By Angela Vanderbilt

The story of abandoned subway stations and tracks hidden beneath busy city streets is not unique to Cincinnati. Other large cities, such as New York, London, and Paris have similarly mysterious and intriguing stories to tell. An article I recently read in The New York Times introduced me to this underground world of hidden subway ventilation shafts disguised by false building facades, with doors from which people occasionally exit, but never seem to enter. Some of these subterranean secrets are in use, while others have been abandoned like Cincinnati’s own subway stations beneath Central Parkway.

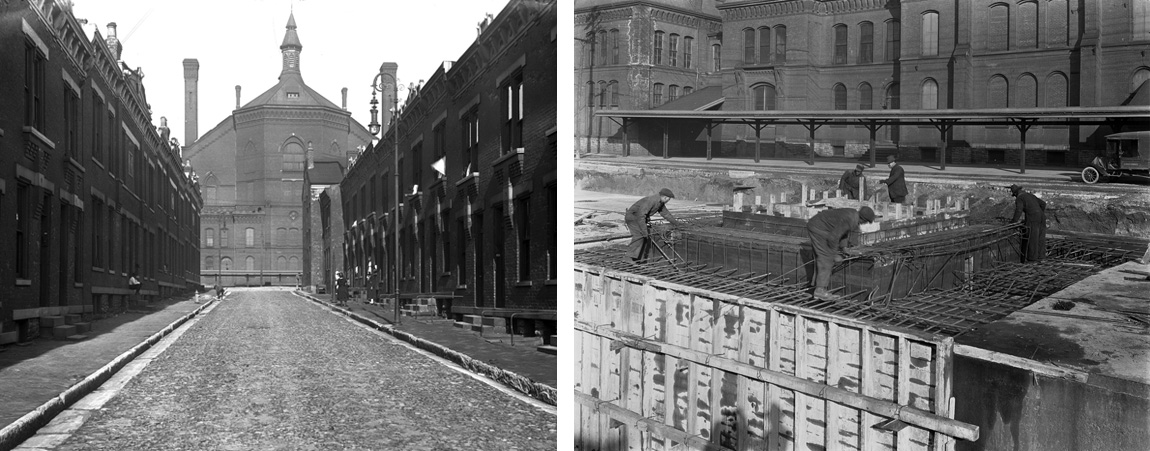

What’s fascinating is the effort made to disguise these facilities, to blend them in with the neighboring buildings. While it seems a logically aesthetic means of making the utilitarian more appealing, some have argued that the cities in which these structures are located are trying to hide a deep secret. For comparison, consider the Cincinnati subway – when the subway and Central Parkway were first being constructed, the ventilation chimneys and the entrances to the below-ground stations were nicely appointed with decorative stonework.

Ventilation shaft, looking north along Parkway from Liberty St., July 2, 1928

Close up of decorative stonework for ventilator railing, Central Parkway,

Nov. 19, 1928

Continue reading →

The University of Cincinnati Libraries have completed a three-year project to digitize the correspondence and photographs of Albert B. Sabin, developer of the oral polio vaccine and distinguished service professor at the University of Cincinnati’s College of Medicine and Children’s Hospital Research Foundation from 1939-1969.

The University of Cincinnati Libraries have completed a three-year project to digitize the correspondence and photographs of Albert B. Sabin, developer of the oral polio vaccine and distinguished service professor at the University of Cincinnati’s College of Medicine and Children’s Hospital Research Foundation from 1939-1969.