On a Tuesday May 29, 1453, a Turkish-Ottoman army of ca. 80,000 men, led by Sultan Mehmet II, captured the city of Constantinople after a 53-day siege, bringing to an end the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine empire. Rather than submit to the Sultan’s demand to surrender Constantinople, the emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos chose to die fighting in defense of the city and Christianity. Although the 7,000 defenders fought bravely, the city’s massive 5th c. CE walls, which had for a millennium proved impregnable to successive sieges, were no match for the Turkish cannons, and the 80,000-man Ottoman army overwhelmed the small defending force of Byzantines and their Italian allies. Once the emperor realized the city was lost, he threw off his imperial regalia and plunged into the midst of the fighting. His body was never found.

Constantinople had been an imperial capital since its founding by Roman Emperor Constantine the Great in 330. There have been numerous studies on the fall of Constantinople, but, according to Mike Braunlin, one of the most accessible to English readers is Sir Steven Runciman’s The Fall of Constantinople, 1453 (Cambridge 1965). The quoted sections that follow are from this book. On a Monday May 28th, realizing the end was near, the emperor encouraged his small force by reminding them what they were fighting for: “To his Greek subjects he said that a man should always be ready to die either for his faith or his country or for his family or for his sovereign. Now his people must be prepared to die for all four causes. He spoke of the glories and high traditions of the great Imperial city. He spoke of the perfidy of the infidel Sultan who had provoked the war in order to destroy the True Faith and to put his false prophet into the seat of Christ. He urged them to remember that they were the descendants of the ancient heroes of Greece and Rome and to be worthy of their ancestors. For his part, he said, he was ready to die for his faith, his city, and his people” (p. 130).

That evening the last Christian service was held in the great church of Holy Wisdom, the Hagia Sophia, which had been the heart of Eastern Orthodox Christianity for a thousand years. Roman Catholics and Greek Orthodox put aside their bitter doctrinal differences: “Priests who held union with Rome to be a mortal sin now came to the altar to serve their Unionist brothers. The Cardinal was there, and beside him bishops who would never acknowledge his authority; and all the people came to make confession and take communion, not caring whether Orthodox or Catholic administered it. There were Italians and Catalans along with the Greeks. The golden mosaics, studded with the images of Christ and his saints and the emperors and empresses of Byzantium, glimmered in the light of a thousand lamps and candles; and beneath them for the last time the priests in their splendid vestments moved in the solemn rhythm of the Liturgy. At this moment there was union in the Church of Constantinople” (p. 131).

Hagia Sophia, a Christian church in Constantinople until 1453, now an Islamic mosque in Istanbul.

As is often stated, there are at least two sides to every story (although some would argue that the Nazi occupation of much of Europe, or the U.S. invasion of Iraq, or the Russian invasion of Ukraine did not have two sides, but we leave that for another day). The atrocities committed by Christian crusaders against Muslims and Jews, including women and children, will not be covered in this blog post, but should be recognized as well. And whereas to Christians it was a Fall; to Muslims it was a Conquest.

For western Europe, the Fall of Constantinople had perhaps one silver-lining in that there was an ensuing migration of Byzantine scholars, scientists, musicians, astronomers, writers, poets, scribes, architects, artists, grammarians in the period following the Fall which brought with it a revival of Greek and Roman studies that eventually led to the development of Renaissance humanism and science.

Representing more than 1,000 years in a blog post is clearly impossible, so the following will instead offer a few highlights.

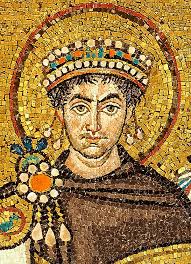

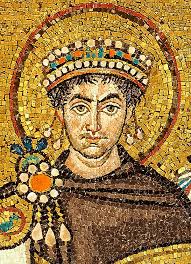

JUSTINIAN I

Emperor Justinian I, detail from mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy.

During the reign of Justinian I (reign 527–565), the Empire reached its greatest extent after reconquering much of the Roman western Mediterranean coast, including North Africa, Italy, and Rome itself, which it held for two more centuries. Justinian was considered by many the greatest of the Byzantine emperors. Two of his accomplishments include the uniform rewriting of Roman law, contained in the Corpus Iuris Civilis, which is still the basis of civil law in many countries, and the architectural masterpiece, the Hagia Sophia. The new law code gave the Church and Ruler the arguments to support the absolute right of the monarch with God’s approval, unbound by secular laws (legibus solutus) and answerable only to God. Justinian’s wife Theodora was highly influential in the politics of the Empire which perhaps speaks to the relative high status of women, at least among the Byzantine aristocracy.

