Larissa Bonfante, Professor Emerita at New York University, died on August 23 this year. Although spending much of her life commuting between Rome and New York, she lived in Cincinnati for 7 years. She was a UC Classics alumna receiving an M.A. in Classics from the University of Cincinnati in 1957. The title of her master’s thesis was An Endymion Sarcophagus from Ostia in the Metropolitan Museum (CLASS Stacks C.U. 152.57.W3). She also worked at the Cincinnati Art Museum for a number of years during a time when women were routinely discriminated against and living in the rather narrow-minded mid-west for a worldly European and New Yorker was not easy, so her years here were not always happy. She once told me that she had cried herself to sleep every night. I suspect that some of that may have been for my benefit when I complained about “close-minded and lazy” Cincinnatians. Professor Bonfante was always supportive. She understood empathy and unconditional friendship. While in Cincinnati she and her then husband were good friends with and mentors to Walter E. Langsam, the son of former president Walter C. Langsam, after whom the Langsam Library was named. UC Classics Professor Barbara Burrell was a student at NYU of both Professor Bonfante and her late second husband Leo Raditsa. In 2005, Professor Burrell invited Professor Bonfante to UC as a guest lecturer in a graduate class on Roman Archaeology at which she spoke on “The Etruscans as Mediators Between Classical Civilization and the Barbarians of Europe.” Professor Bonfante eventually left Cincinnati to return to New York where she had earned a B.A. in Fine Arts and Classics from Barnard College in 1954 and, eventually, after having a daughter, Alexandra, and later divorcing her first husband, a Ph.D. in Art History and Archaeology from Columbia University in 1966. The title of her doctoral dissertation was Etruscan Dress: Studies in Early Italian Art and Culture.

Larissa Bonfante was born on March 27, 1931, in Naples, Italy, but immigrated to the United States when she was only eight years old, at the beginning of WWII and at the height of Fascism in Italy, together with her mother and father, the linguist Giuliano Bonfante, Professor of Indo-European Linguistics at Princeton University, and her brother, journalist Jordan Bonfante. Professor Bonfante was a beloved teacher to many classics students at Barnard and later at New York University; her archaeology seminars at NYU were legendary. Not only was she a very knowledgeable and inspirational teacher, but she was also admired for her sense of humor and embrace of modernity. To her students she epitomized Terence’s homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto. As Professor Bert Smith introduced her when Bonfante gave the Haynes lecture at Oxford, “she has a restless intellect.” Her extensive (more than 200 peer-reviewed articles, a dozen books, many encyclopedia entries (Encyclopedia Britannica, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, Oxford Companion to Archaeology, World Book Encyclopedia, etc.), consultancy to the National Geographic, book reviews, book chapters, and conference talks, too many to count, and varied oeuvre in Italian, French, and English covered Etruscan culture and language, Roman history, and Ancient Greek literature and civilization. She was the founder of Etruscan News: Newsletter of the American Section of the Institute for Etruscan and Italic Studies, and in 2007 she received the Gold Medal for Distinguished Archaeological Achievement from the Archaeological Institute of America, the same honor now bestowed upon UC Classics Chair Jack Davis this year.

Much of her work in recent years was dedicated to examining the Etruscan exceptionalism in art and customs as reflected in frescoes, pottery, architecture, mirrors, funerary practices, language, family life, and influence on the Greeks, Romans, and the many neighbors in Europe and the Mediterranean with whom the Etruscans traded. She did not shy away from controversial subjects such as human sacrifice which she was convinced was a reality both in pre-Classical Greece and among the Etruscans. Her research interests included Late Antiquity and the relationship between pagan Roman Emperor Julian the Apostate and his admirer, the historian Ammianus Marcellinus, and she translated The Plays of Hrotswitha of Gandersheim (Bolchazy-Carducci 2013).

