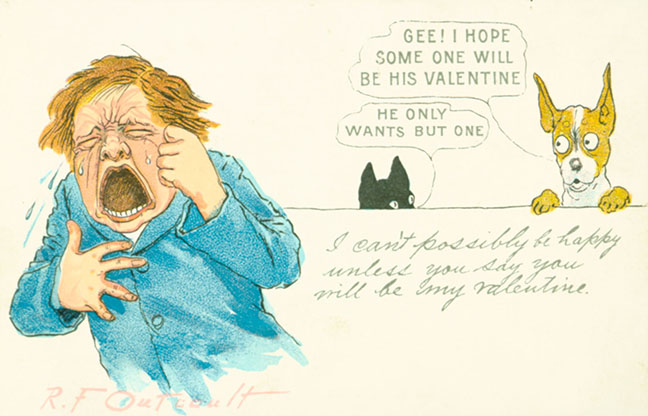

Something to read and ponder on this most lovable day

The love of a man as passionately expressed by Roman poet Catullus (and to the delight of all school children studying Latin)

https://www.loebclassics.com/view/catullus-poems/1913/pb_LCL006.7.xml?result=1&rskey=Fz5uL7

“…da mi basia mille, deinde centum, dein mille altera, dein secunda centum, deinde usque altera mille, deinde centum dein, cum milia multa fecerimus, conturbabimus illa, ne sciamus, aut nequis malus invidere possit, cum tantum sciat esse basiorum…” (5)

“…give me a thousand kisses, then a hundred, then another thousand, then a second hundred, then yet another thousand, then a hundred. Then, when we have made up many thousands, we will confuse our counting, that we may not know the reckoning, nor any malicious person blight them with evil eye, when he knows that our kisses are so many…”

The love of a woman as expressed by the greatest of the Ancient Greek lyric poets, Sappho

https://www.loebclassics.com/view/sappho-fragments/1982/pb_LCL142.79.xml?mainRsKey=v1YYtJ&result=2&rskey=i9iJXE

“…ὠς γὰρ ἔς σ᾿ἴδω βρόχε᾿, ὤς με φώναισ᾿ οὐδ᾿ ἒν ἔτ᾿εἴκει, ἀλλὰ κὰμ μὲν γλῶσσᾴ <μ> ἔαγε, λέπτονδ᾿ αὔτικα χρῷ πῦρ ὐπαδεδρόμηκεν, ὀππάτεσσι δ᾿οὐδ᾿ ἒν ὄρημμ᾿, ἐπιρρόμβεισι δ᾿ἄκουαι, κὰδ δέ μ᾿ἴδρως κακχέεται, τρόμος δὲπαῖσαν ἄγρει, χλωροτέρα δὲποίας ἔμμι…” (frag. 31.7-14).

“…for when I look at you for a moment, then it is no longer possible for me to speak; my tongue has snapped, at once a subtle fire has stolen beneath my flesh, I see nothing with my eyes, my ears hum, sweat pours from me, a trembling seizes me all over, I am greener than grass…”

The touching love of a dog in Homer’s Odyssey

https://www.loebclassics.com/view/homer-odyssey/1919/pb_LCL105.175.xml?mainRsKey=TOKAcJ&result=1&rskey=vLoZ2S

“…ἂν δὲ κύων κεφαλήν τε καὶ οὔατα κείμενος ἔσχεν, Ἄργος, Ὀδυσσῆος ταλασίφρονος… ἔνθα κύων κεῖτ᾿ Ἄργος, ἐνίπλειος κυνοραιστέων. δὴ τότε γ᾿, ὡς ἐνόησεν Ὀδυσσέα ἐγγὺς ἐόντα οὐρῇ μέν ῥ᾿ ὅ γ᾿ἔσηνε καὶ οὔατα κάββαλεν ἄμφω, ἆσσον δ᾿οὐκέτ᾿ ἔπειτα δυνήσατο οἷο ἄνακτοςἐλθέμεν…” (17. 290-291; 302-304).

“…and a dog that lay there raised his head and pricked up his ears, Argus, steadfast Odysseus’ dog… There lay the dog Argus, full of dog ticks. But now, when he became aware that Odysseus was near, he wagged his tail and dropped both ears, but nearer to his master he had no longer strength to move…”

The love of a cow for her newborn calf when he is brutally taken away to be sacrificed in Lucretius

https://www.loebclassics.com/view/lucretius-de_rerum_natura/1924/pb_LCL181.123.xml?rskey=phideb&result=1

“…nam saepe ante deum vitulus delubra decora turicremas propter mactatus concidit aras, sanguinis expirans calidum de pectore flumen; at mater viridis saltus orbata peragrans quaerit humi pedibus vestigia pressa bisulcis, omnia convisens oculis loca si queat usquam conspicere amissum fetum, completque querellis frondiferum nemus adsistens et crebra revisit ad stabulum desiderio perfixa iuvenci; nec tenerae salices atque herbae rore vigentes fluminaque illa queunt summis labentia ripis oblectare animum subitamque avertere curam, nec vitulorum aliae species per pabula laeta derivare queunt animum curaque levare: usque adeo quiddam proprium notumque requirit…” (2.352-366).