THEODORA

Theodora and her court, mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy.

Theodora and her court, mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy.

The Nika revolt against Emperor Justinian during a week in 532 CE and Theodora’s pivotal council is famously narrated in Procopius’ History of the Wars (Ὑπὲρ τῶν πολέμων). I. 24. 32-38) and is here cited in toto.

“Οἱ δὲ ἀμφὶ τὸν βασιλέα ἐν βουλῇ ἦσαν, πότερα μένουσιν αὐτοῖς ἢ ταῖς ναυσὶν ἐς φυγὴν τρεπομένοις ἄμεινον ἔσται. καὶ λόγοι μὲν πολλοὶ ἐλέγοντο ἐς ἑκάτερα φέροντες. καὶ Θεοδώρα δὲ ἡ βασιλὶς ἔλεξε τοιάδε “Τὸ μὲν γυναῖκα ἐν ἀνδράσι μὴ χρῆναι τολμᾶν ἢ ἐν τοῖς ἀποκνοῦσι νεανιεύεσθαι, τὸν παρόντα οἶμαι καιρὸν ἥκιστα ἐφεῖναι διασκοπεῖσθαι εἴτε ταύτῃ εἴτε ἄλλῃ πη νομιστέον. οἷς γὰρ τὰ πράγματα ἐς κίνδυνον τὸν μέγιστον ἥκει, οὐκ ἄλλο οὐδὲν εἶναι δοκεῖ ἄριστον ἢ τὰ ἐν ποσὶν ὡς ἄριστα θέσθαι. ἡγοῦμαι δὲ τὴν φυγὴν ἔγωγε, εἴπερ ποτέ, καὶ νῦν, ἢν καὶ τὴν σωτηρίαν ἐπάγηται, ἀξύμφορον εἶναι. ἀνθρώπῳ μὲν γὰρ ἐς φῶς ἥκοντι τὸ μὴ οὐχὶ καὶ νεκρῷ γενέσθαι ἀδύνατον, τῷ δὲ βεβασιλευκότι 36τὸ φυγάδι εἶναι οὐκ ἀνεκτόν. μὴ γὰρ ἂν γενοίμην τῆς ἁλουργίδος ταύτης χωρίς, μηδ᾿ ἂν τὴν ἡμέραν ἐκείνην βιῴην, ἐν ᾗ με δέσποιναν οἱ ἐντυχόντες οὐ προσεροῦσιν. εἰ μὲν οὖν σώζεσθαί σοι βουλομένῳ ἐστίν, ὦ βασιλεῦ, οὐδὲν τοῦτο πρᾶγμα. χρήματα γάρ τε πολλὰ ἔστιν ἡμῖν, καὶ θάλασσα μὲν ἐκείνη, πλοῖα δὲ ταῦτα. σκόπει μέντοι μὴ διασωθέντι ξυμβήσεταί σοι ἥδιστα ἂν τῆς σωτηρίας τὸν θάνατον ἀνταλλάξασθαι. ἐμὲ γάρ τις καὶ παλαιὸς ἀρέσκει λόγος, ὡς καλὸν ἐντάφιον 38ἡ βασιλεία ἐστί.” τοσαῦτα τῆς βασιλίδος εἰπούσης, θάρσος τε τοῖς πᾶσιν ἐπεγένετο καὶ ἐς ἀλκὴν τραπόμενοι ἐν βουλῇ ἐποιοῦντο ᾗ ἂν ἀμύνεσθαι δυνατοὶ γένοιντο, ἤν τις ἐπ᾿ αὐτοὺς πολεμήσων ἴοι.”

“Now the emperor and his court were deliberating as to whether it would be better for them if they remained or if they took to flight in the ships. And many opinions were expressed favoring either course. And the Empress Theodora also spoke to the following effect: ‘As to the belief that a woman ought not to be daring among men or to assert herself boldly among those who are holding back from fear, I consider that the present crisis most certainly does not permit us to discuss whether the matter should be regarded in this or in some other way. For in the case of those whose interests have come into the greatest danger nothing else seems best except to settle the issue immediately before them in the best possible way. My opinion then is that the present time, above all others, is inopportune for flight, even though it bring safety. For while it is impossible for a man who has seen the light not also to die, for one who has been an emperor it is unendurable to be a fugitive. May I never be separated from this purple, and may I not live that day on which those who meet me shall not address me as mistress. If, now, it is your wish to save yourself, O Emperor, there is no difficulty. For we have much money, and there is the sea, here the boats. However consider whether it will not come about after you have been saved that you would gladly exchange that safety for death. For as for myself, I approve a certain ancient saying that royalty is a good burial-shroud.’ When the queen had spoken thus, all were filled with boldness, and, turning their thoughts towards resistance, they began to consider how they might be able to defend themselves if any hostile force should come against them.”