In her scholarship she made a number of new and transformative observations. Even though her “Gender Benders” article (in Edward Herring and Kathryn Lomas (Eds.). Gender Identities in Italy in the First Millennium BC. BAR International Series 1983, Archaeopress 2009, pp. 109-116) was written, as she said, “for fun,” and read out loud at one of the wonderfully collegial meetings of the Accordia Institute in London, it revealed the stereotypical and erroneous interpretations of figures in ancient art as male or female when in actual fact the true identities may be the reverse. Her book Etruscan Language from 1983 (Manchester and New York, revised in 2002), which she coauthored with her father, and The Barbarians of Europe: Realities and Interconnections (Cambridge 2011), have both been highly influential and greatly enhanced our understanding of the Etruscans and their language, which we can read although not entirely understand, and the many discussions of its origin, and the Barbarians challenged long held beliefs and misconceptions about those in the peripheries of the Greek and Roman worlds. Her introduction to the Barbarians, a book she edited, and for which she was the creative impetus, is one of the best introductions to the topic. Her not yet published book on Nudity as a Costume in the Ancient Mediterranean and her many articles on the subject altered our understanding of Greek nudity. She argued, based on Herodotus, that the Greeks used their innovation of male nudity along with the Greek language to distinguish themselves from “barbarians” and that in time male nudity became the mark of a Greek citizen, in particular in Athens and the mainland. Ionian kouroi were generally draped. She also made important observations about the Roman triumph in a series of articles as the central symbol of Roman military virtus. In contrast to the Greeks, who emphasized their distance from both contemporary barbarians and past ancestors, the antiquity of the triumph gave Rome its great prestige, and kept it from changing.

As prolific as her research about the Greeks, Etruscans and Romans were, she always felt that Latin literature was closest to her heart. It was this that she most enjoyed teaching and missed the most when she retired from teaching. “Teaching Lucretius,” she said, simply meant “sharing the wonders of his rugged rhythms and his images, both touchingly personal and magnificently cosmological” [personal communication]. “In the music of Horace,” she added, especially the poem about turning into a swan (Ode II. 20), she argued that “Horace is more open than usual about his personal feelings, about his fear of death and that accusations of its “grotesque” proved its effectiveness” [personal communication].

As is true for many scholars of her generation, she was a well-rounded classicist, i.e., she was equally at home in Greek and Latin philology as in ancient history, classical art and archaeology. She could discuss psycho-analysis (she was active in a NY group applying psycho-analytic methodology to classic literature) as easily as astrology. She once interpreted my horoscope. I was curious in spite of my disinclination towards anything religious or spiritual. However, her open-mindedness and “restless intellect” did not mean that she was not rigorous in her research, writing or teaching. When we students were not doing sufficiently well at reading Etruscan, she impatiently reprimanded us for being lazy and not applying ourselves. In our defense, it was our first class on the subject, but we all rushed to the library and hit the books. By the next session we were all quite proficient. When a visiting scholar gave a talk at NYU she criticized her “sloppy” research, methodology and findings in very strong terms. She could not abide by what she deemed to be careless reasoning by either colleagues or her students.

It is fairly easy to write about the teacher and scholar Larissa Bonfante. To speak about a close friend of 21 years I am not yet ready to do at length, maybe someday. Also, only a very cursory portrait can be painted in a blog post, but I cannot let this year end without saying something about this remarkable woman, scholar and friend.

My first encounter with Professor Bonfante’s embrace of all things human was when I and her other students were headed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to give class presentations (mine was on the Euphronios vase, which was still at the Met at that time) when by the Cooper Union Square subway station Professor Bonfante with open arms walked towards and hugged some scary-looking youths with tomahawk haircuts, nose rings, and tattoos. I was quite horrified at the company she seemingly kept. They turned out to be friends of her son, a DJ.