“…for often in front of the noble shrines of the gods a calf falls slain beside the incense-burning altars, breathing up a hot stream of blood from his chest; but the mother, bereaved, wanders through the green glens, and knows the prints marked on the ground by the cloven hooves, as she surveys all the regions if she may espy somewhere her lost offspring, and coming to a stand fills the leafy woods with her moaning, and often revisits the stall pierced with yearning for her young calf; nor can tender willow-growths, and grass growing rich in the dew, and those rivers flowing level with their banks, give delight to her mind and rebuff that care which has entered there, nor can the sight of other calves in the happy pastures divert her mind and lighten her load of care: so persistently she seeks for something of her own that she knows well…”

The love of nature longingly expressed by Vergil in Eclogue 1

https://www.loebclassics.com/view/virgil-eclogues/1916/pb_LCL063.29.xml?mainRsKey=z6gF20&result=2&rskey=9aEESD

“…fortunate senex, hic inter flumina notaet fontis sacros frigus captabis opacum. hinc tibi, quae semper, vicino ab limite saepes Hyblaeis apibus florem depasta salicti saepe levi somnum suadebit inire susurro; hinc alta sub rupe canet frondator ad auras: nec tamen interea raucae, tua cura, palumbes, nec gemere aëria cessabit turtur ab ulmo” (Ecl. 1.51-58).

“…happy old man! Here, amid familiar streams and sacred springs, you shall enjoy the cooling shade. On this side, as of old, on your neighbor’s border, the hedge whose willow blossoms are sipped by Hybla’s bees shall often with its gentle hum soothe you to slumber; on that, under the towering rock, the woodman’s song shall fill the air; while still the cooing wood pigeons, your pets, and the turtle dove shall cease not their moaning from the elm tops.”

One of the many rather twisted love stories in Ovid’s Metamorphoses — Pyramus and Thisbe, Apollo and Daphne, Orpheus and Eurydice and countless others

https://www.loebclassics.com/view/ovid-metamorphoses/1916/pb_LCL042.3.xml?rskey=XVZ0kK&result=3

That of Cupid (Eros) himself (and Psyche) in Apuleius

https://www.loebclassics.com/view/apuleius-metamorphoses/1989/pb_LCL044.259.xml?result=2&rskey=4iNfhs

Happy Reading!