HYPATIA

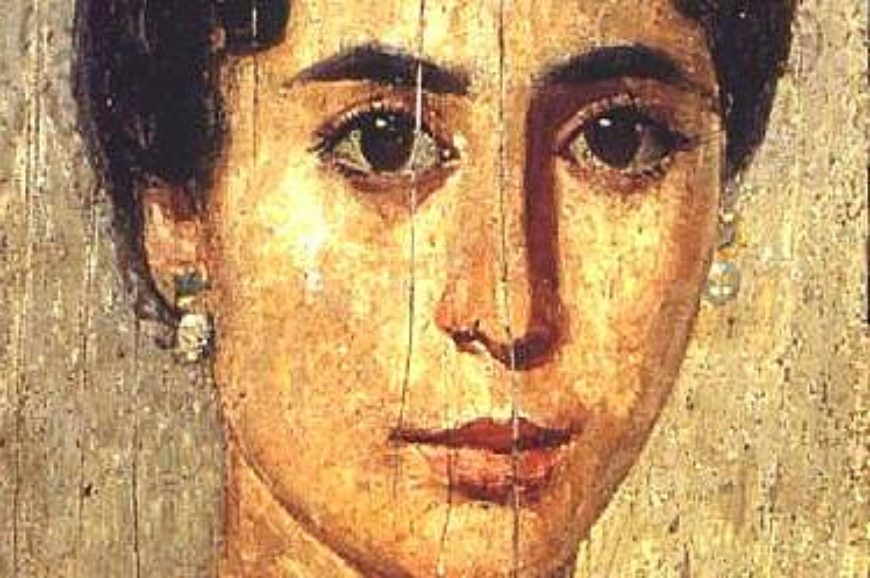

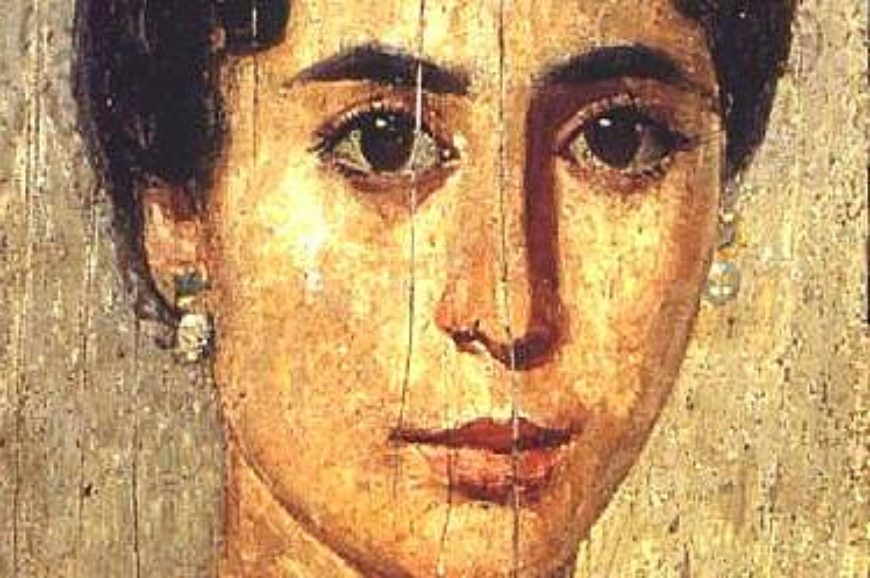

The relative freedom of women in Byzantium may also be manifest in the figure of Neoplatonist philosopher, astronomer, and mathematician Hypatia (born ca. 350–370; died 415 CE) who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, where she was the Head of the renowned Neoplatonic school in Alexandria until she was murdered in March 415 CE by a mob of Christian monks known as the parabalani. Ostensibly, the reason was political as one side accused her of siding with Orestes, the Roman prefect of Alexandria, who was feuding with Cyril, the bishop of Alexandria. However, the fact that she was an intelligent and influential woman and pagan no doubt played a significant role in her murder.

Gilded Mummy Portrait of a Woman, often referred to as Hypatia. From Εr-Rubayat, Egypt. Roman Period, about C.E. 160–170.

Fifth century church historian Socrates Scholasticus of Constantinople praised her (text available in Patrologia Graeca vol. 67 through Google Books http://patristica.net/graeca/).