In spite of her social ease, she was a very private person in many ways. Much of what I learned about her earlier life was through references to things she remembered in conversation. She had many, many friends and mentees (and mentors) over the years. Her friendships were as varied as her academic interests. I was genuinely impressed when she introduced me to Walter Caporale, the President of Italian PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) and his now husband Carmine de Nuzzo, who was also her handyman in the neighborhood of Trastevere, Rome, where she kept two homes (after the death of her father). We all became good friends. I was also amused when she mentioned en passant that Rita Mae Brown of Rubyfruit Jungle fame, who was Professor Bonfante’s student of Latin at Barnard, had had a crush on her.

Once I left NYU for Princeton, our friendship truly blossomed. One of our regular outings was to the Metropolitan Museum (every new exhibition), followed by lunch at Candle 79 (in later years), and a stroll in Central Park. We visited numerous museums together both in the U.S. and Europe. A museum or exhibition visit with her was a treat. She was as interested in modern art as in classical; a futurist exhibition at MOMA could excite her as much as an artistic representation of classical mythology at Galleria Corsini. She was remarkably knowledgeable and noticed every detail in a work of art, which subsequently inspired and informed her research and writing.

Professor Larissa Bonfante in her “esse”. Here admiring the Chimaera at the National Archaeological Museum in Florence. She dismissed attempts at making the sculpture medieval as rubbish. She wrote extensively about this Etruscan masterpiece found at Arezzo. See for example, “Chimaera of Arezzo,” in An Encyclopedia of the History of Classical Archaeology, ed. by N.T. de Grummond (Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn. 1996) 159-160, 276-77.

Professor Bonfante on one of numerous visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Here in the Egyptian section.

Our favorite hangout in Rome was a café at Piazza di Trastevere, the location of Rome’s most beautiful and enigmatic church, Santa Maria in Trastevere, also the location of her father’s funeral ceremony. The café used to serve spremuta d’arancia in very tall glasses and with bread that I used to feed the many pigeons at the square. She always said that she was going to pretend not to know me when I tossed the bread to the birds and we laughed. She was a closeted pigeon fan, too.

Our favorite Roman hangout, a trattoria on Piazza di Trastevere. They served delicious spremute d’arancia and good bread, morsels for the square’s pigeons.

Our last big adventure was at Palazzo Pitti and the Boboli Gardens in Florence when she came to stay with me for a few days when I lived nearby on Via del Parione. Afterwards, she wrote in capital letters that no one seemed to understand when she said that she had “CLIMBED MT. EVEREST.” We had started out at Porta Romana and walked to the Porcelain Museum and Costume Gallery and Palazzo Pitti. We had not had breakfast, but the café in Palazzo Pitti was closed, so we set out to find another place to eat and followed directions to something called Das Kaffeehaus, which sounded promising, but was no longer a functioning coffee house, so we climbed even further to eventually end up at Forte di Belvedere. Our climb took hours. It was mid-August and the temperature was in the upper 90s. We were both exhausted, but Professor Bonfante had become dizzy. I was trying to find water for her. However, once we finally reached an actual and open café, she bounced back without difficulty. I had a harder time.

Professor Bonfante relaxing after a more than four-hour climb to Forte di Belvedere with a magnificent view of Florence, seemingly undeterred in spite of the mid-August pressing heat.

The spectacular view of Florence from Forte di Belvedere was perhaps worth the “climb to Mt. Everest.”

I wish we had known then that her lungs were besieged with cancer and not pneumonia with which her New York doctors had diagnosed her repeatedly. When she was finally correctly diagnosed, her lung cancer was at stage 4. I spoke with her as she was in a taxi on her way to her first and only chemo treatment. She was in fairly good spirits and happy to finally begin to combat her illness. We made plans for me to come to NY this week in December to go Christmas shopping as we had done many times before. When I spoke with her afterwards she was completely transformed. The doctors had said that she had looked 20 years younger and she did. She was extremely energetic and young at body and heart; after the treatment she said that she looked like a very old and frail woman and that the chemo had “destroyed” her. Her voice sounded small and unsteady; in her last email to me on August 16 she said that we “have something special, you and I” and in her last phone call a couple of days later she said that she was “proud of my career and proud to have been my teacher.” It was obvious that she knew that her death was near. On August 22, the day before she died, I told her on the phone how much I loved her. She was unable to speak at that point, but her daughter said that she had heard me. As I was on my way to chair a meeting at a conference in Athens, she passed away. I should have canceled my trip to Greece and gone to New York instead.

