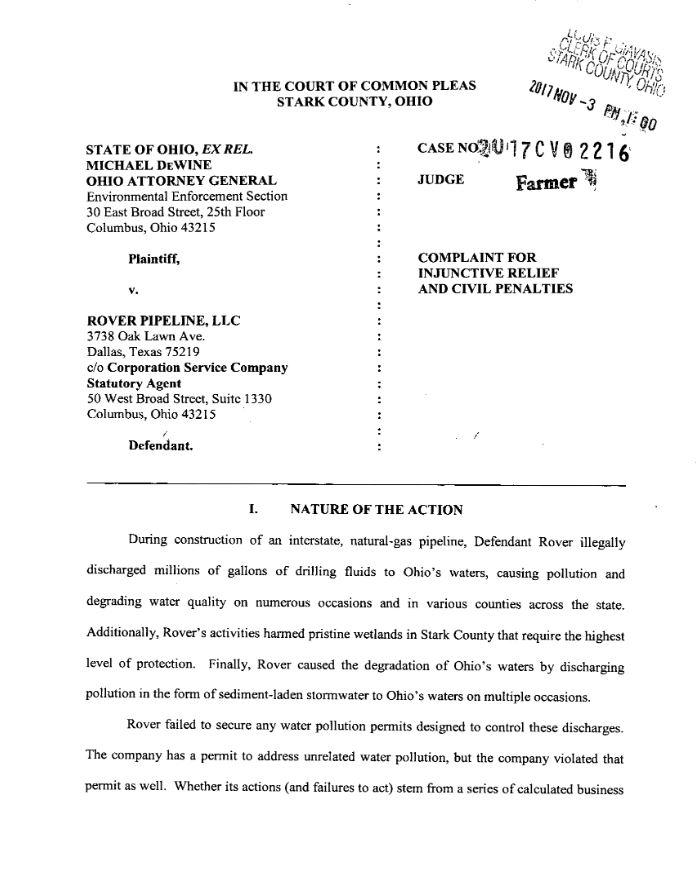

A foundational principle of archival theory and practice is that records have evidential value. Many users (and archivists themselves!) typically approach records for what informational value they have: What slogans are depicted in a photo of Vietnam-era student protesters waving signs? Can this birth certificate prove my great-grandmother’s birth date? Will this set of meeting minutes recall what decisions were made?

A foundational principle of archival theory and practice is that records have evidential value. Many users (and archivists themselves!) typically approach records for what informational value they have: What slogans are depicted in a photo of Vietnam-era student protesters waving signs? Can this birth certificate prove my great-grandmother’s birth date? Will this set of meeting minutes recall what decisions were made?