“Ἦν τις γυνὴ ἐν τῇ Ἀλεξανδρείᾳ τοὔνομα Ὑπατία. Αὕτη

Θέωνος μὲν τοῦ φιλοσόφου θυγάτηρ ἦν, ἐπὶ τοσοῦτο δὲ

προὔβη παιδείας, ὡς ὑπερακοντίσαι τοὺς κατ’ αὐτὴν φιλοσό-

φους, τὴν δὲ Πλατωνικὴν ἀπὸ Πλωτίνου καταγομένην δια

τριβὴν διαδέξασθαι καὶ πάντα τὰ φιλόσοφα μαθήματα τοῖς

βουλομένοις ἐκτίθεσθαι. Διὸ καὶ οἱ πανταχόθεν φιλοσοφεῖν

βουλόμενοι συνέτρεχον παρ’ αὐτήν. Διὰ δὲ τὴν προσοῦ-

σαν αὐτῇ ἐκ τῆς παιδεύσεως σεμνὴν παρρησίαν καὶ τοῖς

ἄρχουσιν σωφρόνως εἰς πρόσωπον ἤρχετο, καὶ οὐκ ἦν τις

αἰσχύνη ἐν μέσῳ ἀνδρῶν παρεῖναι αὐτήν· πάντες γὰρ δι’

ὑπερβάλλουσαν σωφροσύνην πλέον αὐτὴν ᾐδοῦντο καὶ κατε-

πλήττοντο” (Socrates Scholastics. Historia Ecclesiastica 7.15).

“There was a woman at Alexandria named Hypatia, daughter of the philosopher Theon, who made such attainments in literature and science, as to far surpass all the philosophers of her own time. Having succeeded to the school of Plato and Plotinus, she explained the principles of philosophy to her auditors, many of whom came from a distance to receive her instructions. On account of the self-possession and ease of manner, which she had acquired in consequence of the cultivation of her mind, she not infrequently appeared in public in presence of the magistrates. Neither did she feel abashed in coming to an assembly of men. For all men on account of her extraordinary dignity and virtue admired her the more.”

The historian Hesychius from Alexandria referred to her as the greatest astronomer (the best in matters of astronomy) “μάλιστα εἰς τὰ περὶ ἀστρονομίας” (frag. 7. 1002).

The Egyptian Coptic bishop John of Nikiû (fl. 680-690) seemed less “impressed”:

“And in those days there appeared in Alexandria a female philosopher, a pagan named Hypatia, and she was devoted at all times to magic, astrolabes and instruments of music, and she beguiled many people through her Satanic wiles. And the governor of the city honored her exceedingly; for she had beguiled him through her magic. And he ceased attending church as had been his custom… And he not only did this, but he drew many believers to her, and he himself received the unbelievers at his house” (John of Nikiû’s Chronicle 1916, 84:87-88, Translation from the Ethiopic version, Text and Translation Society: https://archive.org/stream/JohnOfNikiuChronicle1916/John_of_Nikiu_Chronicle_1916_djvu.txt).

Socrates Scholasticus recounts her murder:

“ἐκ τοῦ δίφρου ἐκβαλόντες ἐπὶ τὴν ἐκκλησίαν,

ᾗ ἐπώνυμον Καισάριον, συνέλκουσιν,

ἀποδύσαντές τε τὴν ἐσθῆτα ὀστράκοις ἀνεῖλον, καὶ

μεληδὸν διασπάσαντες ἐπὶ τὸν καλούμενον Κιναρῶνα

τὰ μέλη συνάραντες πυρὶ κατανήλωσαν”

(Socrates Scholasticus. Historia Ecclesiastica, book 7 chapter 15).

“They dragged her into a nearby church, known as the Caesarion, where they stripped her naked and murdered her using ostraka. They tore her body into pieces and dragged her mangled limbs through the town to a place called Cinarion, where they set them on fire.”

MYSTRAS

The Byzantine town Mystras or Mistras (Greek Μυστρᾶς/Μιστρᾶς) was the capital of the Byzantine Despotate of Morea during the 14th and 15th centuries. The remains of its many splendid churches are located on Mt. Taygetos near ancient Sparta. While an undergraduate, visiting Mystras on top of Taygetos during a spectacular thunder and lightning storm added a mystical feeling to its now rather ghost-like but still impressive appearance. The Peribleptos Monastery houses some remarkable frescoes from the mid to late 14th century (seen in the image below). Interestingly, devotion to Virgin Mary appears to have been an iconic focus at Mystras. Mystras can also lay claim to being the last bastion of Byzantine scholarship; the Neoplatonist philosopher Georgius Gemistos (Plethon) lived there until his death in 1452. He reintroduced Plato’s ideas to Western Europe during the 1438–1439 Council of Florence and in the process is thought to have heralded the Italian humanist renaissance. He is believed to have influenced Cosimo de’ Medici to found the new Academy (Accademia Platonica), at which Marsilio Ficino translated all of Plato’s works into Latin.