Her life, like most people’s lives, had challenges – burying both a husband and an ex-husband, the death of her mother and father (her father’s death at the age of more than 100 was particularly difficult for her) and of many friends and colleagues, one of her children’s battle with drug addiction and other issues. One of her many Bonfanteisms – “life is full of misery, occasionally punctuated by great tragedy”– oddly comforts me. However, she also led a charmed life in many ways. She was lauded and admired as a professor and scholar, a very popular lecturer at conferences all over the world. She was loved by many friends. In her last few hours she was surrounded by her daughter and son and brother. Her beloved cat Lola was already at a friend’s house.

Professor Bonfante introduced me to the cat sanctuary at Largo Argentina in Rome of which she was a great friend, helping the cats and their caretakers with monetary contributions as well as penning letters to the City of Rome that continuously threatens to close them down. She was also behind the popular standing feature of the Archaeocat in Etruscan News. Professor Bonfante had many cat companions over the years, ever since she was a girl in Princeton, New Jersey. Lola, seen here, became her last one.

I regret that future generations of scholars will not benefit from her willingness to edit their manuscripts, read their dissertation proposals and drafts, give them advice and remarkable support. She left many unfinished projects; with me her Selected Writings, and for Professor Bonfante perhaps most importantly, she did not get to finalize the publication of the Jerome Lectures which she had given at the American Academy in Rome a few years back and on which she had worked tirelessly. Her lectures were usually colloquia, ad lib. She rarely if ever read from a prepared manuscript, so to subsequently publish talks that she had given necessitated much work. Larissa Bonfante was a great scholar and a true Mensch. Her necrology to Professor Margarete Bieber, an admired teacher and mentor at Columbia, is beautifully written and from which I would like to quote a passage that could perfectly and equally apply to Professor Bonfante: “A visitor to her warm New York apartment emerged from a long, book-filled corridor into a bright sun-filled room, to face her expectant smile, offer of tea and chocolate cake, and conversation about mutual friends and plans…” (Bonfante, L. “Margarete Bieber,” Necrology in Gnomon 51 (1979) 621-624).

I am proud, and grateful, to have been Professor Bonfante’s student, but even more so to have been her friend.

A brief bibliography

1955 “Caere, Necropoli della Banditaccia,” Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 1955, 57 (excavation by the Istituto di Archaeologia dell’ Università di Roma, 1951);

1970 “Roman Triumphs and Etruscan Kings: The Changing Face of the Triumph,” Journal of Roman Studies 60 (1970) 49-66; 1971 “Etruscan Dress as Historical Source: Some Problems and Examples,” American Journal of Archaeology 75 (1971) 277-284, pls. 65-68.

1976 Editor, with Helga von Heintze, In Memoriam Otto J. Brendel. Essays in Archaeology and the Humanities (von Zabern Verlag, Mainz 1976).

1978 “The Arnoaldi Mirror, the Treviso Discs, and Etruscan Mirrors in Northern Italy,” American Journal of Archaeology 82 (1978) 235-238.

1979 The Plays of Hrotswitha of Gandersheim, with Alexandra Bonfante-Warren, 1979. Bolchazy-Carducci.

1979 “The Language of Dress: Etruscan Influences,” Archaeology 31 (1978) 14-26.

1980 “Historical Art: Etruscan and Early Roman,” American Journal of Ancient History 3 (1978) [1980] 136-162.

1981 Out of Etruria. Etruscan Influence North and South. British Archaeological Reports, International Series S103.

1983 (revised edition in 2002) The Etruscan Language: An Introduction, with G. Bonfante (Manchester and New York).

1984 “Human Sacrifice on an Etruscan Urn,” American Journal of Archaeology 88 (1984) 531-39.