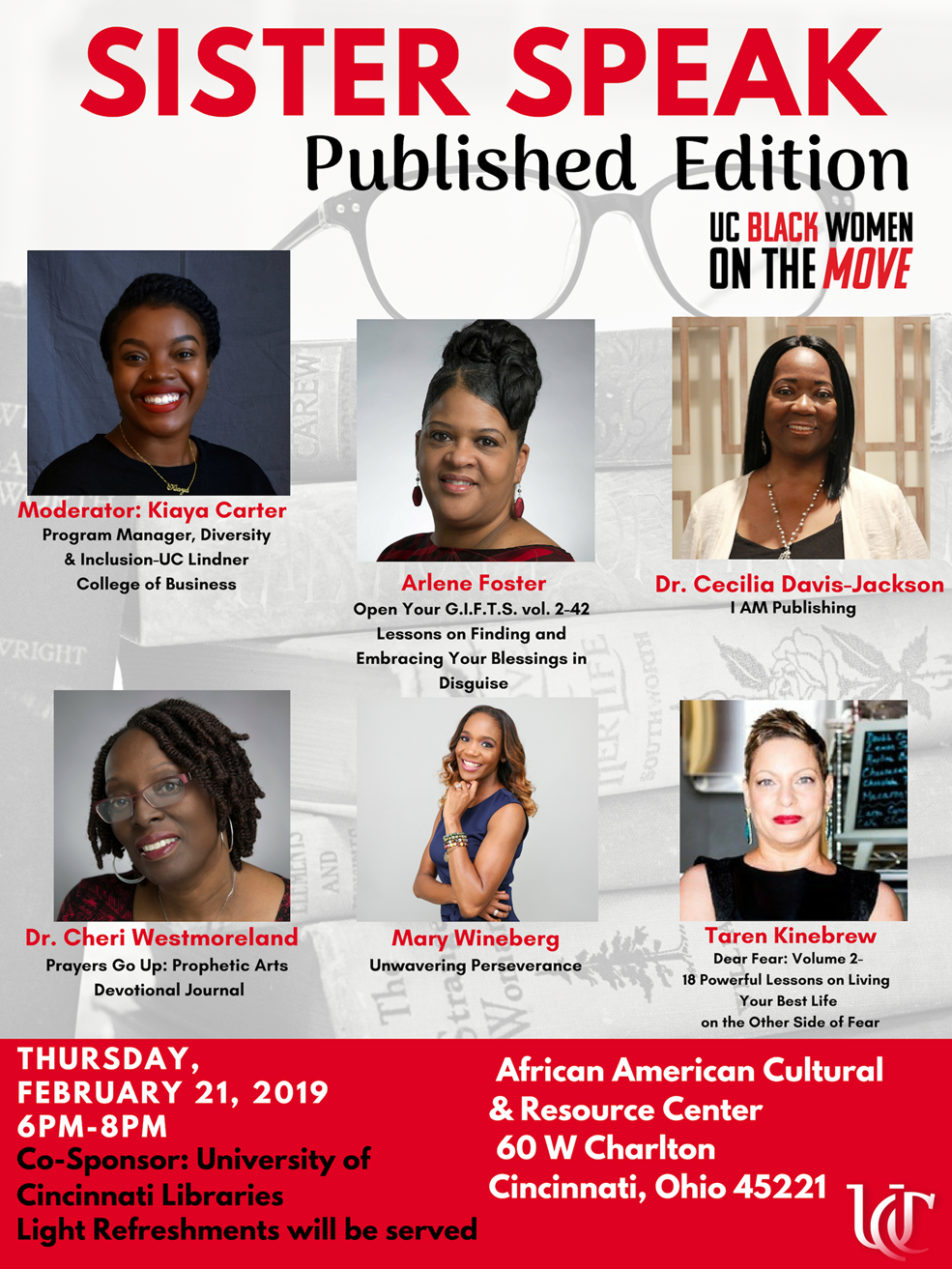

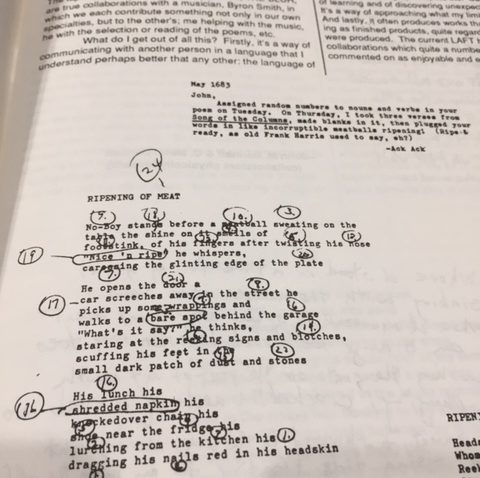

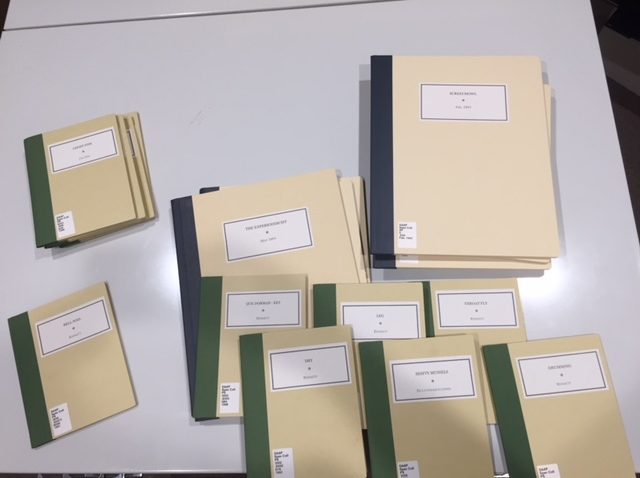

Life of the Mind, interdisciplinary conversations with UC faculty, will return Wednesday, March 6, 2019 from 2:30-4:30pm, in TUC 400B with a lecture by Stephen Meyer, professor of musicology in the College-Conservatory of Music. Professor Meyer will speak on “Beyond Decanonization: The Future of Humanities in the Neoliberal University.”

Life of the Mind, interdisciplinary conversations with UC faculty, will return Wednesday, March 6, 2019 from 2:30-4:30pm, in TUC 400B with a lecture by Stephen Meyer, professor of musicology in the College-Conservatory of Music. Professor Meyer will speak on “Beyond Decanonization: The Future of Humanities in the Neoliberal University.”