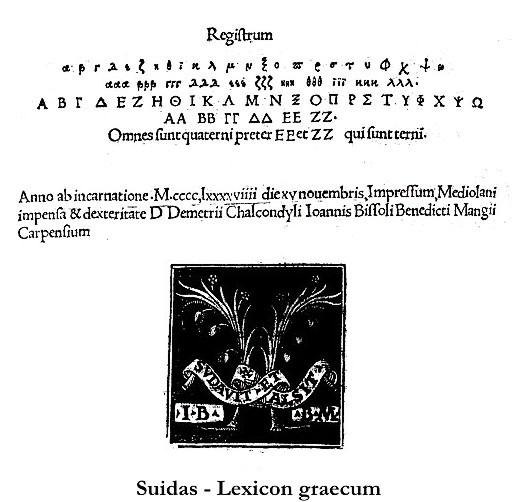

THE SUDA

The Suda or Souda (Byzantine Greek Σοῦδα “fortress”, Latin Suidae Lexicon) with the alternate name Suidas stemming from an error made by Greek scholar Eustathius who mistook the title for the author’s name, is an extensive 10th-century lexical encyclopaedia of c. 30,000 entries concerning the Mediterranean world (http://www.stoa.org/sol/). Many of the entries draw on ancient sources that have since been lost and derived from medieval Christian compilers. It is an invaluable source for ancient and Byzantine lexicography, history and life, although the reliability of some of its ancient entries has been called into question such as the biographical information about an alleged husband and daughter of the ancient Greek poet Sappho. If we are to trust the Suda (s.v. Σαπφώ),

ἐγαμήθη δὲ ἀνδρὶ Κερκύλᾳ πλουσιωτάτῳ, ὁρμωμένῳ ἀπὸ Ἄνδρου, καὶ θυγατέρα ἐποιήσατο ἐξ αὐτοῦ, ἣ Κλεὶς ὠνομάσθη.

her husband’s name was “Kerkylas from the Isle of Andros” which would be the equivalent of “Penis from the Isle of Man,” a reference which most likely stems from the many comedies about Sappho, popular already in antiquity, and the reference to a “daughter” Kleϊs (Sappho 98bV) may simply refer to a young woman, more or less the equivalent of lovers calling each other “baby.” In the fragmentary Sapphic corpus the word pais (παίς), “child” means girl or child 10 times and “somebody’s child” 5 times.

For Byzantine things more contemporary with the Suda the level of reliable information increases. It is an important source for classical antiquity as well, especially for lexical information, but, as we saw, with some caveats.

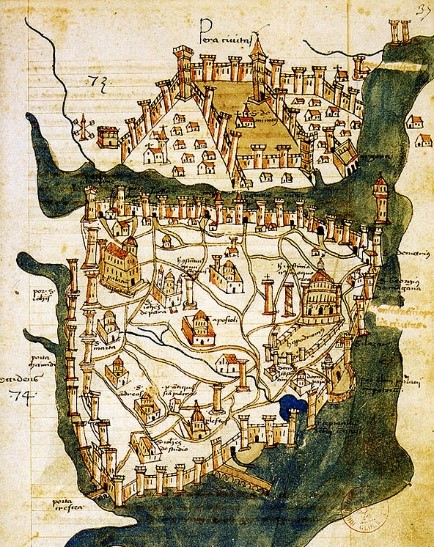

CARTOGRAPHY AND ARCHAEOLOGY

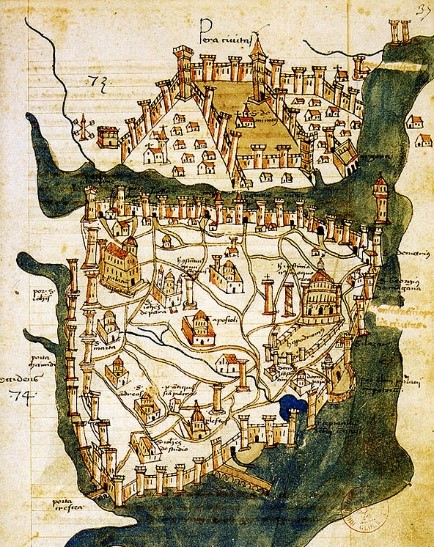

Map of Constantinople (1422) by Buondelmonti, contained in Liber insularum Archipelagi (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris) is the oldest surviving map of the city, and the only one which antedates the Turkish conquest of the city in 1453.