1985 “Amber, Women, and Situla Art,” Journal of Baltic Studies 16 (1985) 276-291.

1986 Etruscan Life and Afterlife. A Handbook of Etruscan Studies, Detroit, MI.

1989 “Nudity as Costume in Classical Art,” American Journal of Archaeology 93 (1989) 543-570.

1989 “Wounded Souls: Etruscan Ghosts and Michelangelo’s ‘Slaves’,” with Nancy de Grummond, Analecta Romana Instituta Danici 18 (1989) 99-116.

1989 “Aggiornamento: il costume etrusco,” Atti, II Congresso Internazionale Etrusco, Firenze 1985 (Rome) 1373-1393, figs. 18 on 3 pls.

1990 Reading the Past: Etruscan. British Museum Publications. London and Berkeley, California.

1990 “Caligula the Etruscophile,” Liverpool Classical Monthly 15.7 July (1990) 98-100.

1992 “The Poet and The Swan: Horace Odes II 20,” Parola del Passato N.S. 47 (1992) 25-45.

1994 The World of Roman Dress (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press), co-editor, with Judith Lynne Sebesta

1996 “Etruscan Sexuality and Funerary Art,” in Sexuality in Ancient Art, ed. by N. Kampen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1996) 155-169.

1997 Etruscan Mirrors. CSE USA 3. New York. Metropolitan Museum of Art (L’Erma di Bretschneider, Rome)

1997 “Nursing Mothers in Classical Art,” in Naked Truths: Women, Sexuality and Gender in Classical Art and Archaeology, ed. by C. Lyons, A. Koloski-Ostrow (Routledge, New York, London) 174-196.

1998 “Livy and the Monuments.” In Boundaries of the Ancient Near East. Festschrift for Cyrus Gordon (Sheffield 1998), 480-492.

1998 Editor, G. Bonfante, The Origin of the Romance Languages (Winter Verlag, Heidelberg 1998).

2003 Etruscan Dress. Updated edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

2008 “Freud and the Psychoanalytical Meaning of the Baubo Gesture in Ancient Art.” Source: Notes in the History of Art 27, Nos. 2-3: 2-29.

2011 L. Bonfante, ed. The Barbarians of Europe. Realities and Interconnections. Cambridge.

2013 “Human Sacrifice. Etruscan Rituals for Death and for Life.” In Chiaramonte Trerè, C., Giovanna Bagnasco Gianni, Francesca Chiesa. 2013. Interpretando l’Antico. Scritti di archeologia offerti a Maria Bonghi Jovino. Università di Milano. Quaderni di Acme134. Milan, Cisalpino. Vol. 2, 67-82.

2013 “Women and Children.” In J.M Turfa, ed. The World of the Etruscans. Routledge, Chapter 20, 426-446.

2014 “Conversando con Francesca: sul tabú del sacrificio umano.” In Memory of Francesca Serra Ridgway. In M. D. Gentili, L. Maneschi, eds. Mediterranea, vol 11 (1914). Studi e ricerche a Tarquinia e in Etruria. Atti del simposio internazionale in ricordo di Francesca Romana Serra Ridgway. Tarquinia, 24-25 settembre 2010. Parte II.

2015 Co-editor, with Helen Nagy, Highlights of the Collection of Antiquities of the American Academy in Rome. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press.

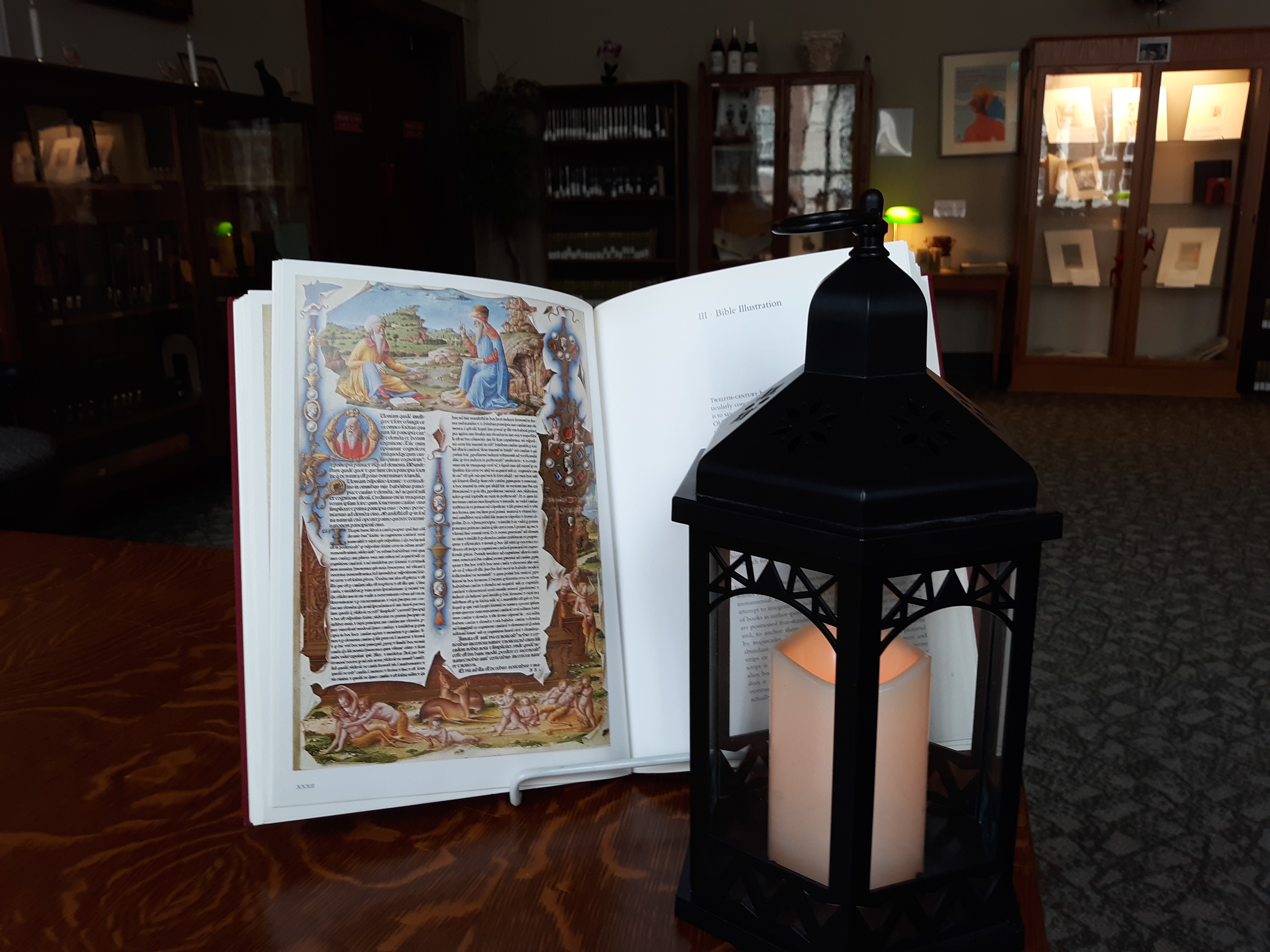

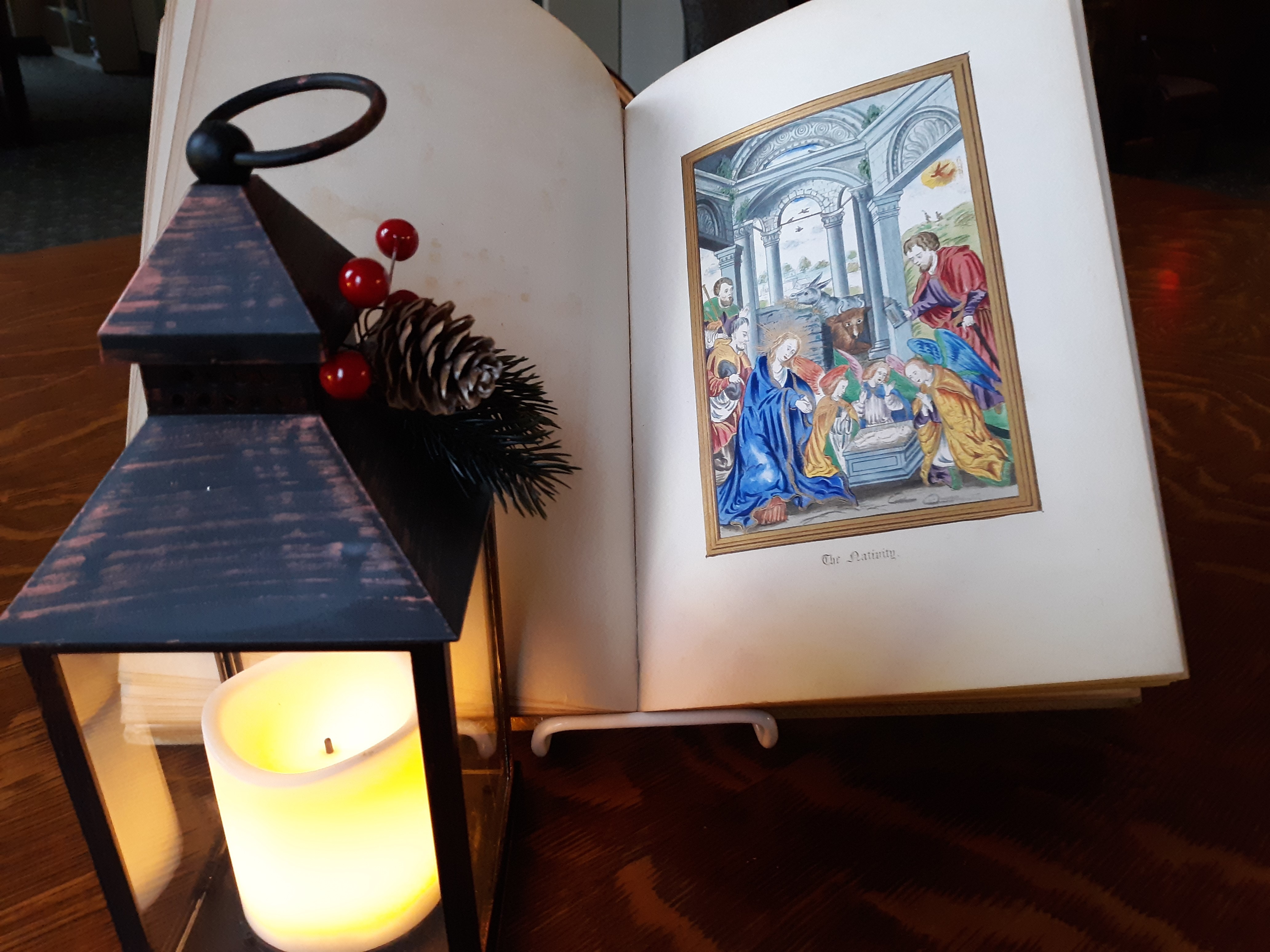

The faculty and staff of the University of Cincinnati Libraries bring you good tidings of the season and wish you a prosperous and joyful 2020! UC Libraries will be closed for Winter Seasonal Days, Dec. 23-Jan. 1, with the exception of the Donald C. Harrison Health Sciences Library, which will be open on a limited schedule. A complete list of library hours is available

The faculty and staff of the University of Cincinnati Libraries bring you good tidings of the season and wish you a prosperous and joyful 2020! UC Libraries will be closed for Winter Seasonal Days, Dec. 23-Jan. 1, with the exception of the Donald C. Harrison Health Sciences Library, which will be open on a limited schedule. A complete list of library hours is available