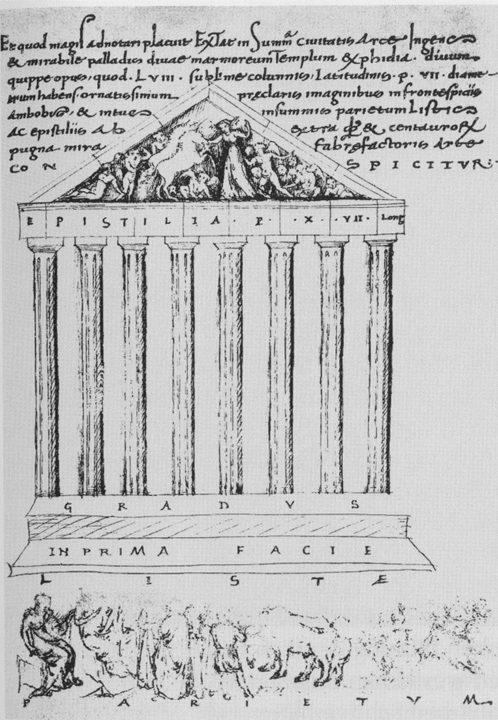

At the turn of the 14th century two Italians, Cristoforo Buondelmonti and Cyriacus de’ Pizzicolli, broke with the tradition of spending their days scrutinizing texts of ancient authors or searching for manuscripts, and instead sought to record the material culture of classical antiquity. To Buondelmonti, a Florentine monk, we owe the first attempt at cartography applied to Greece, and to Cyriacus, a merchant from Ancona, the beginnings of modern day archaeology. In fact, he considered the monuments and inscriptions to be more faithful witnesses of classical antiquity than the texts of ancient writers.

“At et cum maximas per urbem tam generosissimae gentis reliquias undique solo disiectas aspexisset, lapides et ipsi magnarum rerum gestarum maiorem longe quam ipsi libri fidem et notitiam spectantibus praebere videbantur” (Francesco Scalamonti, Vita Kyriaci Anconitani 56).

“It appeared to him, as he looked upon the great remains left behind by so noble a people, cast to the ground throughout the city, that the stones themselves afforded to modern spectators much more trustworthy information about their splendid history than what was to be found in books.”

In Constantinople in 1444 he was involved in the preparation of the crusade against the Turks in large measure to preserve the material remains of ancient Greece. The historian and humanist scholar Poggio Bracciolini, the author of “the most famous jokebook of the Renaissance” (Bowen, 1988, p. 5), notes sarcastically:

“Ciriacus Anconitanus, homo verbosus et nimium loquax, deplorabat aliquando, astantibus nobis, casum atque eversionem Imperii Romani, inque ea re vehementius angi videbatur” (Facetiae or Jocose Tales of Poggio, vol. I, ch. 82).

“Cyriacus of Ancona, a verbose and inexhaustible speaker, sometimes deplored the fall and breakup of the Roman Empire before our eyes; it seemed to cause him terrible anguish.”

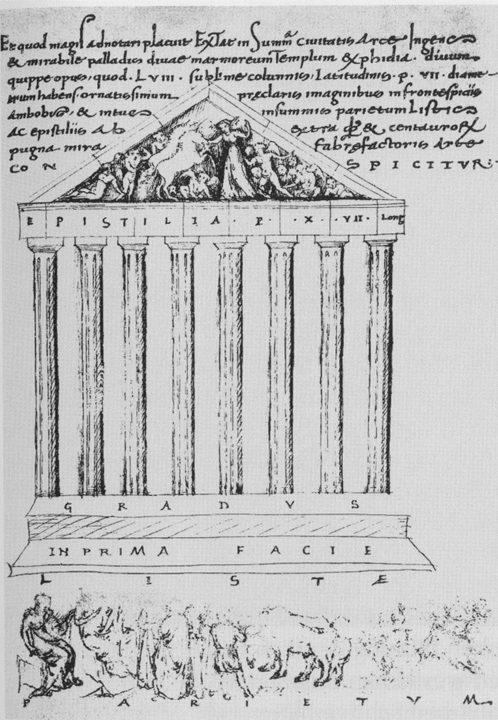

Cyriacus’ drawing of the Parthenon from 1444 with its frieze and pediments intact.

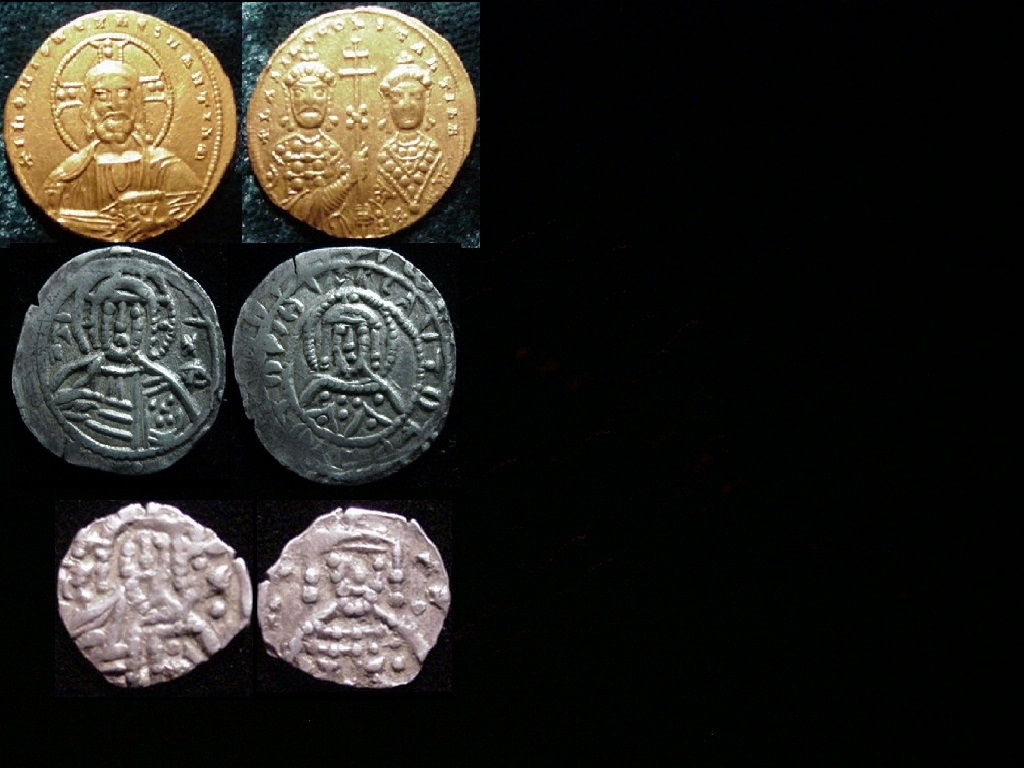

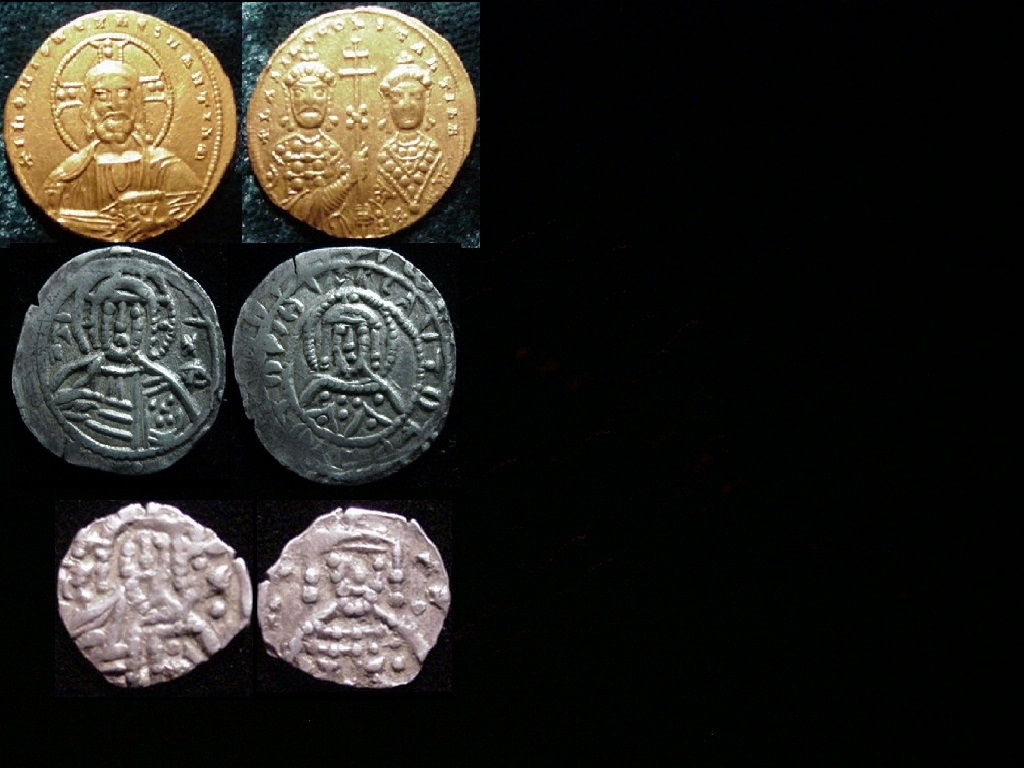

COINS

Having a resident Byzantine coin expert we would be remiss if we did not also include the following perfect illustration of the Zenith and Fall of Byzantium.

The first photo represents a copper follis of Justinian I, perhaps the last Byzantine emperor whose native language was Latin. He sought to restore to the empire the western provinces, which had been lost in the 5th century. On the obverse, the emperor is depicted as a Roman “Imperator,” in military dress and helmet, and he holds in his right hand a globe representing the world, surmounted by a cross. The reverse displays pertinent details about the coin and its manufacture; it is a denomination valued at 40 nummia (the large mu = 40), struck at CON(stantinople), bearing the date ANNO XIII = 539/40. The epsilon beneath the mark of value M tells us the coin was struck in the 5th workshop of the Constantinople mint (gratias Mike).

The second photo shows the development of Christian religious iconography on the coinage, in this case, the type of Christ/portrait of emperor and its increasing poverty of representation echoing the decline of the empire. The obverse portrait of Christ, shown nimbate, with the cross represented behind him, is adapted from icons. Christ holds in his left hand a book of the Gospels (on the viewer’s right), the cover of which is decorated with jewels (most visible on the middle coin — there are 5 jewels there). Christ’s right hand (on the viewer’s left) is raised in a gesture derived from Roman artistic convention representing speech. The top coin is a gold nomisma of Basil II, 976-1025, whom later Byzantine writers nicknamed Boulgaroktonos, the “Bulgar‐Slayer,” because he blinded an army of 15,000 captives and thereby not only destroyed the army but also broke the spirit of the Bulgarian state which ultimately led to it being subsumed under the Byzantine empire. Basil appears on the left, accompanied by his brother Constantine VIII, who enjoyed nominal imperial power while his brother ran the empire. Basil’s reign ushered in the zenith of Byzantine power and influence in the middle ages. The next coin, in silver, was struck under the emperor John V Palaiologos, 1341-91, and one can see the growing stylization of the types, which is brought to an even more extreme state in the last coin, again, in silver, of Constantine XI, 1448-1453.

Christ Pantocrator mosaic in the Cathedral of Monreale, Sicily (constructed between 1170 and 1189).

Brief bibliography

On the Fall:

Barbaro, Nicolò. Diary of the Siege of Constantinople, 1453. Translated [from the Italian] by J. R. Jones. New York, Exposition Press [1969]. cl-g DF649 .B313

Carroll, Margaret G. A Contemporary Greek Source for the Siege of Constantinople, 1453: The Sphrantzes Chronicle. Amsterdam: A.M. Hakkert, 1985. cl-g DF645.P483 C37 1985

Haldon, John F. The Fall of Constantinople: The Ottoman Conquest of Byzantium. Oxford; New York : Osprey, 2007. cl-g DR730 .H35 2007

Phrantzes, Georgius. Chronikon Geōrgiou Phrantzē. English. The Fall of the Byzantine Empire: A Chronicle; translated by Marios Philippides. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1980. cl-g DF645 .G4813

Runciman, Steven, Sir. The Fall of Constantinople, 1453. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965. cl-g DF649 .R8

On Byzantium in general:

Garland, Lynda. Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527-1204. London; New York: Routledge, 1999. cl-g DF572.8.E5 G37 1999

Gregory, Timothy E. A History of Byzantium. 2nd ed. Chichester, U.K.; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. cl-g DF552 .G68 2010

Haldon, John F. Byzantium: A History. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus; Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2000. cl-g DF521 .H32 2000

Herrin, Judith. Women in Purple: Rulers of Medieval Byzantium. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2001. cl-g DF581.3 .H47 2001

__________. Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007. cl-g DF521 .H477 2007

Mango, Cyril, ed. The Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. cl-g DF552 .O94 2002

Shepard, Jonathan, ed. The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire c. 500-1492. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008. cl-g DF571 .C34 2008

Treadgold, Warren. A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997. cl-g DF552 .T65 1997

UC Libraries will be closed Monday, Nov. 11 in observance of Veterans Day, except for the Donald C. Harrison Health Sciences Library, which will be open 9am to 5pm.

UC Libraries will be closed Monday, Nov. 11 in observance of Veterans Day, except for the Donald C. Harrison Health Sciences Library, which will be open 9am to 5pm.

UC Libraries will be closed Monday, September 2 for Labor Day, except for the

UC Libraries will be closed Monday, September 2 for Labor Day, except for the

Theodora and her court, mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy.

Theodora and her court, mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy.